Boris and Arkady Rotenberg were two of the most prominent Russian oligarchs to be sanctioned after the Kremlin’s 2014 annexation of Crimea. Never-before-seen insider documents now offer unprecedented insight into how they shielded their fortune — and who helped them do it.

Key Findings

- After the Rotenberg brothers were sanctioned in 2014, a flurry of corporate restructurings, asset transfers, and other schemes helped protect their worldwide assets.

- For years, they managed to keep hold of properties including a villa on the Spanish coast and luxury yachts, as well as companies in offshore tax havens.

- The efforts to preserve their empire were coordinated by a Russian businessman, his employees, and hired specialists — from lawyers to bankers to asset managers — from multiple Western countries.

- In Russia, they moved assets into special investment vehicles that obscured their ownership. These “closed mutual funds” are obliged to reveal nothing about whose wealth they’re storing.

- They also used proxies to store their wealth, including a bodyguard, trusted employees — and a woman who appears to be Arkady Rotenberg’s never-before-reported romantic partner.

Growing up in Leningrad, two brothers named Arkady and Boris Rotenberg took martial arts classes alongside Russia’s future president, Vladimir Putin.

The relationship endured, and as Putin’s political clout grew, so did the Rotenbergs’ wealth. Thanks in part to lucrative state contracts, their riches grew into the billions during their childhood friend’s rule.

But when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014, the Rotenbergs’ close ties to their old sparring partner drew unwelcome attention. Hit with sanctions, their vast foreign assets at risk, the brothers scrambled to shift them out of reach of Western regulators.

They had a lot to protect and, almost a decade later, they remain incredibly wealthy: Forbes magazine estimated their combined wealth at $4.9 billion this year.

As Putin’s renewed invasion of Ukraine racks up ever more murdered civilians and ruined cities, and the world’s most powerful countries continue to target the interests of those that are helping the Russian president, the question of how two members of Putin’s inner circle managed to escape serious consequences becomes more pressing than ever.

Credit: Sipa US/Alamy Stock PhotoVladimir Putin and Arkady Rotenberg at the presentation of state awards to outstanding citizens of Russia in 2013.

Now, a new email leak offers unprecedented insight into just that — highlighting, above all, the essential role that Western lawyers, bankers, and corporate service providers have played in helping the Rotenbergs safeguard their vast collection of assets.

The leaked archive, which consists of over 50,000 documents and emails sent between 2013 and 2020, was obtained by IStories and OCCRP and shared with 15 other media outlets.

The resulting investigative series, dubbed the Rotenberg Files, reveals how these enablers made it all possible. A central figure was Maxim Viktorov, a 50-year-old Moscow-born businessman, whose Russian management company and law firm played a crucial role in coordinating the Rotenbergs’ worldwide affairs after they were sanctioned.

Viktorov does not exude the aura of a powerful operator: When he appears in the media, it’s usually in association with his passion for rare Italian violins. In 2009, he paid a reported $3.9 million — “well in excess” of any previous record, according to auction house Sotheby’s — for an 18th-century instrument.

But while this exorbitant purchase made headlines, the scope of Viktorov’s work for the Rotenbergs was unreported until now.

For example, a few months after the brothers were sanctioned in 2014, Viktorov received a direct instruction from Boris’s son Roman: “We need to discuss and prepare documents,” he wrote.

It went on to describe a convoluted corporate restructuring plan intended to preserve the Rotenberg brothers’ share in Helsinki Halli, a major Finnish arena that hosted concerts, ice hockey, and other sporting events.

The plan was to be conducted in absolute secrecy: “These documents should be prepared inside the family by a trusted lawyer and nobody else should know about the existence of these documents,” the memo read.

The scheme appeared to be a success: The Rotenberg family managed, for years, to hold onto their share in the arena through Roman. (It was finally frozen after Roman, too, was sanctioned in 2022.)

This early example typified the subsequent years, in which — aided by Viktorov, his colleagues, and a host of hired specialists — the Rotenberg family used a range of manipulative techniques to shift around their assets, protecting them from Western sanctions.

The archive shows companies moving around the world like chess pieces, new bank accounts opening just as others were closed, and ownership structures morphing in response to new sanctions or questions from regulators.

When regulators asked tough questions about company owners, Viktorov and his team worked with trusted corporate service providers to move Rotenberg companies to less demanding jurisdictions. In Russia, his Evocorp Management Company LLC managed some of the brothers’ valuable assets after they were put under the control of ultra-secretive investment funds, which he portrayed as his own.

