In 2014, two senior officials of one of the biggest banks in Cyprus, RCB Ltd., visited Constantinos Petrides, a top aide to the country’s president. They weren’t there to talk banking. Instead, according to a Cyprus government investigation, the officials pressed Petrides to approve the citizenship application of a Russian national he said was under sanction by the European Union.

Petrides balked, and the meeting got heated.

“One of them almost accused me of being a traitor and harming relations between Cyprus and Russia because I didn’t want to naturalize a person,” Petrides told the investigators.

The report, obtained by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), didn’t name the Russian national or say what happened to the application or why it was important to the RCB officials. However, the application was part of the now-discredited “golden visa” program, which granted European Union citizenship to 2,869 Russian nationals and would ultimately generate about $7 billion for the tiny island nation, swelling deposits of RCB and other major Cyprus banks before blossoming into a major European scandal.

RCB, its managers and shareholders had long-standing ties to the Kremlin. Indeed, Russian President Vladimir Putin himself once — mistakenly — referred to RCB as a “subsidiary” of Kremlin-controlled Vneshtorgbank, known as VTB, which at the time was just a major shareholder. For Cyprus, these connections were hardly unusual: A Russian oligarch has long been a major shareholder of the country’s top bank, the Bank of Cyprus, and from 2013 to 2015 its board’s vice chairman was one of Putin’s former Leningrad KGB colleagues. Three of the top four banks were soon to be implicated in Kremlin-linked money-laundering scandals.

The big banks had an even more important credential, though, one that wired them directly into the Western financial world: They were all licensed — and directly supervised — by the European Central Bank, the powerful banking authority based in Frankfurt, Germany, that controls the eurozone.

For years, RCB, formerly known as Russian Commercial Bank, had been among the ECB’s “systemically significant banks,” a status that, analysts say, helped it to expand its customer base in Cyprus. Then, in February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. A month later, the ECB’s Banking Supervision division announced “decisions” to help unwind RCB, which, despite “abundant” liquidity and capital, had suddenly decided to get out of the banking business.

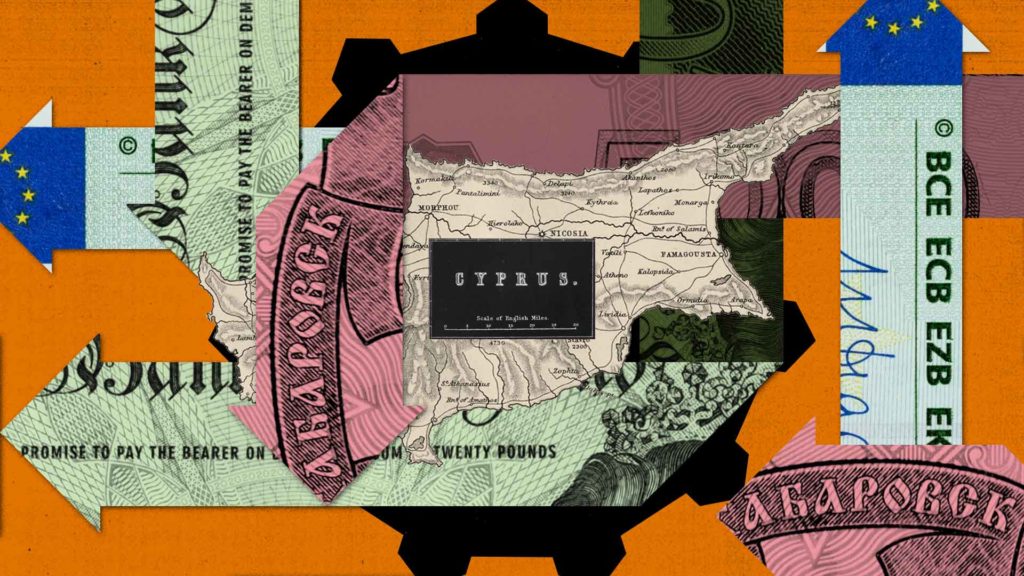

But RCB was only one cog in what became known as the “Cyprus model,” a giant conveyor belt for Russian wealth to the West located in an EU member state, its banking system overseen by the ECB. As of 2020, according to the Center for the Study of Democracy in Sofia, Bulgaria, Russians had “invested” more than $200 billion in Cyprus, fully half of Russia’s investment in Europe and more than in Germany, the U.K., Spain, Switzerland and Austria combined. And on paper, at least, the island of 1.3 million people was one of the world’s biggest investors in Russia. At one point, roughly 300 Russian-owned companies were worth 80 percent of the wealth of Cyprus, which is known as “Moscow on the Mediterranean.”

