In the early hours of Monday, 10 October 2022, Russia pummelled Ukraine’s largest cities with missiles killing at least 20 people and wounding more than 100, according to Ukraine’s national emergency service. Russia has boasted about the surgical precision of its cruise missiles and claimed the attacks on 10 October targeted Ukraine’s military and security command centres and the national energy grid. However, open-source evidence shows that multiple missiles struck non-military targets, damaging residential buildings and hitting kindergartens and playgrounds.

The 10 October attacks marked Russia’s largest coordinated missile strikes since the beginning of the war. Yet the destruction didn’t end there. Missile strikes continued the next day with at least 28 launched on 11 October. The strikes left large numbers of civilians in Kyiv, Lviv, Vinnytsia, and Dnipro with no or sporadic access to electricity.

Cruise missile attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure continued into a second week on 17 October 2022, when Ukraine reported shooting down three cruise missiles flying towards Kyiv. On the morning of 18 October, new missile attacks were reported in at least three cities leaving some of them with no electricity. As of 18 October 2022, international prosecutors were investigating the targeting of civilian buildings and critical civilian infrastructure as potential war crimes.

Remnants of a Kalibr missile found near impact craters on 10 October in Konotop, Ukraine, (Source: Ukraine’s Defence Ministry). The fuselage wreckage shows the Kalibr’s tell-tale black broken stripes (top right image) and the bottom shows partly the 3M-14 inscription that adorns the weapon and can be seen in greater detail here).

Visual evidence and photographs of remains of the missiles show that many of that were launched on 10 and 11 October 2022 were winged cruise missiles, of the sea-launched Kalibr (3M-14), the land-launched R-500 (9M728) for the Iskander system, and air-launched Kh-101 types. These missiles are touted by Russia as high-precision weapons that only destroy relevant military targets. However, since the start of Russia’s invasion, long-range cruise missiles have repeatedly destroyed civilian infrastructure and caused hundreds of civilian deaths and injuries – for example when a cruise missile hit residential areas in Odesa and Mykolaiv earlier this summer.

In one single day in July, cruise missile attacks on the city of Vinnytsia are reported to have killed 27 civilians. These strikes, that hit non-military targets, suggest either that the missiles failed to follow their pre-programmed flight path, that targeting was based on defective intelligence information, or that civilian harm was intentional. In at least two cases in April and early June, Russian cruise missiles flew dangerously low above nuclear power stations, creating the risk of a nuclear accident in the event of a misfire or falling debris.

Russia’s Cruise Missiles

Despite hundreds of open-source images and videos showing the flight and deadly impact of cruise missiles, little is known about who exactly is responsible for setting their targets and for programming their flight paths. Attribution of the programming of the flight-path of these allegedly high-precision weapons is relevant as the deliberate or indiscriminate targeting of Ukrainian civilians and civilian infrastructure could constitute potential war crimes.

Following a six-month-long investigation, Bellingcat and its investigative partners The Insider and Der Spiegel were able to discover a hitherto secretive group of dozens of military engineers with an educational and professional background in missile programming. Phone metadata shows contacts between these individuals and their superiors spiked shortly before many of the high-precision Russian cruise missile strikes that have killed hundreds and deprived millions in Ukraine of access to electricity and heating. The group, which works from two locations – one at the Ministry of Defence headquarters in Moscow and another at the Admiralty headquarters in St. Petersburg – is buried deep within the Russian Armed Forces’ vast “Main Computation Centre of the General Staff”, often abbreviated as ГВЦ (GVC).

Most members identified by Bellingcat and partners are young men and women, including one husband-and-wife couple, many with IT and even computer-gaming backgrounds. Some also worked at Russia’s military command centre in Damascus in the period between 2016 and 2021, a timeframe during which Russia deployed cruise missiles in Syria. Others are recipients of various military awards, including from Russian President, Vladimir Putin.

Bellingcat approached each identified member of this clandestine GVC unit with an offer to confirm or deny our findings, and with a list of questions including who selects the targets and whether the civilian casualties are the result of computational error or intentional targeting of civilians. One senior officer, reached by phone by a reporter from our investigative partner The Insider, hung up as soon as he found out with whom he was speaking. All but two of the other military engineers either did not respond to calls and text messages or explicitly denied working for Russia’s armed forces or denied even knowing what GVC was, despite many being shown photographs in which they are seen posing in military uniform with GVC insignia. One of the engineers did not deny their affiliation to this unit but indicated they could not safely answer the questions we put to them, and thanked our team for alerting them to the upcoming publication. Another member shared with us, on condition of anonymity, certain contextual information about how the group was tasked with manually programming the sophisticated flight paths of Russia’s high-precision cruise missiles and several photographs of their commander Lt. Col. Igor Bagnyuk. This individual also provided group photos of the GVC computation group posing in front of a Ministry of Defence building in Moscow.

Method of Identification

The identification of this clandestine group within the Ministry of Defence was made by parsing through open-source data of thousands of graduates of Russia’s leading military institutes that focus on missile engineering and programming, in particular the Balashikha-based Military Academy of Strategic Missile Forces near Moscow, and the Military-Naval Engineering Institute based in the Pushkin suburb of St. Petersburg. A starting hypothesis was that these leading military institutes could be a training ground for at least some of the officers currently programming Russia’s most sophisticated long-range missiles.