Finally, the archive reveals how various third parties — including a man reported to be Boris Rotenberg’s onetime bodyguard and a 36-year-old Latvian cosmetologist who appears to be Arkady Rotenberg’s secret romantic partner — took on the ownership of some of the brothers’ valuable assets.

Viktorov said neither he nor any of his companies had ever violated any laws, “in particular, the U.S. and EU sanctions legislation.” He described reporters’ findings as “erroneous” and said the shareholders of funds managed by his company are not sanctioned individuals.

Boris and Arkady Rotenberg, and members of their family, did not respond to emailed questions.

Tom Keatinge, director of the Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies at the U.K.-based Royal United Services Institute, said that historically weak enforcement by sanctions authorities meant that managing assets for wealthy sanctioned individuals did not carry much risk and was highly profitable.

“The paycheck is often worth it. You see very few cases of individuals being added to sanctions lists — let alone prosecuted — for facilitating sanctions evasion,” Keatinge told OCCRP. “To change people’s attitudes, we need some heads on spikes.”

Nosy Regulators

Among the situations that called for Viktorov and his colleagues’ attention was when regulators in offshore jurisdictions raised questions about Rotenberg assets. This included the British Virgin Islands (BVI), a jurisdiction not known for aggressively policing companies.

In 2016, a large section of the Rotenbergs’ financial empire was put at risk when BVI regulators started demanding that corporate service providers stop working with any companies owned by people sanctioned by the United States.

ILS Legal Services S.A., a company registered in Panama that was working with Viktorov on the Rotenbergs’ affairs, sounded the alarm.

“We have a serious issue,” wrote ILS in an email to Elena Ruzyak, a Rotenberg employee and fixer who worked closely with Viktorov.

ILS was notifying Ruzyak that BVI authorities were asking for the identities of the beneficial owners of at least 18 companies that belonged to the Rotenbergs or their intermediaries.

“Apparently the BVI Financial Services Authority obliges the BVI agents to resign from companies whose [] is listed in the…(US sanctions),” ILS wrote.

Referring to the brothers by their initials, the ILS email listed a series of “BR Companies” that were at issue and explained that, for “the Companies owned by AR,” there was “the additional complication of the EU sanctions.” (While both brothers were under U.S. sanctions in 2016, only Arkady had been blacklisted by the EU at that time.)

But the mention of Arkady appeared to trigger a strong response.

Seemingly alarmed, Ruzyak quickly replied: “It’s all BR!!!!!!!!!!!!”

It’s not clear whether this meant all the companies really belonged to Boris, or whether she was seeking to cover up a paper trail. In any event, the ILS response was swift and contrite: “Sorry, yes BR. It’s all about BR. We are already spinning like a snake on a pitchfork.”

Boris also would have had reason to be alarmed: Leaked documents and company records obtained by reporters show these companies held some of his most prized assets, including the Rahil, a luxury yacht with five guest suites and a nine-person crew, plus interests in at least six properties in southeast France.

“We have been dealing with the matter for the past 10 days trying to find a solution,” ILS wrote to Ruzyak.

To deal with the new regulations, ILS suggested a familiar solution: Replace the Rotenbergs with proxies who would sign deeds of trust, allowing them to appear as the companies’ ultimate owners, and then give authorities those names.

“We can name some trusted person as a nominal [beneficial owner] and issue a trust declaration in favor of Rotenberg,” ILS wrote.

After Ruzyak forwarded the exchange to Viktorov, he signed off on the idea: “I agree,” he wrote. “Let them prepare it.”

The scramble to find proxies began.

In an email to Viktorov, Ruzyak suggested a man named Aleksandr Kozlov, who has worked as Rotenberg’s bodyguard, as one possibility, but noted that his ties to the oligarch’s other companies — including, her email implies, a company called Frasgo Holding Corp. — would make him a less-than-ideal candidate.

“I am racking my brains, I thought of Sashka [Aleksandr] Kozlov but all those frasgos make it awkward (((((((((((((,” Ruzyak wrote, punctuating her email with 13 sad faces.

Nevertheless, registry data indicate Kozlov was indeed made the beneficial owner of at least one of the BVI firms: Medexlite Limited, which owned another luxury yacht also called the Rahil.

Two other assets — apartments in the heart of Riga, Latvia — were transferred away from one of the Rotenbergs’ BVI firm Narcius Investments Limited and registered in Ruzyak’s name, according to Latvian property records.

Eight of the 18 BVI companies mentioned in the ILS email were ultimately dissolved, and two relocated to Cyprus.

ILS, Ruzyak, and Kozlov all failed to respond to emailed questions.

Irene Kenyon, a former U.S. Treasury officer, describes Cyprus as “another BVI” for the Russians. It was “their little black box,” she said, “where they can register stuff and hide assets. … It was considered a secrecy jurisdiction.”