The Russian money flow was a bonanza for Cyprus’ powerful industry of bankers, offshore service providers, accounting firms like PwC and other Big Four firms, and an army of 4,000 lawyers — all deeply intertwined with a Cypriot political class that erected some of Europe’s most stringent corporate secrecy rules and turned the Central Bank of Cyprus into a protector of the system rather than its regulator.

How intertwined? From 2013 until this year, the founder of a major offshore service provider, Nicos Anastasiades, served as president of Cyprus. A 2019 OCCRP investigation found that his law firm’s partners served as officials of shell companies linked to massive suspected money-laundering operations, including deals linked to Putin allies that took place before Anastasiades took office. (OCCRP said its documents did not contain any specific evidence that the firm or that firm employees broke any laws or committed any crimes. In a statement to ICIJ, the firm says, “We categorically would like to state that none of the members of our law firm have been implicated in any wrongdoing. These allegations are entirely unfounded and lack merit.” The firm added that in the wake of the OCCRP report, Cyprus’ anti-money laundering agency conducted a “comprehensive investigation, which involved a meticulous examination and analysis of the data presented to them” and issued a 2019 report “fully exonerating our firm and confirming that there were no indications of any involvement in illegal or suspicious activities.” As part of a seven-page letter to ICIJ, Anastasiades said he has had “absolutely no active involvement” in the firm since 1997 and transferred all his shares to his two daughters upon taking office in 2013. He also noted that the firm’s offices are in Limassol, while the headquarters of the political party he headed is in Nicosia.)

Russian President Vladimir Putin with the former president of Cyprus, Nicos Anastasiades, in 2019.

Russian President Vladimir Putin with the former president of Cyprus, Nicos Anastasiades, in 2019.

Analysts describe the Cyprus model as the beating heart of the Putin regime’s financial circulatory system, pumping Russian assets either to be stored in the West as financial assets, yachts or luxury real estate, reinvested back into ever-expanding control of the Russian economy, or stockpiled to undermine and corrupt democratic institutions in the West.

Even as the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and its media partners report new revelations detailing how the Cyprus model helped to finance the Putin regime, one inescapable fact remains: The model metastasized within the EU itself, with Cyprus’ major banks directly supervised by the powerful ECB. How this happened is clear now. What is less clear is why it was ever allowed to happen in plain sight.

A new dominance

The alliance between Russia and Cyprus dates back centuries, based on a common Orthodox Christian religion and, during the Soviet era, close ties between their communist parties and active educational and cultural exchange programs that further knit the communities together. In the 1950s, the Soviet Union pushed for Cypriot independence from British colonial rule over opposition from Washington. After Cyprus achieved independence in 1960, the Kremlin provided political cover when, three years later, Cypriot Greek politicians broke a power-sharing agreement with the island’s Turkish community, centralizing power in the executive branch.

Turkey’s 1974 invasion and occupation of the island’s north region displaced 200,000 people, most of them Greek Cypriots, sparking global condemnation; the Kremlin exploited Cyprus’ national trauma to drive a wedge between two NATO members, Greece and Turkey. Since the 1980s, Russia and Cyprus have signed more than 50 treaties, protocols and memoranda of understanding. When the Soviet Union dissolved in December 1991, Cyprus was among the few countries to which Russians could travel without a visa.

Cyprus, with a cosmopolitan atmosphere set amid an idyllic Mediterranean landscape, was both an accessible and attractive destination for Russian wealth during the turbulent post-Soviet transition. As Russian money poured into Cyprus’ banks, a rising industry of Cypriot lawyers, bankers, accounting firms like PwC, tax planners, and investment managers rose to process it — helped by lax bank regulation that asked few questions about where the money came from and notorious secrecy laws that blocked foreign authorities (or anyone) from learning the real owners of Cyprus-registered corporations and account holders.

