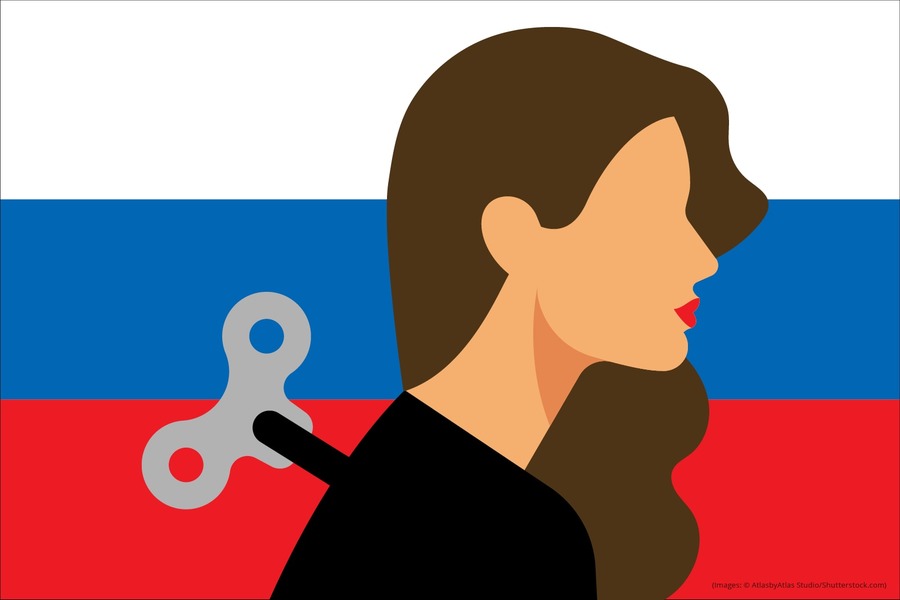

The Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security has analysed how Russian narratives about Ukraine are reproduced in European and North American online media through the use of toxic vocabulary, the choice of information sources, and analysis of common narratives.

The main trends were found during the monitoring held by the Ukrainian social startup LetsData in partnership with Detector Media NGO between July 1 and 14. Publications containing references to Ukraine or Russia’s war against Ukraine are collected in real time in the original language and processed with the help of artificial intelligence components.

Not just Russia Today: pro-Kremlin media as a source of information in Europe and North America. Despite attempts to block pro-Kremlin media in the West, some online media in Europe and North America are still using Russian propaganda publications (such as TASS or RIA Novosti) as sources of information in journalistic materials. This, by the way, is one of the ways for Russian narratives to enter the Western information space.

In general, among the studied countries, pro-Kremlin media are not cited frequently, but it does occur. Pro-Kremlin media citations were most frequently used by Latvia and Lithuania (8.6%), Austria (5.7%), as well as Germany (4.2%) and Canada (4.2%).

Among the pro-Kremlin media, RIA Novosti, TASS and Sputnik are cited most often. Only a small percentage of references to Izvestia have been found in France, Germany, the USA, Lithuania and Latvia. RT also has rather few mentions in the Western information space, among the minuscule percentages of citations the highest figures can be found in Poland (11.7%) and Mexico (10.9%).

Kremlin terminology and incorrect transliteration of Ukrainian toponyms in the Western media

The highest overall percentage of publications about Ukraine containing toxic language was found in the online media of France (33.2%) and Portugal (29.1%). Toxic vocabulary primarily refers to the use of Kremlin terminology to denote the war against Ukraine (such as “special military operation”) and the transliteration of the names of Ukrainian cities from the Russian language.

The online media of European countries infrequently use Kremlin terminology referring to Russia’s war against Ukraine, such as “special military operation” (no more than 2% of all publications about Ukraine in each of the countries studied) or “the Ukrainian crisis” (up to 1.7%); only the term “conflict” is used more frequently (the highest percentage was found in Portugal — 11.1%, in other countries, it stays under 7.2%). Instead, incorrect transliteration of Ukrainian toponyms through the medium of the Russian language is much more common.

The situation is opposite in the information space of North American countries. For instance, in Canada, 8.9% accounts for the use of the term “conflict” and another 8.4% — “special military operation”; on the other hand, the incorrect transliteration of Ukrainian toponyms does not exceed 0.8%. Mexican online media also frequently use the term “conflict” (9.8%); however, all other examples of toxic vocabulary, other than the wrong transliteration of Kyiv (5.5%), do not exceed 0.7%. One of the reasons for the appearance of such terminology or incorrect transliteration may also be the quoting of pro-Kremlin media and their use as sources of information.