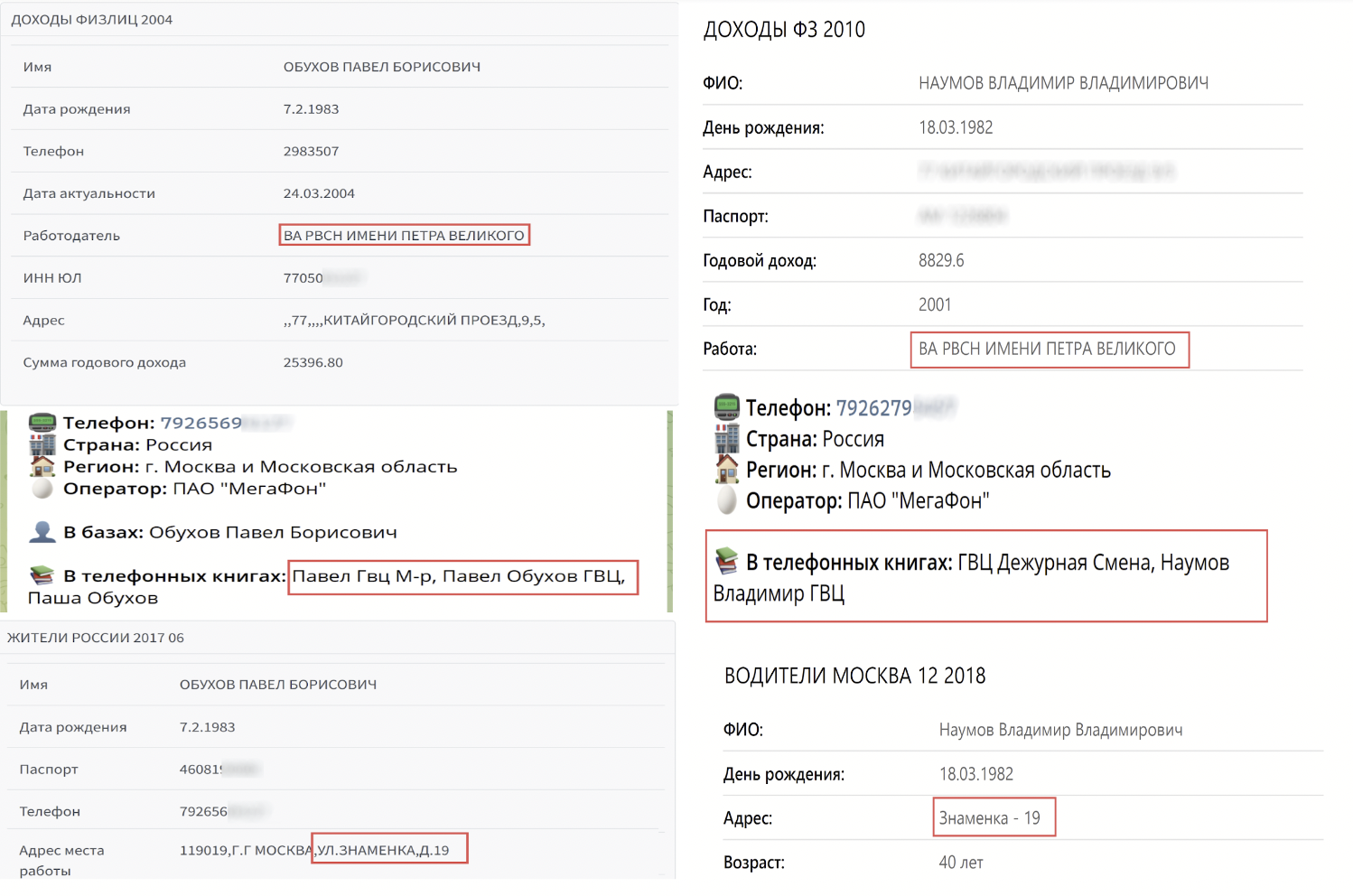

Bellingcat analysed leaked employment or telephone entry data on these graduates available via Russia’s underground data markets. This allowed us to discover that some of these people were referenced in phone contact lists, obtained from various data lookup Telegram bots such as Glaz Boga and HimeraSearch, as working at GVC (Главный Вычислительный Центр) or the Main Computation Centre of the Armed Forces of Russia. Notably, all of these military missile engineering graduates with a GVC reference linked to their phone numbers in these apps were registered as living and working at Znamenka Street 19 in Moscow — the official address of Russia’s Armed Forces General Staff.

Two graduates of Russia’s Academy of Strategic Missile Forces whose current work address is listed at Znamenka Street 19. Additional information from contact lists leaked online (see ‘в телефонных книгах’) shows that some have listed these individuals’ workplace as the GVC.

What is the GVC?

There is no public information linking the Main Computation Centre of the Armed Forces of Russia with the programming of cruise missiles. The function of the GVC has been opaquely described in military publications as “providing IT services” and “automation” to Russia’s armed forces. Despite its long history (according to Zvezda, a TV outlet affiliated with the Russian armed forces, it was established in 1963), sparse public mentions of this institute exist in present-day Russian media.

A rare example comes in the form of a 2018 award to a member of a military choir signed by Colonel Robert Baranov, named as the ‘director of the Main Computation Centre of the Armed Forces of Russia’. In 2021, a website focusing on Russia’s Volga Region reported that Baranov, who hails from the Republic of Chuvashia, had been promoted to Major General by presidential decree. The corresponding decree naming Baranov can be found on the Russian government’s website.

One of the engineers we identified as working for GVC received a “certificate of gratitude” from President Putin in 2020, according to his resume on a freelance job posting. However, Bellingcat was unable to find this man’s name in either of the publicly available listings of Russian recipients of the award from that year. In the same posting, he describes his education as “automated systems with a special application”.

An aggregated review of the educational and professional background of the people affiliated with GVC based on telephone contact lists shows that most of them graduated from either the Academy of Strategic Missile Forces (and in particular its Informatics Systems subsidiary in Serpukhov) or the Military Naval Engineering Institute. Some had prior military service as navy captains or ship engineers. Others had prior civilian work experience as corporate IT specialists or game designers.

How we Linked the GVC Team to Cruise Missile Strikes

Given these highly specialised technical skills, it seemed plausible that the GVC may be linked to programming the flight paths of Russia’s cruise missiles. Therefore Bellingcat obtained phone metadata records of the highest ranking individual publicly named as its director: Maj. Gen. Baranov. This method is similar to that employed by Bellingcat to track and trace the poisoners of Russian opposition politician Alexey Navalny, with data purchased from brokers who commonly offer such services. While this method would be impossible in most countries, Russia’s black market for data has helped journalists and activists piece together numerous significant investigations into the country’s military and secret services in recent years.

An analysis of 126 phone calls from 24 February to the end of April 2022 showed a correlation between significant Russian cruise missile attacks in Ukraine, and incoming calls prior to the missile strikes coming from one particular number that we identified as belonging to another senior officer working at the GVC. This officer is identified via phone contact listings and leaked residential databases as Lt. Col. Igor Bagnyuk, and was registered at the same address as the other known GVC officers at Znamenka 19.