By the time Cyprus ascended to EU membership in 2004, Russian economic dominance already reigned over the island, and the “golden visa” program supercharged it. Launched in 2007 and expanded in 2013, it would ignite a real estate and lending boom and generate big fees for law firms, including the one founded by Anastasiades, bloating the banking system.

“Cyprus basically closed its eyes to billions [of dollars] of deposits of murky origins,” Martin Vladimirov, an analyst with the Center for the Study of Democracy, told ICIJ, citing neutered enforcement as key to the model. “You had all the rules in the world, but for the big [clients] you strike a deal with the manager of the bank — and they know that.”

And so they did. By 2012, the Cyprus banking system would swell to 400 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, among the highest in the world.

Kremlin control

In January 2013, German Chancellor Angela Merkel traveled to Limassol, Cyprus, to attend a meeting of the European People’s Party, the business-friendly, center-right coalition that usually commands a leading share of the European Parliament. There she shook hands with Anastasiades, another EPP leader who was then ahead in the polls to become Cyprus’ next president. The handshake symbolized a powerful political alignment; both countries actively promoted trade with Russia.

Then-president Nicos Anastasiades greets German Chancellor Angela Merkel prior to the extraordinary European People’s Party summit in Limassol, Cyprus, on Jan. 11, 2013.

Then-president Nicos Anastasiades greets German Chancellor Angela Merkel prior to the extraordinary European People’s Party summit in Limassol, Cyprus, on Jan. 11, 2013.

The meeting came at a perilous moment for Cyprus — and for Europe. The financial crisis roiling Greece and other eurozone countries had washed up on Cyprus’ fragile banks, bloated with Greek bonds and bad real estate loans. Massive bank losses threatened to bankrupt the country, forcing Cyprus to apply for financial assistance from the ECB; the European Commission, the EU’s executive body; and the International Monetary Fund — known as the troika.

But there was a problem: Not only were Cyprus banks considered reckless and poorly supervised, they were stuffed with Russian money — $31 billion, a figure larger than Cyprus’ GDP. Much of that was held by nonresidents, and much of it believed to be dirty. As Europe’s dominant economic power, Germany would be responsible for the lion’s share of any bailout decision.

Two months before the Cyprus meeting, “EU Aid for Cyprus a Political Minefield for Merkel” declared a Der Spiegel headline, adding the subhead: “Bailing Out Oligarchs.” The story featured a leaked report from the German foreign intelligence service suggesting the main beneficiaries from a eurozone bailout of Cyprus would be Russian oligarchs, businessmen and mafiosi.

Revelations that Cyprus bank regulators and law enforcement had been running interference for the Kremlin added to the pressure. In one case, regulators refused to investigate a $230 million Russian tax fraud, a large share of which had been laundered through Cyprus banks. Known as the Magnitsky Scandal, after Sergei Magnitsky — the Moscow-based lawyer for an American investment firm who was beaten to death in a Russian prison after exposing the fraud — the case had become a global cause celebre and fueled passage the previous year of the landmark U.S. anti-corruption law called the Magnitsky Act.

“Sergei Magnitsky uncovered Russia-to-Cyprus money laundering, and look what happened to him,” Canada’s Financial Post said in a March 2013 headline.

Bill Browder, the anti-corruption activist who runs Hermitage Capital Management, the American firm that hired Magnitsky, launched a publicity campaign to demand that any bailout package for Cyprus include a probe of the Magnitsky fraud and cleaning up the country’s money-laundering oversight.

“I screamed bloody murder all over Europe,” Browder recalled in an interview with ICIJ.

Reform, though, was a long way off. An initial austerity plan, which would have affected small depositors but also involved big concessions for RCB, was rejected by Cyprus’ parliament. The rejection came amid intense pressure from Moscow, according to the former speaker of the parliament.

“The highest Russian leadership ensured it conveyed the message that if we touched RCB, we would have seen a reaction we had never seen before,” the former speaker, Marios Garoyian, said in 2014, according to a Cyprus Mail story a year later. “It was a crystal clear message to all of us.”

