In six months, you’ll go home, having received a pardon. (…) Those who come with us and on the first day say, ‘I ended up somewhere I shouldn’t have’, we’ll mark a deserter and execute. (…) You have five minutes to decide.” Bellingcat published investigative journalism.

So said Yevgeny Prigozhin, self-confessed founder of the Russian private military company Wagner, to a group of inmates at Penal Colony 6 in Yoshkar Ola, capital of the region of Mari El, 645 kilometres east of Moscow. After the video from the prison surfaced in September 2022, the same pitch went out to convicts across Russia.

But on February 9, Prigozhin confirmed in a response published on social media to a Russian TV station that Wagner had ceased hiring convicts. “We are fulfilling all obligations towards those currently working for us”, he wrote.

As Bellingcat has previously reported, Wagner originated in Ukraine back in 2014. This private military contractor has risen to newfound prominence following Russia’s full-scale invasion of the country in February 2022, most recently amid the fierce battle for Bakhmut in eastern Ukraine.

Extensive news reporting in recent years has illustrated Wagner’s operations not only in Ukraine but also in Syria, the Central African Republic, Libya, and Madagascar, among other countries. In January, the US Treasury went as far as to label Wagner a “transnational criminal group”.

As analysts from the Carnegie Centre put it in 2019, Wagner’s usefulness lies in the fact that it can do, or claims it can do, what the Russian state and its formal institutions can’t. It is “a vehicle the Kremlin uses to recruit, train, and deploy mercenaries, either to fight wars or to provide security and training to friendly regimes.”

“It is quite clear from the preparatory work that went into building the Wagner Group’s profile ahead of the February 2022 invasion that [Russian President] Putin counted on being able to use the Wagner Group to fill gaps in Russian military units”, said Candace Rondeaux, a Professor of Practice at the School of Politics and Global Studies at Arizona State University, in an interview with Bellingcat. “All the evidence has long pointed to close coordination between the Wagner Group’s leadership and both the GRU and FSB [Russia’s security services]” added Rondeaux, who has researched the Wagner group in depth in a series of reports.

Due to Wagner’s secretive nature, it can be difficult to verify the number of fighters it commands, As of January 2023 estimates by the US and British ministries of defence ran to at least 50,000, convicts or not. The head of Russia Behind Bars, an NGO which protects the rights of prisoners, says that figure is convicts alone. Rondeaux told Bellingcat that she did not find these estimates credible and believes that they are “likely based on the some 30,000 men who are counted as missing or released from prison since the start of the war”.

Whatever the figure, Wagner has grown significantly since its inception. The fact that the group operates openly at all suggests that its usefulness to the state is recognised – although private military contractors are technically illegal under Russian law under Article 359 of the criminal code, in 2018 Russian President Vladimir said that Wagner does not break Russian law.

So Prigozhin’s promises to these prisoners also have a presidential pedigree – Russian presidential Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov admitted on January 27 that Putin is indeed issuing pardons to convicts who fight for Wagner, noting that one of them received a medal from the president for his “heroism” in Ukraine.

Local media reported Wagner recruiters visiting prisons in every corner of Russia – Tyumen, Chelyabinsk, Kemerovo, the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, and many others. RFE/RL’s report from a prison in Primorsky Krai noted that over 100 prisoners are often enlisted in each recruitment trip. Prigozhin has also taken foreign citizens from Russia’s jails; one man from Zambia and one from Tanzania have died while fighting for Wagner in eastern Ukraine. According to news reports, both men were studying in Moscow before being imprisoned for drug offences.

At the Yoshkar Ola prison, Prigozhin noted that Wagner wanted inmates under the age of 50. However, several recruited convicts have well exceeded this limit. Three of them include 59-year-old Sergei Maksimenko, 55-year-old Andrey Berezhnykh, and 55-year-old Igor Kusk.

These three men are notable not just due to their age, but due to the fact that each led violent criminal gangs in the 1990s.

One of the major legitimation strategies for Putin and his enduring political power is his claim of bringing stability to Russia after that tumultuous decade. This plea towards stability helped justify previous military interventions, such as in Chechnya early in Putin’s ascendance, and the country has come full circle – the men who helped create the instability of Russia in the 1990s are fighting, and dying, in Russia’s latest war.

Each of these three former gang leaders tried to fight for a pardon, but instead died in Ukraine. Who were they, and how were their deaths received back home?

The ‘Avenger’: Andrey Berezhnykh

Andrey Berezhnykh giving testimony to Russian authorities. Screenshot from testimony video via MediaZona.