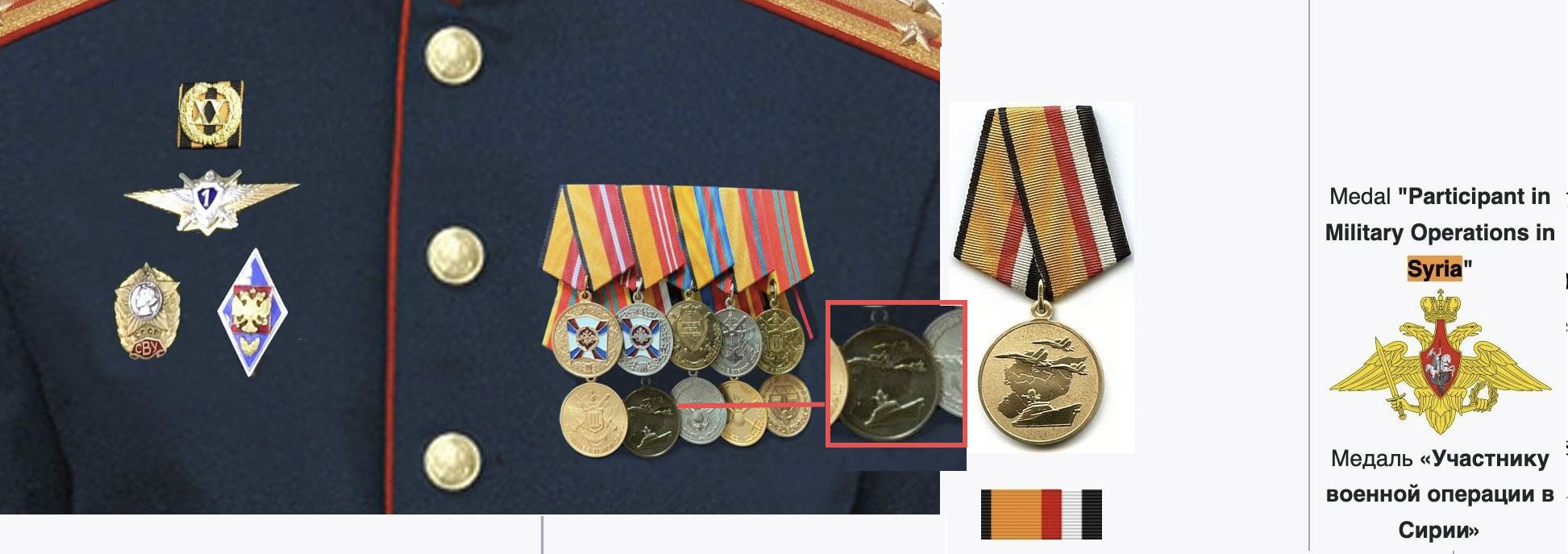

Records show the registered address of Lt. Col. Igor Bagnyuk.

On the assumption that Lt. Col. Bagnyuk was the senior-most officer potentially linked to the programming of long-range missiles, due to his direct communication with the commander of the group, we then obtained his phone metadata records for the period from the start of Russia’s invasion in Ukraine. Bagnyuk’s call records showed intensive communication with more than 20 military engineers and IT specialists associated with the GVC. Dipping back into the same Russian black market data sources, we then acquired several of the most frequently interacting phone numbers attributed to GVC officers. By analysing the cumulative body of phone records, we reconstructed a team of 33 military engineers who appeared to report or communicate frequently with Lt. Col. Bagnyuk.

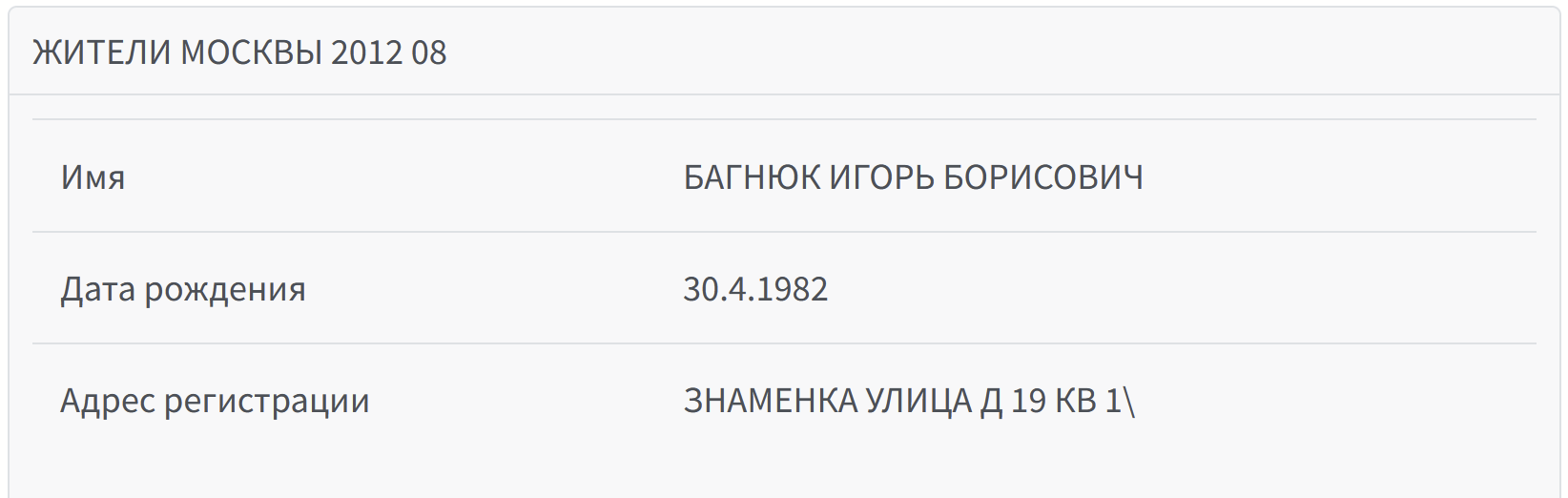

The clandestine group of engineers that we identified appears to consist of three teams of approximately 10 engineers each, with each team dedicated to one specific high-precision missile type.

Our initial hypothesis was based on “clustering” individual engineers based on their phone communication with one another. Three clusters were identified that talked primarily amongst the cluster and with their commanding officers. Then we compared peaks in the clusters’ communication with days and times when missile hits were publicly reported, and found a correlation to the three specific types of missiles. The specialisation of each engineer based on prior employment or education history matched the presumed focus, with officers coming from a military naval background being part of the sea-launched missile team etc).

The three missile types are: ЗМ-14 (Kalibr, sea-launched), R-500 (aka 9М728, for Iskander systems, (ground) launched), and Kh-101 (air-launched).

An organogram of the group within the GVC, reconstructed on the basis of call interactions between Lt. Col. Bagnyuk and members of the teams. Bellingcat and The Insider contacted each member with a right of reply. Most of the officers did not respond; the answers from the ones who replied are summarised further below.

One officer – named Anton Timoshinov, a lieutenant colonel like Bagnyuk – appeared to communicate with members of each of the three clusters, but did not communicate with anyone outranking Lt. Col. Bagnyuk, thus he appeared to be a subordinate of Bagnyuk but superior to the officers in the three sub-groups.

What are Russia’s high-precision missiles?

Russia’s army has been on a quest to develop long-range, high-precision cruise missiles since the middle of the 20th century. However, it has been capable of developing and perfecting conventional cruise missiles only in the last twenty years – long after their US counterparts were first deployed.

During the war in Ukraine, Russia has used three primary types of cruise missiles – all of which appear to have been first battle-tested in the war in Syria. These three types include sea-launched, airborne-launched and ground-launched cruise missiles.