I screamed bloody murder all over Europe.

— Bill Browder, the anti-corruption activist who runs Hermitage Capital Management

In the end, the newly elected Anastasiades government accepted a $13 billion troika-imposed package that, to decrease costs to governments, confiscated big deposits and turned them into stock. One result of the so-called bail-in: Big Russian depositors were transformed into some of the largest shareholders of Cyprus’ biggest bank.

And instead of reform, the Anastasiades government moved to assert political control over the Central Bank of Cyprus, the country’s main bank regulator and anti-money laundering authority. The government started with a series of political attacks on the CBC’s governor, Panicos Demetriades, a U.K. economics professor appointed by the previous government. It then followed with legislation to assert management control over the central bank itself, shifting power over bank licenses and other critical tasks from the governor to two government-appointed board members. Unusually, these new “executive directors” were handed management authority alongside the governor. Demetriades coined a term for the new officials: “commissars.”

Cyrpus’ Panicos Demetriades became a target of the newly-elected Anastasiades government while he was governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus.

Cyrpus’ Panicos Demetriades became a target of the newly-elected Anastasiades government while he was governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus.

The changes sowed confusion among staffers, several of whom showed up in Demetriades’s office in tears, he told ICIJ. “The staff was scared of [the new board members],” Demetriades says. “They didn’t know who they were reporting to.”

The legislation flouted the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which created the EU and enshrined central bank independence as a key obligation of members. Mario Draghi, the ECB’s president at the time, wrote a letter protesting government attacks on Demetriades and demanding that the European Commission take “all action necessary” to force Cyprus to protect the independence of its central bank.

“This raises serious concerns about the protection of the personal independence of Mr. Demetriades, not only as the Governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus, but also as a member of the Governing Council of the ECB,” Draghi wrote. The ECB fired off angry legal opinions.

Meanwhile, the Cyprus attorney-general opened an investigation into Demetriades following the leak of confidential documents about alleged irregularities in a central bank contract with a major Wall Street restructuring firm, Alvarez & Marsal, to manage the financial crisis. Known as A&M, Alvarez & Marsal had played a lead role in resolving the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy during the 2008 financial crisis. The Cyprus contract included an extra “recapitalization,” or success, fee of €11 million and wasn’t presented to the central bank’s board, reports said. No charges were brought.

The Anastasiades-backed legislation passed. The European Commission didn’t act. Pressure on the Cyprus central bank came to a boil.

The Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

The Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

The floodgates open

By September 2013, the Bank of Cyprus’ Russian-oligarch depositors had transformed into major shareholders, and the bank was set to elect a new board. Government attacks on Demetriades had reached a fever pitch. With the economy having crashed and demonstrations in the streets, Demetriades was the target of death threats, scathing media coverage and near-daily calls from the parliament for his ouster.

That’s when Demetriades got a phone call from Anastasiades.

In his 2017 memoir, Demetriades writes that the conversation started amicably, then the president pressured him about the impending Bank of Cyprus board election. Anastasiades wanted the governor to approve his preferred slate of candidates, which included a vice chairman who worked with Putin in the Leningrad KGB and five other Russians.

“I hope you won’t turn down the candidates put forward,” Anastasiades said, according to Demetriades.

The banker demurred, enraging the president. “Watch it, because I will make public statements about you!” the president fumed, according to the central banker. “I will not stop. No one wins against me.”

In the end, the bail-in had inadvertently shifted power to the new Russian shareholders.

“We can laugh now, but it was meant to be a serious attempt to get the Russians out,” says Demetriades. “And in the end, they gave them the bank.”

Demetriades resigned in March 2014. The next month, Russia invaded and began its annexation of Crimea, sparking global protests and a wave of U.S. and EU sanctions against Russian institutions.

We can laugh now, but it was meant to be a serious attempt to get the Russians out. And in the end, they gave them the bank.