Andrey Berezhnykh was 55 years old when he signed up to fight for Wagner. In 2013, Russia’s supreme court had sentenced Andrey Berezhnykh to 25 years’ imprisonment for murder and a litany of other offences during his leadership of a small gang in the Saratov region from 1994 to 2011. Berezhnykh had also been convicted by a Saratov court the previous year for the attempted murder of 10 other people.

Berezhnykh organised his gang in the mid-90s in Balakovo, about 150 kilometres from the regional capital of Saratov. He continued it for nearly 20 years until he and other gang members were arrested. According to criminal investigators and information Berezhnykh had told them, Berezhnykh was originally a driver for the director of a Balakovo car dealership, whom he befriended. Berezhnykh told producers from the “Honest Detective” television show that he formed his criminal gang after his boss was murdered, desiring to avenge his “close friend’s” death.

As Berezhnykh recollected, the criminal gang soon took on a commercial structure as he recruited more members. It moved into the arms trade – and apparently became trigger-happy. On October 6, 1994, Berezhnykh and his colleague Andrei Kurpach attacked a group of young men leaving a sports hall with semi-automatic rifles, killing three. Berezhnykh and his group committed a number of other murders and attempted others over the years, including against local business owners.

Screenshot from a dramatisation of an attack that killed three young men in 1994, from Russian state television’s “Honest Detective” show, focusing on the crimes of Andrey Berezhnykh. Source: Honest Detective, Russia-1 TV channel on YouTube

In 2003 Berezhnykh’s criminal group admitted to an attack on the Saratov television station STV with, as the Saratov court records note, an RPG-26 grenade launcher. In 2008, he moved from the Saratov region to Moscow, where he reportedly used the last name “Borodich”. According to a report from a Russian crime blog at the time of his arrest, Berezhnykh owned six apartments in Balakovo. Leaked Russian residential databases reviewed by Bellingcat corroborate this claim, showing a number of real estate registrations to his name in 2007 and 2008.

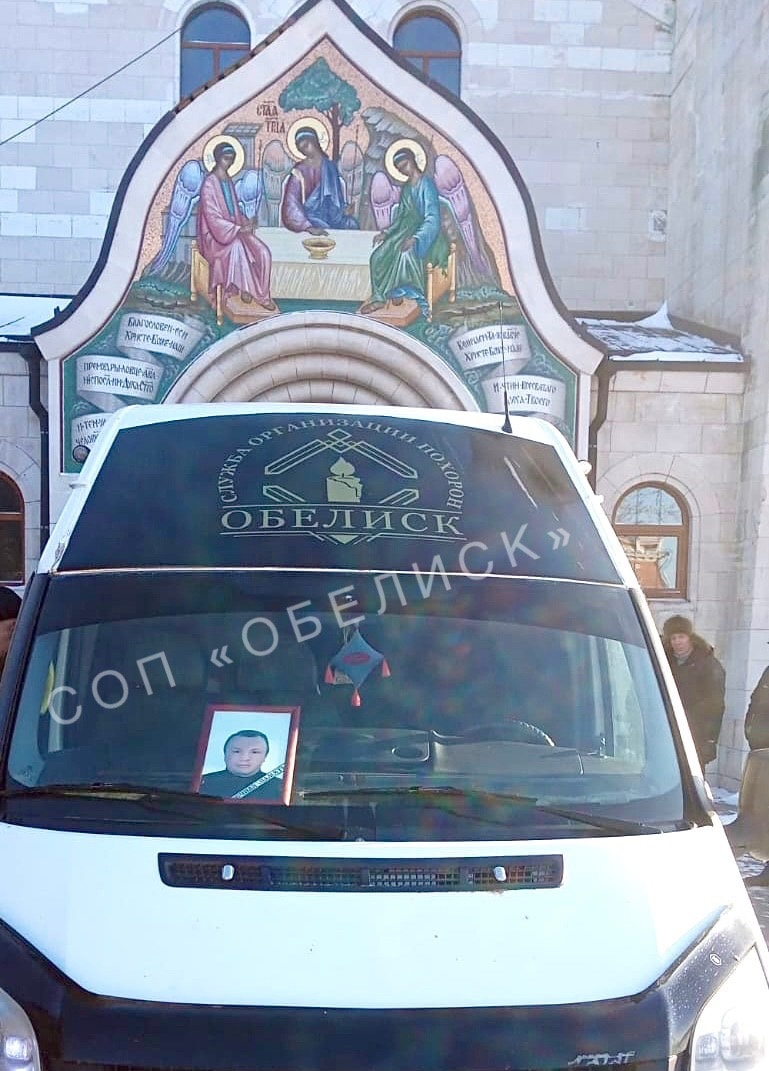

A Telegram channel focusing on Russia’s criminal underworld claims that Berezhnykh died during combat in Ukraine on 8 December 2022, after signing up with Wagner just a month prior. Local news websites from his hometown of Balakovo corroborate these events. A service was arranged for him a month after his death, during Eastern Orthodox Christmas, in Balakovo’s Cathedral of the Holy Trinity. Unlike other Wagner inmates who have died, there was no notable turnout and large attendance for this funeral service. A local funeral service website in Balakovo uploaded photographs of his coffin and service (archived) with no visible attendees, unlike other photographs of Russian servicemen and mercenaries who died in combat.

