Exclusive The Guardian: Limassol accountant helped Russian oligarchs hide their wealth offshore – now the firm is under UK sanctions.

The invitation was for dinner and dancing, at a mansion on St George’s Hill, a gated estate in Surrey that has become an enclave for wealthy Russians. The Chelsea Football Club director Eugene Tenenbaum was celebrating his 45th birthday, in “disco attire”. On the flyer emailed to guests, an old photo showed a small boy standing barefoot, in front of what appears to be a pile of hay. The caption underneath read: “You’ve come a long way baby!”

Tenenbaum had plenty to celebrate – as a close associate of Roman Abramovich, he helped manage an empire that ranged from the oilfields of Siberia to the Premier League in England – and he wanted to thank those who had helped along that journey. Among the guests on that September night in 2009 was Demetris Ioannides. He had flown in from Cyprus, staying at Surrey’s four-star Oatlands Park hotel.

A chartered accountant who opened his own practice in 1988, Ioannides founded the Cyprus branch of the accounting group Deloitte. In 2005, he led a management buyout, setting up his own firm, MeritServus.

But Ioannides retained ties to the London-headquartered group. On his website, he claimed to be chairman emeritus of Deloitte in Cyprus, and to be a “preferred service provider”.

For his clients, he looked to Russia and beyond. “A Cyprus holding company provides the perfect gateway to the EU,” the MeritServus website explained, noting that “Cyprus has double tax treaties with over 40 countries including Russia, Ukraine, Iran and China”.

For the past two decades, Ioannides has been part of a circle of Cypriot lawyers, accountants and banks focused on bringing some of the biggest fortunes out of Russia and into Europe and beyond.

Last week, a year after western governments unleashed a barrage of financial embargos against Russia in retaliation for the invasion of Ukraine, the music stopped. The UK government added Ioannides and his firm to its sanctions list, alongside a prominent Cypriot lawyer, signalling growing concerns over what the Foreign Office calls “oligarch enablers” operating in the Mediterranean island state. The Bank of Cyprus, adopting the UK measures, froze the relevant accounts.

The sanctions came after the Guardian’s reporting of the Oligarch files, a cache of more than 300,000 documents from the archives of MeritServus and affiliated companies. Material from the files suggests the firm last year helped Abramovich hurriedly reshuffle the trusts he used to manage his wealth, raising questions about whether the reorganisation was designed to avoid asset freezes.

Lawyers acting for Ioannides and MeritServus said: “Our client has no involvement in any Abramovich family trusts.”

Abramovich has not responded to questions regarding the management of his finances by MeritServus.

Lawyers acting for Tenenbaum said he had a “professional and friendly relationship” with Ioannides “over many years”.

All three men are now subject to sanctions by the UK government.

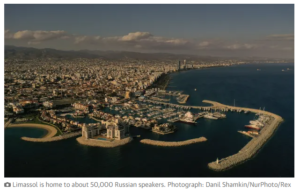

Some call it Moscow on the Med. Russian money accounted for more than €1bn held in Cypriot banks in 2021, and Russia is the most important single partner for inward and outward investment in Cyprus, according to the most recent data from its central bank. The second largest city, Limassol, is home to about 50,000 Russian speakers. When the country opened a “golden passports” scheme in 2013, to sell citizenship in return for investment, much of the €7bn raised came from Russian families.

“You can ask questions about whether Cyprus has been totally corrupted now by Russian capital. Russian money is so ingrained in Cyprus, so many of the elite have bought citizenship there,” says Timothy Ash, an associate fellow at the Chatham House thinktank.

“There’s an effort now to be more efficient, to follow through on political commitments to enforce these sanctions EU-wide”, says Dionis Cenusa, an associate of the Eastern Europe Studies Centre, a Lithuanian thinktank. “Cyprus’ Russian ties flew under the radar for a long time, it didn’t get the same focus from the EU Commission as companies working in Hungary, for instance. That’s shifted,” he adds.

The Oligarch files, which were shared with the Guardian by an anonymous third party, shine a light on the kind of services Cyprus offered Russia’s wealthiest citizens.

While MeritServus and its affiliates advise on tax and accounting, much of its work involves the creation and management of offshore companies and trusts. It handles the paperwork to set them up, provides directors for them, and even holds their shares. MeritServus is paid to provide a screen, a public face as shareholder and director of companies that really belong to its clients, so that the ultimate owners of valuable assets such as shareholdings, mansions and yachts can remain hidden from public view. Finservus, the company MeritServus used most often for this purpose, held shares in hundreds of companies on behalf of its clients.

The head office is a cream-coloured block in Limassol overlooking the district court. Here, Demetris works in the same building as his son and daughter, neither of whom are under sanctions as individuals. Panos Ioannides, a Yale graduate, is a director of MeritServus and specialises in investment schemes for those seeking Cypriot citizenship; Persella, who studied at the University of Bristol before taking an MBA at Columbia in New York, manages what appears to be an affiliated company, MeritKapital, a Cyprus investment firm with a London company that is licensed by the UK’s financial regulator.