Kalibr 3M-14 (Sea-launched)

A Kalibr cruise missile being launched from a Russian navy ship in the Caspian sea, photo: Russian Ministry of Defence.

Kalibr 3M-14, also known under the denomination 26 SS-N-30A, is the land-targets variation of the Kalibr family which also includes anti-ship and anti-submarine modifications. All three versions of the Kalibr share a vertical launch system that allow them to be launched with any number of Russian naval vessels including smaller corvettes and submarines. The missile was test-proven in Syria to be able to hit targets as distant as 1,800 km from the launch site.

While precise estimates are not available, Russia has launched hundreds of Kalibr missiles since the start of the invasion of Ukraine, with one media estimate of 225 missiles fired in just the first two months of the war. Each missile is estimated to cost approximately EUR 6.5 million (US $6.38 million).

Kh-101 (air-launched)

A Russian strategic bomber launches a Kh-101 in Syria in 2016. Screengrab from Russian Ministry of Defence video.

The Kh-101 is the conventional-warhead version of Russia’s air-launched cruise missiles. Like the Kalibr, it debuted in a real-war setting in Syria. Also like the Kalibr, the Kh-101 is designed to evade air defence systems by flying at low altitudes closely tracking the ground terrain; however its ability to defeat radar detection is reported to be more advanced, both due to lower flight altitudes and absorptive surface material. The Kh-101’s reported operating range is up to 2,800 km, and it can be launched from Tu-160, Tu-95MS, or Tu-22M3 strategic bombers. Each Kh-101 is reported to carry a 450 kg warhead that can include high-explosive, penetrative or or cluster munitions.

Launch of a R-500 cruise missile from an Iskander system during 2014 military exercises, photo: Russian Ministry of Defence.

The R-500 is the cruise version of the missiles launched from the vertical-launch Iskander-M missile complex, traditionally used to launch ballistic missiles, and was first deployed in 2013. Unlike the Kalibr and the Kh-101, it has a significantly shorter range of approximately 500 km, however can be made ready, targeted and launched with a very short lead time, with Russian weapons blogs claiming less than a minute is needed between launches aimed at different targets. It carries a conventional warhead of 500 kg but, like the Kh-101, can be modified to host a nuclear warhead. The conventional warheads may carry cluster, fuel-explosive and bunker-busting munition. Like the Kh-101, the R-500 also flies at a low altitude in order to avoid most standard radar discovery systems.

Flight-Path Planning and Precision

Russian authorities claim their cruise missiles are high-precision weapons and can hit targets with a deviation of not more than five to seven metres. However, Russian state-run media have reported that the precision may be in the range of 30 to 50 metres.

While the exact flight-path and target-seeking mechanism varies among the three types, various weapons and military publications describe how each generally follows route-adjusted initial flight path that depends both on astro-inertial navigation, which compares measurements from on-board gyroscopes and altimeters to a pre-programmed sequence and on satellite (Navistar) and GPS (GLONASS) route correction, as well as optical and correlation-extreme recognition of waypoints along the path and the final target.

Due to the complexity of interactions between the various inputs for the flight path and course adjustment, each missile’s flight path requires customised, individual planning. According to one of the members of the GVC team who agreed to answer questions on condition of anonymity, the pre-flight planning requires simulation of the complete flight path from launch site to target. The resulting flight path plan as well as the algorithm for course adjustments based on various inputs is loaded by the programmers onto a ruggedized memory stick, which is then passed on to the launch location and inserted into the missile.

Who are the Remote Control Killers?

A photo of the members of the GVC group from 2013, provided by one of the unit members anonymously. Right-most: Col. Igor Bagnyuk. Bellingcat geolocated this photo to the inner courtyard of the sprawling building of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces at Znamenka 19.

The background of the military engineers working for the GVC is diverse. It includes both people who spent all of their career in the army or navy, and subsequently received a military engineering specialisation, as well as young people who were recruited from civilian jobs usually linked to IT and computer science.