— Panicos Demetriades, former governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus

In his letter to ICIJ, Anastasiades said the main rise in Russian financial influence occurred before 2010 and that his administration oversaw a dramatic decline in deposits held by Russian businessmen and individuals, from a peak of 40% in 2013, to 2.2% by the end of 2022; the suspension of more than 43,000 shell companies, and the closing of more than 123,000 bank accounts, the majority of which belonged to Russians. He said his government fully implemented EU sanctions against Russia despite the financial and economic cost, and in return Russia suspended a tax treaty and imposed bans on currency export and payments to jurisdictions it considers “unfriendly,” including Cyprus. “I believe that the above-mentioned, he wrote, “refute the false claims that my administration strengthened economic ties with Russia or that | myself either served the economic interests of Russians or, the worst of all allegations, of friends of the Putin regime.”

He said the 2013 law establishing two executive central bank board members was, “in fact a parliamentary and not a governmental initiative and secured broad cross-party support.” He said the law was “an absolutely correct amendment” that more closely aligned bank governance to that of the other central banks and the ECB itself. The idea that law shifted powers from the governor to the executive directors or gave them “management control,” is “false,” he said, adding the law “continues to grant full competences to the Governor,” including the right to “assign responsibilities to the 2 Executive Board Members.” He also denied ignoring ECB demands. He said that as president he had no power over the composition of the Bank of Cyprus board, while the central bank governor did, and that Demetriades’ account of the dispute was “an attempt to justify his obvious time-consuming delays” in leading the bank out of resolution. Anastasiades added that the “real reasons” for Demetriades’ departure was the “A&M scandal.”

(In response, Demetriades said the A&M’s contract expired amid turmoil at the bank with the country in crisis. “We needed them,” he said “There was nothing wrong with the Alvarez contract; the only thing that was wrong was the way it was used, with the purpose of getting rid of me.”)

Russian influence over Cyprus banks, meanwhile, was reaching a high-water mark. The Bank of Cyprus’ new board now included the six Russians, including Vladimir Strzhalkovsky, Putin’s former KGB colleague. The single biggest shareholder was a company controlled by Viktor Vekselberg, a now-sanctioned Russian oligarch.

The Central Bank of Cyprus approved a Russian investor group to buy a controlling stake in the Cyprus Development Bank. That group included Alexey Kulikov, part owner of a bank that Russian authorities alleged helped orchestrate one of the largest money-laundering operations in history, moving $10 billion from Russia to Europe. In May 2014, the Central Bank of Russia revoked the license of a small Russian bank where Kulikov served as adviser to its chairman for money-laundering violations in a separate scandal. A month later, the Cypriot central bank agreed to the Kulikov group’s development bank acquisition. Kulikov was convicted of fraud and embezzlement related to the bank linked to the larger money laundering scandal and sentenced to a nine-year prison term.

Nicos Anastasiades meets with Vladimir Putin in Moscow on Oct. 24, 2017.

The next year Anastasiades traveled to Moscow to sign an economic cooperation “action” plan full of bilateral agreements and attend meetings with Putin. At a press conference, Putin noted that Russia accounted for 80 percent of Cyprus’ foreign investment, $33 billion, and that Cyprus was the second-leading investor in Russia at $65 billion. The two would eventually sign another “action” plan with seven more economic and trade agreements, among which was a deal to ease rules for financial transactions involving Russian state-owned banks.

“It is good when our money comes back to work in our economy,” Putin said.

The politics of money laundering

The European Central Bank finally took control of the eurozone’s banking system in November 2014 — partly in response to the reckless banking that helped to cause the euro crisis. With the introduction of the so-called Single Supervisory Mechanism, the ECB was now the direct regulator of the Bank of Cyprus, RCB and other big Cyprus banks; that meant the ECB had the power to conduct on-site inspections and grant — or withdraw — banking licenses. Among its new responsibilities, the ECB would make sure bank managers and board members were “at all times of sufficiently good repute,” one of five criteria for deciding if they were “fit and proper” to run their financial institution.

The ECB’s new powers were sweeping, with one notable exception: money laundering. The financial crime that most requires centralized oversight — that by definition involves multiple jurisdictions — was carefully carved out of the SSM.

No one wanted the concentration of powers in one agency that would make the prosecution of bad practices actually enforceable.