The leaked records don’t show what was done with the remaining problematic BVI companies.

But they do reveal another issue raised by U.S. sanctions against Boris Rotenberg: His ability to conduct banking transactions with his own wife.

Placating Bankers

In 1997, the French bank Société Générale set up a branch in the super-wealthy principality of Monaco. This office is not shy about its customer base, dedicating itself to “High Net Worth” clients and offering a range of services from Monaco legal experts, “wealth engineers,” and other specialists.

Such a bank would seem like the perfect place for a Rotenberg to hold assets. And indeed, leaked emails show Boris Rotenberg, his wife Karina, and ten of his companies held accounts with Société Générale in Monaco.

But in October 2015 — over a year after Rotenberg was sanctioned by the U.S. — the head of the Russia desk at the bank’s Monaco unit noted in an email to Viktorov that Rotenberg’s wife Karina was a U.S. citizen — and that it was “forbidden” for “U.S. persons [to engage] in transactions that involve a person subject to sanctions measures.”

In effect, the bank officer was asking whether the sanctions against Boris Rotenberg forbid him from sending money to his own wife.

“What is your interpretation of OFAC rules with regard to the US citizenship of Mrs K. ROT?” she asked Viktorov, referring to the U.S. Treasury office responsible for sanctions implementation. “Have you taken steps towards OFAC? What is the intended purpose of this approach?”

“We would appreciate that you answer us with detailed responses, argued and documented,” she wrote.

In fact, the bank had already frozen Rotenberg’s accounts. “We are waiting for your reply,” the bank officer wrote a couple of days later. “Your response will allow us to consider a position concerning the accounts bloqued [sic] by the bank.”

By the first few days of the following month, Viktorov and Sergey Markov, a former Soviet diplomat-turned-businessman who was also helping the Rotenbergs, were already corresponding with a wealth management company willing to help “the client” find alternative banking services.

This firm, LJ Partnership, based in London at the time, advertised itself as a “leading international, privately-held family office” that is “responsible for discreetly serving the needs of a select group of families.”

In addition to offering tailored investment advice and help building “onshore and offshore” corporate structures, it offers services including “yacht and aviation charter,” “close protection services,” and “lifestyle and travel administration.”

What Viktorov and Markov really needed, however, was help getting Rotenberg’s money out of the frozen Société Générale accounts as soon as possible. “The client is keen that work should begin soonest,” Markov wrote to an LJ Partnership executive.

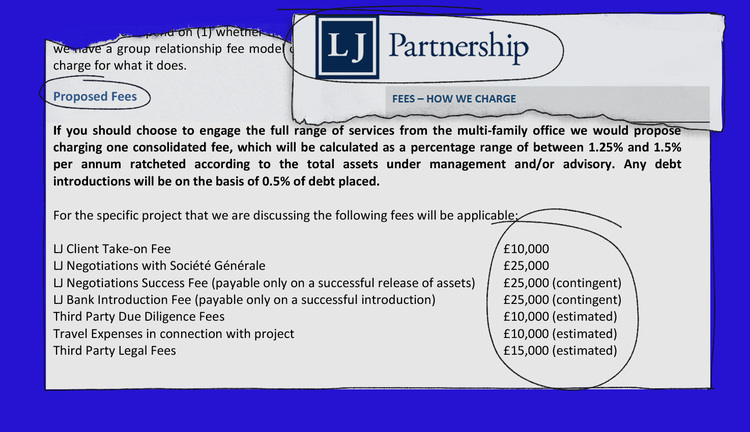

Credit: James O’Brien (OCCRP) / The Rotenberg FilesA list of fees provided by LJ Partnership to Viktorov and Markov, including £25,000 ($35,000) for “successful release of assets” frozen due to sanctions.

LJ Partnership then sent Markov a plan proposal. For 70,000 British pounds ($100,000) in fees and expenses — plus an additional 50,000-pound ($70,000) bonus if everything went well — the company offered representation in “discussions with Société Générale Monaco to achieve a release of certain assets” and introductions “to a new banking relationship … to achieve the transferral of assets from Société Générale.”

As its “client” for this project, LJ Partnership took on Viktorov’s U.K. company, Legal Intelligence Group Ltd, rather than Rotenberg himself, creating a buffer between the wealth management firm and the sanctioned Russian billionaire.

The operation, later dubbed “Project Sun,” soon got underway.

To lead the charge against Société Générale, LJ Partnership recommended an international law firm, Charles Russell Speechlys LLP. In an initial memo, the firm’s legal team offered a possible argument: “It would appear likely that SOCGEN’s actions in freezing accounts without the knowledge or consent of your client may amount to a breach of [its] contracts [with him].”