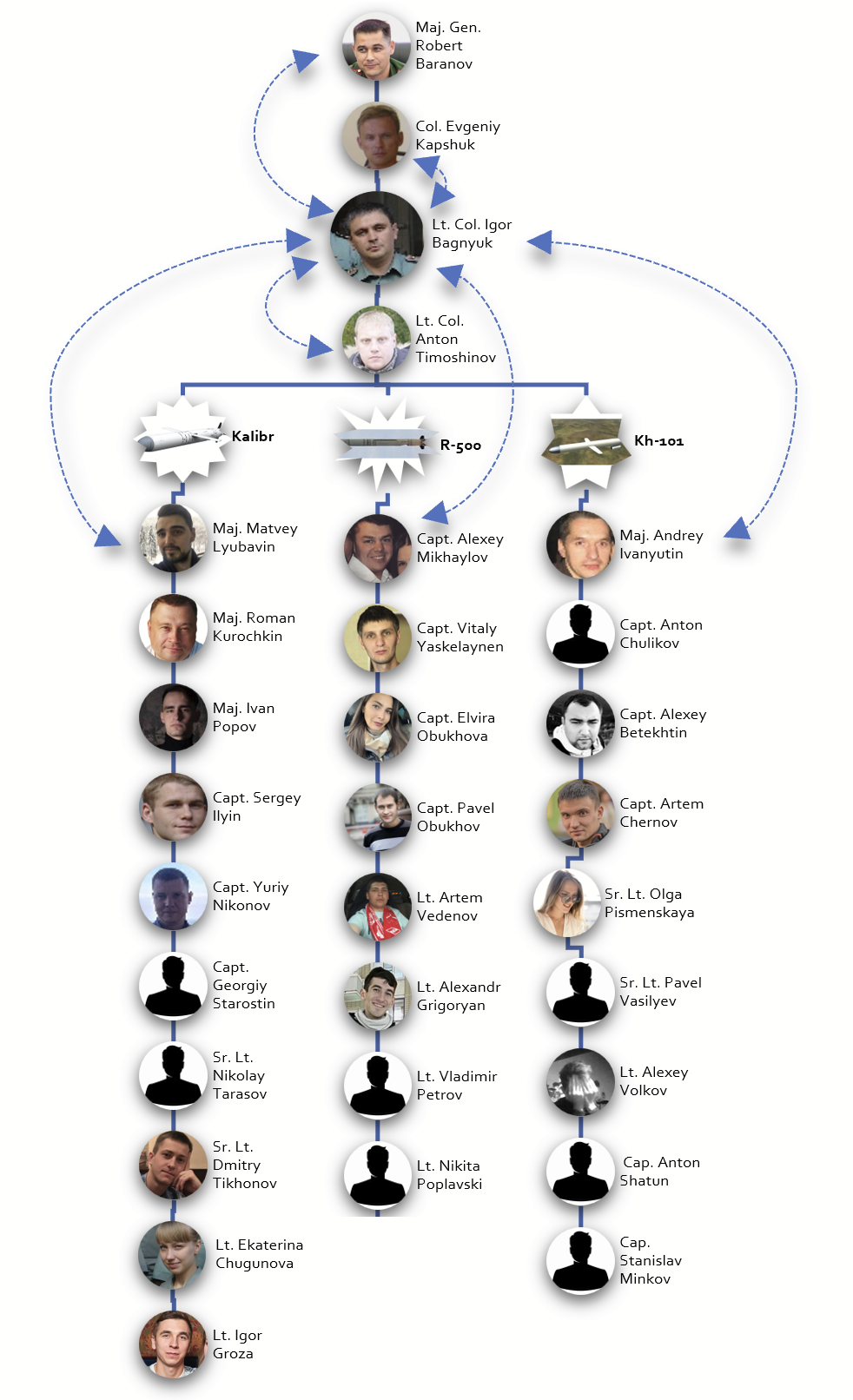

Igor Bagnyuk, photo provided by a member of the unit. He is a bearer of several military medals including the Military Valor 2nd Degree medal.

The direct commander of the missile pre-planners sub-unit at GVC appears to be Col. Igor Bagnyuk. This was established on the basis of the analysis of telephone data of eleven members of the group of engineers obtained from data sources on the Russian black market, including that of Bagnyuk himself, which showed a pattern of subordination in which each member communicated with him but he alone communicated with the superiors. Furthermore, he was identified – both by face recognition and by the military insignia – as the senior-most officer on the group photo with other GVC team members. Furthermore, the member of the team who engaged with reporters stated Bagnyuk was the direct commander.

Parts of Bagnyuk’s biography can be reconstructed from leaked data found in various aggregated databases, such as HimeraSearch and Glaz Boga. Born in Rīga in 1982, Lt. Col Bagnyuk in 2004 graduated from the Serpukhov subsidiary of the Academy of Strategic Missile Forces which specialises in IT systems for Russia’s missiles. He was deployed at military unit 29692 near the city of Vladimir until he was moved to Moscow to join GVC at some point before 2010.

The medals and orders of distinction on his photo, obtained from one of the GVC members who engaged with Bellingcat, shows that Bagnyuk was awarded a medal for “Participation in Military Operations in Syria”. This medal was awarded to Russian officers in the period between 2015 and 2020. Russian armed forces did fire both airplane-launched and sea-launched cruise missiles in the period between 2015 and 2017 in Syria, including reported 2016 strikes on Aleppo.

A medal worn by Lt Col. Igor Bagnyuk awarded for participation in the conflict in Syria.

The engagement in Syria of officers from the unit supervised by Bagnyuk can also be confirmed via open sources. In this photo, published on the Kremlin’s official website (archive), Russia’s President Putin is seen talking to Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad during a January 2021 visit to Damascus. The meeting is held inside Russia’s secure military command centre in Syria, as described in the accompanying Kremlin release. Sitting in a row behind the two leaders are several unnamed Russian officers. One of them appears to be Maj. Andrey Ivanyutin (archive), a member of the GVC unit with whom phone records show Bagnyuk has been communicating extensively during the current war. Facial comparison tools allowed Bellingcat to identify Ivanyutin’s VK page.

Reporting to Top Brass Before Attacks

Looking at Lt. Col. Bagnyuk’s phone metadata over a period of months, a pattern begins to emerge.

While Bagnyuk called his subordinates from the GVC team relatively often, he spoke with his commanders – Lt. Gen. Baranov and Col. Evgeniy Kapshuk – infrequently. A review of his calls to the top brass at the GVC show a correlation between these calls and impending large-scale missile attacks.

A month before the major October attacks, Bagnyuk spoke with Gen. Baranov on Saturday, 10 September, at 12:41pm. At the time of the call, Bagnyuk was at the office at Znamenka 19. The last call Bagnyuk made at 21:20 that evening was to Capt. Alexey Mikhaylov, an R-500 targeting specialist.

The next day, Sunday 11 September, the Russian Defence Ministry reported that “over the last 24 hours” Russia had launched an unknown number of R-500 missiles at Ukraine’s military deployment in Donbass. Later that same day, Russia launched 12 additional cruise missiles – six Kalibr and six air-launched Kh-101 – at Ukraine, in the first reported attempt to target Ukraine’s energy infrastructure.

On 12 September 2022, Bagnyuk flew to Rostov – near the border with Ukraine – his phone movements show. During the night of 12 to 13 September, his phone records detailed a flurry of calls. Between midnight and 02:00, he spoke four times with his superior Col. Kapshuk, and called his subordinates, Maj. Matvey Lyubavin (Kalibir specialist) and Capt. Alexey Mikhaylov (R-500 specialist), twice each.

The following day, 14 September, Russia’s Defence Ministry reported that it had conducted a “sudden night-time launch” of an Iskander cruise missile complex targeting a command centre of Ukraine’s armed forces. The launch was made from Ukrainian territory, according to Russia’s Ministry of Defence.

Screengrab from a video distributed by Russia’s Ministry of Defence showing the alleged night-time R-500 launch from an Iskander complex.

Later on the same day Russian planes launched eight Kh-101 cruise missiles at hydraulic infrastructure at Kryvyi Rih, leaving parts of the central Ukrainian city without water for days.

The earliest calls between Bagnyuk and Gen. Baranov identified by our team date back to 13 March 2022. On that morning the two spoke twice between 10:00 and 10:30. Earlier that morning, Russia had launched the deadliest salvo since the start of their invasion, firing 30 Kh-101 and Kalibr missiles. It left a reported toll of at least 35 killed and 134 wounded soldiers and officers. This included foreign military instructors at a military training camp in nearby Yavoriv.

An Hour to Kill

Bagnyuk’s phone records reveal an array of other information, including that he is an avid coin collector who spends a large portion of his time – including during working hours – on the phone with coin trading sites, such as eurocoin.ru. His obsession with numismatics appeared particularly striking on the morning of 10 October 2022, when, his phone records show, he communicated several times with the coin-trading website eurocoin.ru at 6:45 am, about an hour before a salvo of missiles hit Kyiv, killing dozens.

