Countries in Scandinavia, a current security hot spot, are more visibly cracking down on citizens involved in Russian espionage, reports Politico.

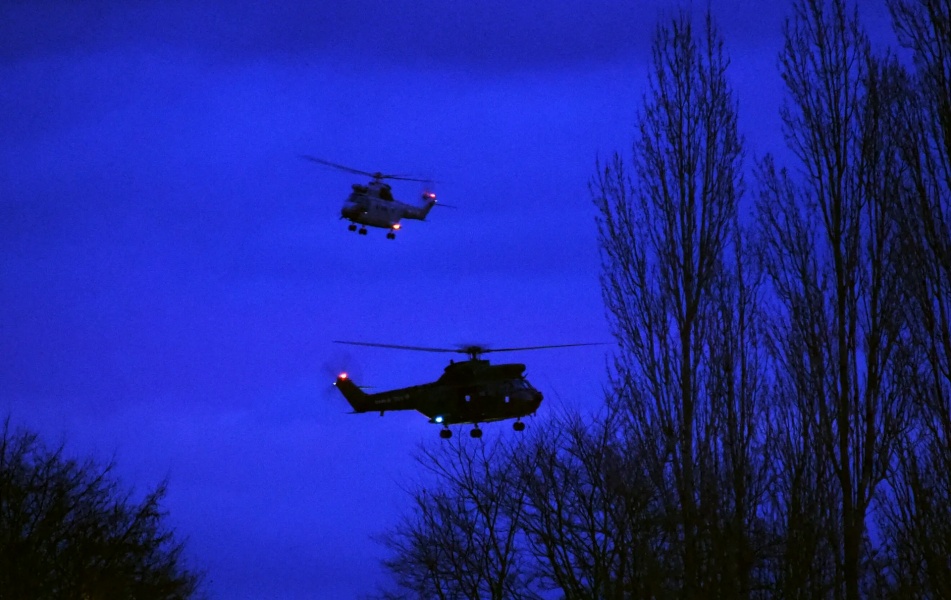

STOCKHOLM — Two military helicopters shattered the calm of suburban Stockholm on a late November morning, swooping over a private home in the sleepy locale of Kil in a high-profile raid on a Swedish couple accused of spying for Russia.

“I couldn’t believe it when I saw the police piling into their house,” a neighbor of the arrested Stockholm couple told POLITICO. “The noise of the helicopters woke up the whole street, and we just stood on our driveways watching the action.”

The rattle of helicopters in the darkness was the latest sign that European nations’ high-stakes games of espionage with Russia are increasingly being played in the open.

The raid netted a couple in their late 50s who now stand accused of slipping confidential commercial information to the Russian military intelligence agency GRU. They deny the accusations.

That same week, a closely watched court case began in Stockholm involving two brothers accused of passing official secrets from Swedish security agencies to the GRU; accusations they also deny.

Both cases have grabbed national headlines and shaken up Swedish citizens.

In another jaw-dropping takedown, this time in neighboring Norway, a man now believed to be a GRU officer was recently arrested on his way to a college where he had been operating under a false identity as a Brazilian academic.

And in the Netherlands, a deep-cover Russian operator was also recently exposed, with national news outlets similarly pouncing on details of the exposé.

All these cases point toward a shift in the way European states are handling counterintelligence operations: less sweeping of cases under the carpet and more splashy disruption and prosecution, experts observe.

The aim seems to be warning European citizens of the threats they face while simultaneously calling out Moscow, making it harder for Russian President Vladimir Putin to deny the actions of his intelligence agencies as the brutal invasion of Ukraine enters its 10th month.

“Europe is finished with subtle signals toward Russia,” said Carolina Angelis, a former analyst with the Swedish intelligence service who later founded a security advisory firm.

Estonia leading the way on convictions

A recent report by researchers at Sweden’s Defense Research Agency examining legal cases around state-backed espionage in Europe over the decade to 2021 found that the three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania accounted for nearly two-thirds of convictions. Estonia alone was responsible for half of the total.

According to the researchers’ assessment, this had little to do with Baltic states being intelligence targets. Rather, it’s a clear indication of their desire to demonstrate how genuine the espionage threat is (primarily from Russia but also to a lesser extent China), while at the same time demonstrating their ability to catch and convict spies.

High-profile Estonian prosecutions include that of Estonian soldier Deniss Metsavas,& who was named and called out as a traitor by the head of the Baltic state’s defense forces at a press conference in 2018.

Over the decade covered by the Swedish report, Russia in particular appears to be more aggressively spying on its European neighbors. According to Michael Jonsson, one of the report’s writers, this has fueled a debate among targeted states as to how overtly they should tackle Moscow’s espionage attempts.

The concept of a more visible counterintelligence strategy has begun to gain ground, Jonsson believes. The recent arrests in Norway and Sweden — as well as the conviction of a Swedish consultant for spying for the Russians in 2021 — are best seen in that context, he added.

Add to the equation how Scandinavia is currently a security hot spot: Sweden and Finland are on the lookout for attempts to monitor or derail the two countries’ accession to NATO, while Norway is particularly concerned about the integrity of its oil and gas infrastructure after the recent sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines under the Baltic Sea.

Also in Norway, a series of trials are now underway of Russians accused of flying camera-equipped drones over the Nordic country in contravention of a Norwegian law specifically banning Russians from doing so.

“Our interpretation is that gradually more European security services have concluded that the ‘Estonian approach’ is the way to go,” Jonsson said.

When cloak-and-dagger becomes public theater

The three recent cases of alleged spying in Sweden have included some colorful details.

The 47-year-old Swedish consultant was detained in 2020 after handing over commercial secrets from carmaker Volvo and truck-maker Scania to a GRU officer in a restaurant in central Stockholm. In Sweden, the identities of suspects are withheld to protect their privacy.

Pictures of the handover, where the agent received an envelope of cash, were splashed across local media — prompting the GRU officer, who had diplomatic immunity, to quietly leave Sweden soon after. The agent was sentenced to three years in prison in late 2021.

While such a situation was considered a rarity at the time, the subsequent hearing of two brothers accused of espionage relatively soon thereafter may be changing this perception.

The brothers’ trial, which began on November 25 and is expected to end later this month, centers on accusations that the older brother stole files from his employers, two Swedish intelligence agencies, to give to his younger brother — who in turn passed them on to the GRU in exchange for cash.

Documents released ahead of the trial detail how police observed the younger brother dumping a hard drive in a public trash can after his sibling was arrested, and how investigators combed through the elder brother’s deposit boxes at a local bank looking for evidence.

The recent raid of the suburban house on the edge of Stockholm could also end with a widely watched trial.

The detained man, a Russian who moved to Sweden in the 1990s and took Swedish citizenship, remains in custody, while his wife, also a Russian who adopted Swedish nationality, has been released. Police point out that she remains a suspect in the case.

“This is an extensive investigation which will continue for quite a long time,” Swedish public prosecutor Henrik Olin told reporters.

At the home of the suspects — a large, newly-built detached house — fresh snow has filled in the footprints of the police who charged up the driveway not long ago. Windows the police had broken as they entered had been sealed over with plastic sheets.

The neighbor said she’d always found the couple to be very pleasant, even if they seemed to want to keep to themselves.

“They were very courteous, we never suspected anything,” she said.

“But then, maybe that’s kind of the idea.”