What attitudes and narratives are disseminated through the online media of European and North American countries? In general, the issue of Ukraine is covered more actively in Europe than in the countries of North America. For example, among the topics that appear in the context of Ukraine, the topic of economy is the most common both in European countries and among North American countries. However, the number of publications in the period from July 1 to 14 in Europe was almost 15,500, and in the countries of North America — 4,500.

The online media of European countries infrequently use Kremlin terminology referring to Russia’s war against Ukraine, such as “special military operation” (no more than 2% of all publications about Ukraine in each of the countries studied) or “the Ukrainian crisis” (up to 1.7%); only the term “conflict” is used more frequently (the highest percentage was found in Portugal — 11.1%, in other countries, it stays under 7.2%). Instead, incorrect transliteration of Ukrainian toponyms through the medium of the Russian language is much more common.

The situation is opposite in the information space of North American countries. For instance, in Canada, 8.9% accounts for the use of the term “conflict” and another 8.4% — “special military operation”; on the other hand, the incorrect transliteration of Ukrainian toponyms does not exceed 0.8%. Mexican online media also frequently use the term “conflict” (9.8%); however, all other examples of toxic vocabulary, other than the wrong transliteration of Kyiv (5.5%), do not exceed 0.7%.

One of the reasons for the appearance of such terminology or incorrect transliteration may also be the quoting of pro-Kremlin media and their use as sources of information.

Other than the topic of the economy, coverage of other issues varies between continents. In particular, the online media of European countries focus more on the topics of European integration of Ukraine in terms of the number of publications. However, in the countries of North America, the topic of European integration is covered less often, with this topic, sanctions, and the food crisis being almost at the same level.

The percentage of publications on military aid is rather insignificant both in European countries and among the countries of North America.

By the way, a similar trend was observed in European countries between July 18 and 31 based on the monitoring by Ukraine War Disinfo Working Group, which studies the media landscape of Eastern and Central European Countries for presence of Russian narratives. Pro-Kremlin narratives on military aid were not observed in Bulgaria and Latvia between July 18 and 24, and also in Georgia, Slovakia and the Russian-language segment of the Baltic States between July 25 and 31. During this period, other topics prevailed in the named countries, such as sanctions and the course of the war in Ukraine.

According to the infographic, we can see that in the countries of Europe and North America, the identified narratives have a positive, neutral or negative tone. We will take a closer look at toxic narratives that reproduce Russian narratives.

Europe. In the online media of European countries, “suggestions of peace talks” are gaining popularity. The discourse about dialogue and diplomacy as the only tools for solving war is present in almost every country. For example, in Hungary, Germany and Austria, this discourse is dominant. A narrative about the negative consequences of sanctions for European countries and the United States is also widespread.

The highest number of pro-Russian narratives could be found in the Hungarian online media. Some of them are based on the statements of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, for example, that “Hungary does not believe in the policy of sanctions; peace talks are necessary.”

Previously, while researching the dissemination of anti-sanction narratives in pro-Russian channels of 11 European countries between June 13 and August 7, we already observed the trend in Hungary when pro-Kremlin narratives entered the country’s information space due to the statements made by Hungarian officials. For example, Prime Minister Orbán regularly makes statements against sanctions, which are picked up and broadcast by pro-Russian messengers throughout the region.

North America. In the countries of North America, in particular in the USA, the toxic narratives emphasise on the negative consequences of sanctions for Europe and the USA, alongside a tendency towards peace negotiations.

In Canada, toxic narratives are primarily reflected in the statements of Russia’s representatives (Vladimir Putin, Russian ambassador in the UK, the Kremlin). This clearly confirms the assumptions about the aforementioned ways in which toxic vocabulary enters the information space, particularly in Canada. Among the topics, mostly anti-sanction messages from the Kremlin were found.

Such excessive citing not only of pro-Kremlin media but also of Russia’s representatives themselves becomes a source of Russian narratives in the Western information space, too. The Kremlin’s rhetoric is based on emotionality and intimidation, and accordingly, such messages are immediately picked up and carried in the Western media, and along with these quotes, the Russian narratives themselves also end up there. For example, we have already studied the media landscape of Polish media, where we found that one of the main reasons for citing Russia’s representatives in the Polish media environment is their intimidating statements. For example, Dmitry Medvedev was cited more, despite his generally low popularity in the Polish online media, in the context of his threats with “World War III” against Lithuania for blocking the transit into Kaliningrad region.

Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security

Articles on topic:

Cannibalism, a New Theme for Russian Propaganda

Russian propaganda sets a new direction for another info attacks