Persella said in response to a request for comment:“MeritKapital Limited is a distinct and separate legal entity to the other “Merit” companies and it is run and operated by me, Persella Ioannides, not Demetris or Panos Ioannides.”

Separately, a spokesperson for Persella Ioannides said that MeritKapital had a “different client pool” to MeritServus.

Mr Blue

The staff at MeritServus had a codename for their biggest client, which often appeared in email exchanges. In a likely nod to the Chelsea team colours, they called Abramovich “Mr Blue”.

Records suggest the relationship began in 2001, the year Abramovich set up Millhouse Capital, which managed his stakes in companies ranging from oil and gas to aluminium and banking. Initially providing officers for Millhouse, over the next two decades MeritServus would help move the oligarch’s billions into European economies. Emails, banking records, loan agreements, company filings and trust documents record the purchase of trophy assets – property, art, football clubs, yachts and jets – alongside investments in startups and more established businesses. MeritServus was there when Abramovich bought Chelsea, it managed the trust that owns his former £150m home in Kensington Palace Gardens, and another that holds an $800m art collection.

It did not just handle transactions for Abramovich. The material seen by the Guardian suggests MeritServus undertook work for his associates, including Tenenbaum. And it acted for Russian businessmen unrelated to their affairs.

One of them was Konstantin Malofeyev, known as “the Orthodox oligarch” for his links to Russia’s state church system. He appears to have become a client from 2005, the year he set up his private equity group Marshall Capital Partners. A banker turned propagandist, Maloveyev was placed under sanctions by the EU and the US in 2014, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea. The Americans described him as “one of the main sources of financing for Russians promoting separatism in Crimea”. MeritServus appears to have kept him as a client until May 2017, carrying out a number of transactions involving millions of dollars and euros in 2015 and 2016, while he was under sanctions, in an apparent breach of Cypriot criminal law.

MeritServus says it had “inadvertently not identified” Malofeyev as being on the sanctions list. As soon as it became aware of its error, in 2017, the firm says it informed the accountancy regulator and the government department responsible for combating money laundering, and “the position was resolved” with both bodies.

Prior to being placed under UK sanctions, MeritServus also said it carried out normal services with proper permissions from regulators.

A long history

The ties between Cyprus and Russia are more than just commercial. They stretch back over centuries, with shared roots in their alphabets and religious bonds forged within the Orthodox Church. After independence from the UK in 1960, the USSR was quick to set up diplomatic links with the newly established Republic of Cyprus.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, the ties only deepened. Support from Russia came in the form of arms deals that heightened the long-running tensions between the Republic of Cyprus and Turkey. In 1998, a double taxation treaty between the two countries took the relationship to a new level.

By routeing their cash through corporate structures spanning Cyprus and other tax havens such as the British Virgin Islands, the businessmen who made their fortunes in the chaotic privatisations of the 1990s could slash their tax bills and avoid public scrutiny of their financial affairs.

In October 2010, Russia’s then president Dmitry Medvedev acknowledged the importance of the relationship during an official visit to Cyprus: “We have very good relations, we have a mutual understanding on nearly all international issues, we have a shared history, we have spiritual kinship, and we have the present day.”

It was around this time that annual Russian capital flows through the Mediterranean island began to reach into the billions. They peaked at over €21bn in 2012, according to the rating agency Moody’s, when it was estimated a third of all deposits were of Russian origin. A banking crisis, triggered by Greece’s national debt debacle, led to those sums reducing very significantly in the years that followed.

Some of the billions that flowed through Cyprus belonged to Abramovich.

Dig back through the oligarch’s long history of court disputes in London, and it is in a 2008 high court ruling that his relationship with Ioannides first emerges. The judge, who appears to have been somewhat bewildered by the complexity of the offshore arrangements used by the oligarch, described what he had found during the course of the hearings.

“The upshot is that there appears to be a web of companies, largely in the BVI and Cyprus, which hold various interests, personal and business, some very sizeable, of which Mr Abramovich is, or would appear to be, the ultimate owner. The Cypriot companies are ultimately owned, so far as the legal title is concerned, by Deloittes or Mr Demetris Ioannides, who was a director of Meritservus Ltd and Meritservus (Trustees) Ltd, two Deloitte Cypriot service companies, or by other Meritservus personnel.”

After a request for comment from the Guardian, Deloitte asked MeritServus to “cease and desist” from claiming any links or using the Deloitte name in its publicity. MeritServus has since changed the language on its website, removing the description of Ioannides as chairman emeritus of Deloitte Cyprus. An advertorial from the website of a Cypriot business publication that described MeritServus as an “offshoot” of Deloitte was also taken down.

With its bank accounts frozen and its operations now under UK sanctions, the future for MeritServus is unclear. Cyprus itself is faced with a difficult choice: turn away from Russia, or wait patiently for a resolution to the conflict in Ukraine.

This article was amended on 20 April 2023. An earlier version said Eugene Tenenbaum was celebrating his 50th birthday at the 2009 party in Surrey; in fact it was his 45th birthday.

Additional reporting by Rob Davies and Harry Davies