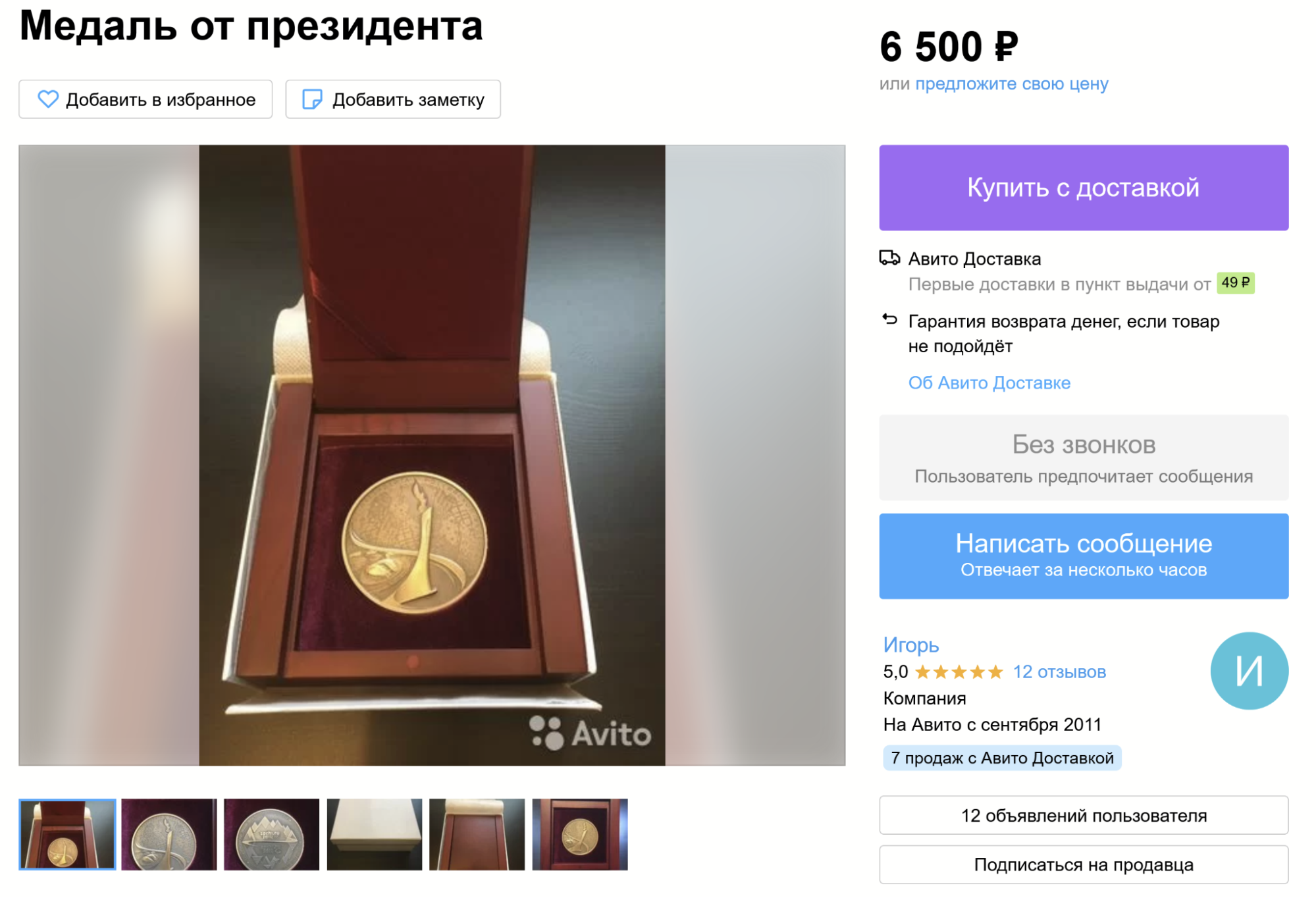

Lt. Col. Bagnyuk is also an active seller on Avito.ru, the Russian equivalent of Ebay. Amongst his recent sales of coins and consumer electronics, at the time of publication, he is currently offering for sale a medal awarded by President Putin in 2014. Based on descriptions of other offerings of the same type of medal, it was awarded “for contribution to the organisation of the Sochi Olympics”. It is not clear what role Bagnyuk may have played in relation to the Olympics. He is selling the medal from Putin for 6,500 rubles, or approximately $105.

A medal for sale on Lt Col. Bagnyuk’s Avito.ru site.

Phone records of Bagnyuk and his subordinates from the weeks prior to the 10 October attacks shows a surge of communication starting on 2 October and peaking on 9 October, with a total of 11 calls to engineers made on the last day before the strikes. Prior to 2 October there was a lull of communication for approximately two weeks, consistent also with the absence of reports of intensive cruise missile use. This suggests that the planning for the 10 October attack began approximately one week earlier, in line with intelligence information obtained by Ukrainian authorities. This timing also implies that the attack on the energy infrastructure may not have been a direct consequence of the partial destruction of the Kerch Bridge in Crimea on 8 October 2022.

The day before the missile attacks, beginning just after 15:00 on Sunday, 9 October, Bagnyuk called in a sequence three officers – engineers from the GVC team, each specialising in one of the three types of cruise missiles.

At 15:17 Bagnyuk telephoned Capt. Alexey Mikhaylov, a member of the sub-team specialising in the land-launched R-500 missiles. A few minutes later he made a call to Maj. Matvei Lyubavin, one of the senior engineers in the sea-launched Kalibr missiles sub-team. He called Lyubavin on his landline at the office, showing Lyubavin was at his desk on a Sunday afternoon.

After a pause of nearly two hours, at 17:10 Bagnyuk received a phone call from Col. Kapshuk, one of the deputy commanders of the GVC. After hanging up with his superior, Lt. Col. Bagnyuk immediately called Sr. Lt. Olga Chesnokova, a member of the sub-team specialising in the air-launched Kh-101 cruise missiles. Bagnyuk called Chesnokova twice in a row at 17:16 and 17:17, and then called back his superior Col. Kapshuk at 17:20. Thus, between 15:17 and 17:17, Lt. Col. Bagnyuk had called a member of each of the sub-units specialising in the three types of missiles that would be launched against Ukraine the following morning.

Lt. Col. Bagnyuk then made his way from his suburban home in the outskirts of Moscow to his office at Znamenka 19, the headquarters of the General Staff of Russia’s army. Cell tower metadata shows that he stayed at his office until late that evening. He made one last call to the chief of the GVC, Gen. Baranov, at 21:15, and then left for home.

Bagnyuk returned to the office just after 05:30 the next morning, 10 October 2022, his cell phone metadata shows. He arrived just in time for his online coin trade, an hour before the attacks on Ukraine began.

The Approach: Reaching out to the GVC Team

The military engineers from the missile flight-planning unit of GVC are young people mostly in their late twenties, with the four youngest members only 24 years old. While many of them had prior civilian mathematics or IT education, all of them underwent military engineering training at the Military Academy of Strategic Missile Forces or the Military-Naval Engineering Institute.