Soon, a from one of the firm’s lawyers in its Paris office were forwarded to Société Générale. The letters set out “our understanding of the legal position,” the LJ Partnership executive said. “I am sending these to you in draft so that we have the chance to discuss the matter again informally to attempt to find a solution,” he added.

The letters acknowledged that “in October 2015, my clients learned that their assets had been frozen by the bank … [as a] consequence of an individual measure taken against Mr Boris ROTENBERG by the American administration.”

However, they continued, “the bank’s decision [to freeze the accounts] … violates the binding conventions signed between the bank and my clients.”

Furthermore, they pointed out, no action had been taken against his clients — Boris and Karina Rotenberg and five of their companies — by France, Monaco, or any . According to the laws of both France and Monaco, the lawyer argued, “assets’ freezing measures can be undertaken only pursuant to a ministerial decision. There is none in the present case.”

Meanwhile, LJ Partnership continued to hunt for a new bank for Rotenberg. They suggested a range of options, including lenders in Singapore, the Bahamas, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein.

A deal was eventually struck with the Luxembourg-headquartered Banque Havilland S.A., a controversial elite lender owned by the well-connected Rowland family.

The leaked emails detail how LJ Partnership helped set up a meeting between Rotenberg and the Rowlands in Geneva. The meeting was scrapped, however, after the Russian oligarch — referred to by Markov as “the client” — had to cancel, leaving Markov apologizing for the “very embarrassing” situation.

A new meeting was then proposed in Monaco in April 2016. LJ Partnership relayed an invitation from the Rowland family to meet on their yacht in the city’s harbor.

“This is perfect,” Markov replied. “The client also has a yacht in Monaco Harbour, so small talk at the outset will be smooth.” Markov added that he and Maxim Viktorov would also arrive for the meeting “on Sunday evening.”

Markov told OCCRP he was not “an associate of Boris Rotenberg” and had “never received any money from him nor done any business with him.” He said he had long been “friends and business partners” with Viktorov and said their interactions and activities were lawful.

The meeting appears to have gone well. LJ Partnership soon confirmed that Banque Havilland was ready to take Rotenberg on: “The plan with the bank will be first to open the corporate account and then to open the personal accounts,” the company’s executive wrote. “It will be a two stage process.”

Leaked records indicate Banque Havilland accounts were opened for Rotenberg companies in the BVI and that Viktorov was appointed as a legal representative for them.

Payment instructions found in the email leak confirm that, in 2017, Karina Rotenberg sent 500,000 euros, in two payments, to her Banque Havilland Monaco account from an account in Moscow.

In a statement sent by a representative, Banque Havilland said it had had “always complied with all relevant sanctions in the countries we operate,” including in the U.S. and EU, and that it rejected “any suggestion of wrongdoing or suggestion that banking services have been provided to sanctioned individuals.”

Markov said any business between Boris Rotenberg and Banque Havilland “would have been up to them and perfectly legal subject to due diligence.”

The Rowlands could not be reached for comment and Banque Havilland said it could not comment on their behalf.

Matters do not appear to have gone so smoothly with the frozen accounts at Société Générale, however.

While emails suggest the French bank released some of Rotenberg’s funds early in 2016, negotiations over the frozen accounts appeared to hit some snags. The law firm LJ Partnership had engaged, Charles Russell Speechlys, ended up withdrawing from the project, though it is not clear exactly why. After they failed to find new representation, LJ Partnership said it would have to withdraw as well.

LJ Partnership, which was since rebranded Alvarium, did not respond to emailed questions or phone calls. Charles Russell Speechlys did not respond to a request for comment.

Eventually, the emails show Société Générale agreed to provide Boris Rotenberg with banking services under strict conditions, including not having any accounts connected to his wife, as the bank sought repayment of outstanding multimillion dollar loans to the Russian oligarch.

Société Générale said it could not comment on specifics due to banking secrecy rules, but added that it “strictly complies” with all laws and regulations and “diligently implements…international sanctions.”

Secret Funds

The sanctions against the Rotenberg brothers did not only have an impact abroad: They also prompted them to restructure at least some of their Russian holdings for greater secrecy.

Special investment vehicles called “closed mutual funds,” abbreviated in Russian as “ZPIFs,” were used to hold these assets. These structures, which are not considered legal entities under Russian law, are not obliged to reveal their shareholders, and cannot go bankrupt or have their assets confiscated, were managed by Viktorov and his team.

The secretive nature of ZPIFs and incomplete Russian corporate records means it’s often impossible to track who really owns them or what assets they hold.