— Alexander Apostolides, an economist and banking historian at European University Cyprus

EU member-state regulators argued that money-laundering enforcement was an intrusion on national sovereignty (even though the SSM itself amounted to one of the most significant transfers of sovereignty since the EU was created); negotiators also did not see money laundering as the immediate systemic threat that bank-lending practices were. But in the anti-money-laundering field, technical and legal arguments are often used to disguise political and financial interests. The status quo largely insulates banks from liability while allowing international payments to flow, even as more than 99 percent of laundered money goes undetected, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

“The fragmentation over the fraud, money-laundering corruption and sanctions may be intentional,” Alexander Apostolides, an economist and banking historian at European University Cyprus, told ICIJ partner Paper Trail Media. “No one wanted the concentration of powers in one agency that would make the prosecution of bad practices actually enforceable.”

In the end, the job of battling Russian money laundering was left to the likes of the Central Bank of Cyprus, widely understood to be in the sway of a political class itself awash in Russian money. With the EU essentially tying its own hands in policing money laundering, the exposés started to roll in. In the spring of 2016, ICIJ, McClatchy, the Miami Herald, German daily Süddeutsche Zeitung and more than 100 other media partners published the landmark Panama Papers project, one of the most explosive exposés of the decade. Those stories sparked global protests and pushed the offshore financial system to the top of the global political agenda.

Revealed as a central player in these stories: RCB Bank. The series showed the Cyprus bank had funneled more than $800 million in lines of credit — unsecured — to a Caribbean shell company that moved money to other shell companies that traced directly to intimates of Putin himself. For just $1, the RCB-financed shell company gave the rights to $8 million in interest payments to Putin’s boyhood friend, Sergei Roldugin, who introduced Putin to his first wife, Lyudmila, and is godfather to Putin’s daughter Maria. A concert cellist turned billionaire, Roldugin is commonly referred to as “Putin’s wallet.” (At the time, RCB denied wrongdoing and said that any loans were secured.)

The so-called Mueller investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election discovered that the Bank of Cyprus had helped funnel money from Ukrainian kleptocrat Viktor Yanukovych to the future chairman of Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, Paul Manafort. (In press reports, the Bank of Cyprus said it cooperated in the U.S. probe.) In 2017, OCCRP found that Hellenic Bank, Cyprus’ second-largest bank, received over $500 million in proceeds from another notorious scheme known as the Russian Laundromat, which allegedly moved more than $20 billion out of Russia between 2011 and 2014. Hellenic didn’t reply to ICIJ’s request for comment.

Like RCB, Bank of Cyprus and Hellenic Bank were directly supervised by the European Central Bank. In 2020, ICIJ and its media partners published the FinCEN Files, which revealed that, in 2017, JPMorgan Chase reported suspicious wire transfers totaling more than $322 million involving shell companies in Cyprus and other secrecy jurisdictions that had done business with Manafort. At least $40.2 million involved the political consultant himself. One of the banks used in the transactions was Cyprus Popular Bank.

Through it all, U.S. and European politicians railed against Cyprus as a hub of laundered Russian money. The country’s reputation as a broken pipe in Europe’s financial infrastructure was now indisputable.

“Dear President Anastasiades,” wrote a group of 17 members of the European Parliament in October 2017. “We write to you with grave concern about the role that corrupt Russian government officials are playing in Cyprus in relation to the laundering of massive criminal schemes coming from Russia.”

Yet European financial institutions only pulled closer to RCB, bolstered by its status as an ECB-regulated bank.

‘This is over, it’s finished.’

The year 2018 marked Europe’s money-laundering meltdown. In February, the U.S. Treasury Department blacklisted ABLV Bank, Latvia’s third largest, as a “primary money laundering concern” related to the financing of a North Korean weapons program — spiraling the bank into liquidation. That year another roiling scandal blew open when a whistleblower revealed that an office of fewer than a dozen people at Danske Bank’s branch in Tallinn, Estonia, had laundered as much as $230 billion — nearly eight times Estonia’s gross domestic product — for a clientele largely from Russia and former Soviet republics and satellites. The scandals rocked the financial world, including the European Central Bank, which was now scrambling to explain itself.