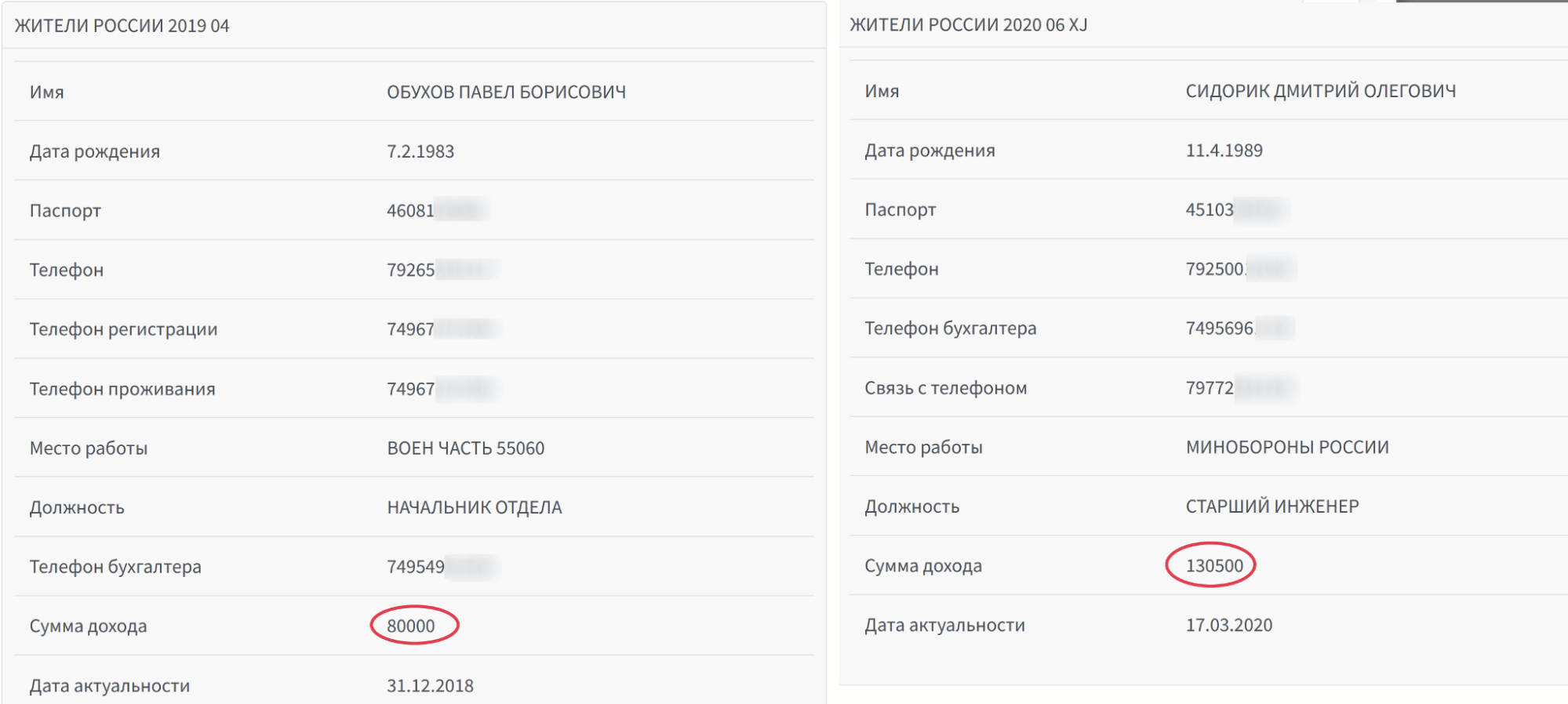

Unlike their military peers, most of whom are exposed to at least some personal risk near the front-line, these young people work from secure command centres in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and appear to go about their lives with little interference from a war in which they play a crucial role. While their current wartime pay levels are not known, leaked salary data for some of the members from 2018 to 2020, available in data aggregators such as Glaz Boga, suggests that the pay rates has been increasing, from a monthly average of Rub 80,000 (US$1,300) in 2018 to an average of Rub 130,000 ($2,100) in 2020.

Leaked salary data, source: HimeraSearch data aggregator.

Matvey Lyubavin appears to be one of Lt. Col. Bagnyuk’s senior-most subordinates based on their number of phone interactions. Lyubavin was born 1992 and finished the Nakhimov naval-military school in St. Petersburg in 2009. In 2014, he graduated from the Military-Naval Engineering Institute in St. Petersburg with a specialisation in “IT automation of special-purpose systems”.

After graduating he worked in civilian jobs, including in IT support for two banks and at a pharmaceutical R&D company. For several years he led a life of a regular Moscow urbanite, travelling abroad, organising fashion shows and tweeting detailed reviews on the latest movies. Lyubavin also took a stance on civic issues, retweeting support for messenger Telegram’s refusal to share data with Russian authorities and becoming a member of Active Citizen, an independent civic engagement programme. His phone number appears also in the leaked database of the Smart Voting participants – a strategic voting endeavour by Alexey Navlany’s anti-corruption foundation to steer votes away from the ruling United Russia party in favour of any other candidate.

Maj. Matvey Lybavin. Left: 2009 school graduation. Center: 2014, Naval Academy graduation. Right: 2022 resume photo.

Maj. Matvey Lybavin. Left: 2009 school graduation. Center: 2014, Naval Academy graduation. Right: 2022 resume photo.

By 2020, Lyubavin was already working for the secretive GVC flight pre-planning unit. According to his own resume, posted on a freelance job search website in March 2022, he received a certificate of gratitude from the Russian president. (Curiously, after the war had begun, Lyubavin appeared to believe that his day-job obligations at the GVC allowed him to generate supplementary income from copywriting and editing services, as well as from offering to “organise strategic research and training manuals for management” and “propose structuring and rhyming of the exposition”.)

Having observed the correlation of Lyubavin’s phone calls and the missile launches, in April 2022 Bellingcat approached him via a secure chat on Telegram, and asked him to comment on how he felt about the numerous civilian victims of the missile strikes. Lyubavin responded with the words: “Be professional; ask me concrete questions”.

We then reformulated the question to “Are the numerous civilian casualties during cruise missile strikes an intended outcome or the result of faulty targeting”. To this Lyubavin responded that he cannot answer this question. Following this response, the Telegram app notified the reporter that he made a screenshot of the chat. He refused to answer repeated further questions posed to him in the following months.

Yet, Maj. Matvey Lyubavin was one of the most candid members of the team when approached by Bellingcat for a right of reply. Another team member, whose identity is not known as they contacted reporters via a burner email account that was provided by Bellingcat and The Insider to all contacted members, shared two group photos of the GVC team and two photos of their commander, Lt. Col. Bagnyuk, wearing his many medals.