But contained within the leaked emails is a rare find: Official minutes from a July 2017 meeting at the Central Bank of Russia. The document reveals that — at least as of that time — 13 ZPIFs managed by Viktorov’s company, Evocorp, were owned by or linked to the Rotenbergs.

These structures contained some high-profile assets, according to the Central Bank document, including the Moskvarium, a Moscow aquarium billed as Europe’s largest, and an imposing villa on Spain’s Mediterranean coast.

Credit: Dmitry Ivanov., CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsAn aquarium in Moscow, Moskvarium – one of the assets linked to the Rotenbergs in a Russian Central Bank document.

They also included shares in the Prosveshcheniye (“Enlightenment”) publishing house — a major player on the Russian market that regularly fulfilled government contracts for textbooks. (In 2017, a representative of Arkady Rotenberg told the Russian business paper Vedomosti that he had sold his share in the publisher.)

A leaked Evocorp report from 2018 shows that seven of these funds were still managed by the company a year later, while some had been transferred to a new fund manager, Severnaya Egida LLC (“Northern Aegis”).

The leaked emails show that, in their responses to queries about the shareholders of the ZPIFs or the companies they owned, Evocorp employees represented Viktorov as the ultimate owner.

“There is a practice where the General Director of the Management Company is recognized as the ultimate beneficiary,” wrote one Evocorp employee when asked how to respond to queries about the true owners of the Moskvarium.

The same response was given to two banks — SMP Bank and Sberbank — when they asked for more information about the beneficiaries of the ZPIFs or their companies. Evocorp responded with letters saying that Viktorov himself was the “ultimate beneficial owner” of the relevant company.

The leak does not show how SMP responded, but such explanations raised eyebrows at state-owned Sberbank.

“We need to understand who the fund’s shareholders are, not the managing company,” a Sberbank official wrote in 2017 to an employee of RG-Development, a major real estate firm held by one of the ZPIFs that, according to the email leak, Evocorp appeared to have managed for the Rotenbergs.

The RG-Development employee then wrote to their colleagues, telling them that the bank “strongly suggests that [RG-Development] close all settlement accounts with Sberbank, because we, in their opinion, are a company affiliated with persons from the ‘sanctions list.’ They sent us a notice to close.”

But the emails suggest the matter may have been resolved: A few days later, the RG-Development employee wrote to Evocorp to say that the Sberbank official would see if they could “get by’’ with a letter from RG-Development saying it did not have information on the ZPIF’s shareholders. If that didn’t work, Evocorp would send Sberbank another letter stating no sanctioned individuals were among the fund’s shareholders.

Sberbank did not respond to a request for comment.

Even with the built-in secrecy of the ZPIF structure, Evocorp took great pains to make sure information about the Rotenbergs remained secret.

In 2017, an employee of SDK Garant LLC, a Russian investment fund management company apparently hired by Evocorp to manage some of the ZPIFs, wrote to colleagues and Evocorp staff to say they were entrusting a new employee with the administration of one of Evocorp’s funds.

Evocorp’s CEO at the time quickly wrote back, chastising the decision.

“It is critically important for us that information about the fund’s shareholders should not be shared,” he wrote. “I think that transfering management of this fund to a new young manager is a violation of our agreement with SDK Garant.”

A Romantic Partner?

Among the ZPIFs that the leaked Central Bank document revealed were managed by Evocorp was one whose owner comes as somewhat of a surprise: A 36-year-old Latvian cosmetologist named Marija Borodunova.

The document shows that, as of mid-2017, Borodunova controlled 80 percent of RG-Development, the major real estate firm, through the ZPIF called Lontano.

Reporters found that she owned several other valuable assets: A luxury Monaco apartment in a landmark building which she rented to a Rotenberg company for 260,000 euros ($275,000) per month in 2017 and, with her two young daughters, a 4.25-million-euro ($4.5 million) villa on the French Riviera.

According to a leak of Russian tax records seen by reporters, Borodunova earned $25.5 million in 2020 alone.

Borodunova did not respond to emailed questions.

One clue to how she ended up with such wealth is provided by two sources who spoke to reporters on condition of anonymity due to fears over their security. Both described Borodunova as Arkady Rotenberg’s “unofficial wife.”

One of them, who is acquainted with members of Arkady’s entourage, said that Arkady’s relationship with Borodunova was not public, “but people close to them have known … for a long time.”

Reporters could not independently verify the sources’ claims. But Getcontact, an app that reveals the names under which a telephone number has been saved by its contacts, provides further corroboration: In at least a dozen cases, Borodunova’s number was saved in friends’ contact lists as some variation of “Maria Rotenberg.”