“The ECB and anti-money laundering: What we can and cannot do,” declared the headline of an ECB press release that same year. The central bank explained that it didn’t have the power to investigate money laundering, which had been excluded from the SSM, and had to rely on local authorities; it could act only if money laundering posed a “prudential risk.” It acknowledged, however, that it could ask authorities for help for “fact-finding purposes” about money laundering if it felt it had “insufficient information” to properly supervise a bank. Critics further contended that a bank’s reliance on massive inflows from foreigners posed an obvious “prudential risk.”

“Everybody understands if you do supervise the business models, you can’t distance yourself from the risks that apply to the servicing of the nonresidents,” Dana Reizniece-Ozola, then Latvia’s finance minister, told the Financial Times. The ECB would later admit that money laundering indeed poses risks to banks’ viability; the EU is still working to establish a new centralized authority.

In a statement, the ECB said that under prevailing regulations, “it is not allowed to disclose any confidential supervisory information on specific credit institutions. Therefore, the ECB is restricted from disclosing any adopted supervisory measures addressed to Cypriot significant institutions.” It also said that under its guidelines, it “cannot discriminate qualifying shareholders depending on their nationality or country of origin – there is no legal basis for that.” The ECB added that in assessing existing or potential shareholders, it looks at “all information either provided as part of the file or publicly available – e.g. sanctions list, etc),” as well as a person’s connections to others, according to European guidelines. The ECB’s full responses to ICIJ’s questions are here.

Cyprus’ rise as a Russian money hub within Europe’s banking system raises questions over how the European Union should wield its influence.

Cyprus’ rise as a Russian money hub within Europe’s banking system raises questions over how the European Union should wield its influence.

Finger-pointing turned to Cyprus. In a scathing report to Congress in August 2018, the U.S. Treasury Department charged that the country “continues to host a large volume of suspicious Russian funds and investments,” slamming its “permissive” citizenship program, “weak” supervision of service providers and “lax” corporate rules that allowed “illicit actors” anonymous access to the international financial system.

As part of Cyprus Confidential, ICIJ combed the records of six Cypriot corporate services firms and a Latvian company that sells Cypriot corporate registry documents through a website called i-Cyprus. ICIJ found that Cyprus firms in the leaked data provided services to companies owned or controlled by 96 sanctioned Russians, 25 of whom had already been sanctioned before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 — including Viktor Vekselberg.

In May that year, Marshall Billingslea, then assistant Treasury secretary for terrorist financing, met with the island’s top regulators, according to the Wall Street Journal. He waved a list of Russian oligarchs likely to face penalties and mentioned the blacklisting of ABLV.

“You saw what happened in Latvia?” Billingslea said. “You don’t want anything like that happening here?”

“Bring it on,” a Cypriot regulator snapped back, the newspaper reported.

But the “Cyprus model” was already under siege. In June, after years of promises, the Central Bank of Cyprus finally ordered banks to close accounts for shell companies not engaged in legitimate business. The Cyprus Mail reported that banks closed well over 50,000 accounts and refused to onboard thousands of other customers. The Bank of Cyprus froze Vekselberg’s accounts, though he remained the largest shareholder. In 2019, Marshall Billingslea himself would hail Cyprus’ “enormous progress and improvements.” The amount of non-EU resident deposits began to tick down, from more than $10 billion in 2014 to about $7 billion five years later.

In November 2018, Cyprus Finance Minister Harris Georgiades candidly acknowledged the model’s problems in a forum on Cyprus’ economic future.

“Let’s be honest: We had billions and billions of deposits along with a company that was nothing but a shell with no employees and no physical presence,” he said. “This is over, it’s finished. Even if we wanted to continue with such a model we can’t, and there is no desire for such a model anymore.”

Still, more than a year later, Cyprus received a mixed report from Europe’s main anti-money-laundering advisory panel, which praised “increasingly sound supervisory practices of the Central Bank of Cyprus” but noted “major shortcomings.” Among them: “The competent authorities were not yet sufficiently pursuing money laundering from criminal proceeds generated outside of Cyprus, which pose the highest threat to the Cypriot financial system.”

The Russian invasion of February 2022 revealed the true price of Cyprus’ lucrative secrecy business. But the unbridled and audacious rise of a Russian money hub within Europe’s banking system only raises new questions about when — and under what circumstances — the EU will wield its considerable power when the next Cyprus emerges.