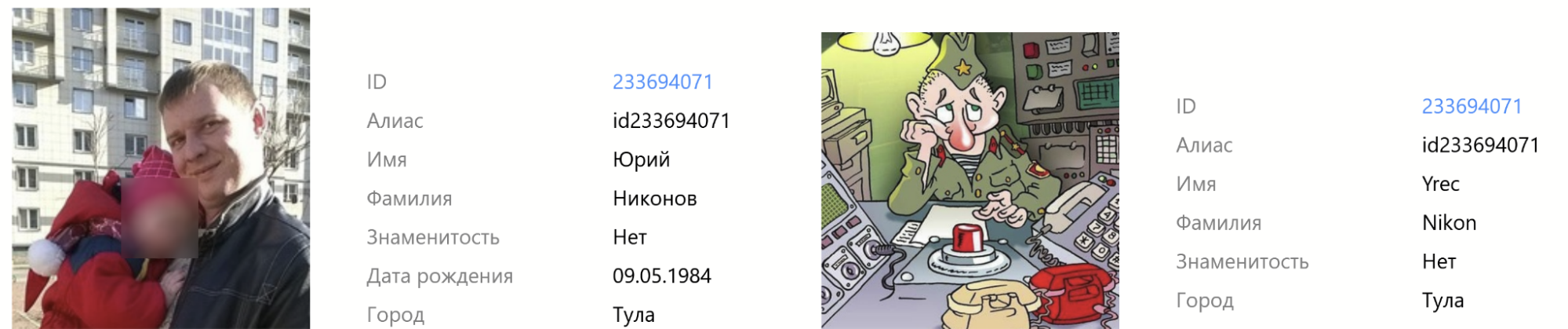

When a reporter from Bellingcat’s partner The Insider contacted Capt. Yuriy Nikonov, one of the engineers who most frequently interacted with Bagnyuk over the last six months, he denied knowing anything about the GVC or the ongoing war. He said he was a bus driver and that any claims of him being linked to the presumed targeting unit were “absolute nonsense”.

Following the approach by The Insider, Nikonov made his social media account on VK private. His new avatar became a photo of a cartoon character in Russian military uniform who is about to press a red button (the cartoon appears to have been used first as an illustration to a Russian soldier’s joke making fun of the notorious imprecision of Russian missile strikes). At press time, Capt. Yuriy Nikonov still had an active profile on a Russian dating website, where he described himself as an IT specialist, “looking perfect” and working for the state.

VK account of Capt. Yury Nikonov, from the Kalibr targeting unit, historical account data from 2019 and from July 2022 after he was contacted by Bellingcat. Source: vkfaces.com.

Other members of the GVC team reached by phone on the same numbers that were seen in Bagnyuk’s call records, also confirmed their identities but denied that they worked at the GVC or had anything to do with the Russian army.

For instance, Capt. Sergey Ilyin, who spoke with Bagnyuk by phone more than 30 times over the last four months, and whose own phone records show that he communicated with eight other members of the Kalibr sub-team, often at times correlated to missile attacks, told our partner The Insider that he is a “self-employed plumber”, and that his only brush with computations were just “such measurements that come in handy during plumbing work”. Yet, Ilyin appears in military uniform in a group photo with other military engineers bearing the insignia of the GVC.

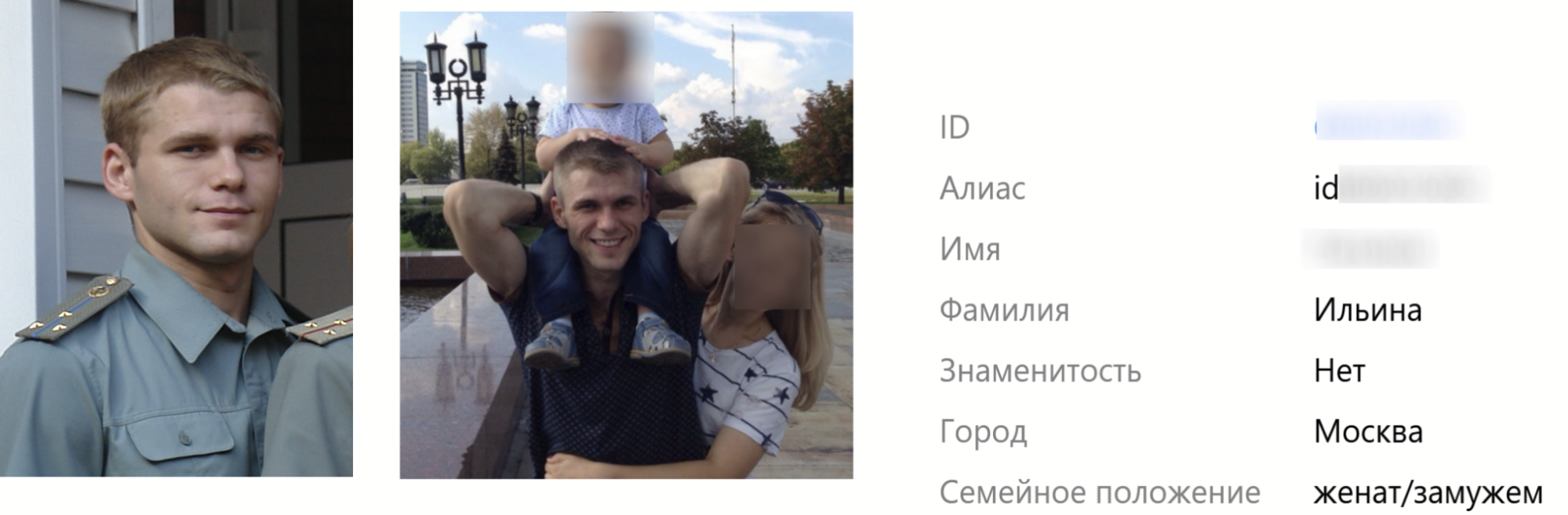

Left, Capt. Ilyin in the GVC group photo. Right, a family photo from his wife’s social media account that aided his eventual identification.

Another member of the team appearing in Bagnyuk’s phone calls around the time of missile attacks was Artem Vedenov. He took our call and confirmed his name, but said he works on a farm, and offered to the reporter to explain how to butcher a pig or pluck a chicken.

Maj. Ivan Popov, another Kalibr engineer with a degree from the St. Petersburg Military Naval Engineering Academy, said he was a self-learner in Python but had never heard about the GVC or about programming missile paths. Lt. Ekaterina Chugunova, also from the Kalibr subunit, said she was a florist, and insisted the call was to a wrong number.

When another GVC engineer, Vladimir Vorobyev, who denied having anything to do with the Ministry of Defence and with the GVC, was shown a photograph of himself in military uniform bearing the GVC insignia, he said this was the first time in his life he saw this photo, and expressed shock that he was in a military uniform.

Source: Bellingcat