The reception among Russians hearing of Berezhnykh’s death has been mixed. The regional news website Svobodniye simply describes his biography. Meanwhile Balakovo local news outlet Go64 refers to him as a ‘hero’ – though likely referring to his military service rather than his criminal past, which it does not mention.

Andrey Berezhnykh’s hearse, photographed for his Orthodox Christmas day service.

Source: SOP “Obelisk” / VK

Local news outlet SutyNews described a split among the locals regarding the city’s “most famous inmate.” Comments from Balakovo residents across a number of local interest VK pages mirror this split – one woman wrote, “But can there really be atonement for a person who killed seven people, many of whom were innocent victims? And now he is being buried with honours in the church as a hero.”

Others were somewhat more positive, such as a local woman who wrote that, “He could have served his term further, but he deliberately went to a dangerous place, though with his own motives. Maybe he is not a direct hero in any conventional sense, but he, I think, deserves respect. At least for his choice to stand up for the Fatherland, and not hide, like many.”

The ‘Olympian’: Sergei Maksimenko

Court footage of a number of members of the Olympia gang in Penza. Maksimenko stands in the centre, in a green shirt, behind the glass of the defendants’ booth. Source: GTRK Penza channel on YouTube

Sergei Maksimenko was 59 years old when he signed up with Wagner while serving a 25-year prison sentence in the Mordovia Republic, a region 650 kilometres south-east of Moscow. Russian media reports indicate that he signed up to Wagner in September 2022 – this matches a report from Gulagu.net, a Russian anticorruption and anti-torture watchdog, that Prigozhin visited two Mordovian prison colonies (#7 and #17) on September 17. According to the same site, Prigozhin recruited around 240 prisoners from both prison colonies.

Like Berezhnykh, Maksimenko died in December 2022 while fighting with the private military company in Ukraine. According to public court records, Maksimenko led a criminal group in the city of Penza called “Olympia”, which was active throughout the 1990s and 2000s in activities that include prostitution, extortion, and murder. As the leader of Olympia, Maksimenko was sentenced to 25 years in prison in 2014, the longest punishment of the 13 members who were convicted in Penza.

Maksimenko took control of the Olympia group in 1997. After his arrest, the Penza Press, a local media outlet, described the rise of the group under his leadership and how it established hegemony over other criminal groups, running protection rackets and loanshark operations.

Redacted court documents and the Russian newspaper Kommersant report that in the early 2000s, Olympia carried out a number of murders, largely of local business owners and leaders of rival gangs. Regional Russian authorities have highlighted the especially strict, hierarchical structure that Maksimenko imposed onto the group and the viciousness of their methods; in 2003 its members attacked seven people (“including their wives”) in a local bar with baseball bats and hunting rifles.

The sentences of a number of Olympia members were reduced for a number of reasons, including how they contributed “to the development of sports among children” through the work of the Olympia sports hall.

Like with Berezhnykh, local reception towards the crime boss in his home city of Penza was mixed. Most local media reports have not editorialised Maksimenko’s life or death, instead simply reporting the facts of his biography, criminal past, and death while fighting with Wagner. In contrast, the head editor of the Penza’s “Moskovskaya Street” newspaper wrote an editorial for local site Penza Online praising Maksimenko’s decision, saying that “he retained his daring spirit” by going to fight in his advanced age.

There is little information on the turnout or reception towards Maksimenko’s funeral or burial service, other than the fact that it reportedly took place on January 4th at a cemetery in Penza.

‘The Afghan’: Igor Kusk

Igor Kusk during his court sentencing hearing in 2015. Source: Business Online channel on YouTube

Igor Kusk was 55 years old when he signed up with Wagner while serving a 23-year prison sentence in Syktyvkar, the capital of the Komi Republic, a remote region located about a thousand kilometres northeast of Moscow.

Unlike Berezhnykh and Maksimenko, Kusk, who was a veteran of the Soviet Union’s War in Afghanistan, sought to fight in Ukraine before Wagner visited his prison – his widow told the Russian media outlet Business Gazeta how he sent a letter to Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov to fight in Ukraine. Instead of fighting with a Kadyrov-affiliated group, such as the Akhmat, he was collected by Wagner. It is not known whether the Chechens rejected him or on what grounds.

Kusk’s widow has described how he joined Wagner before being sent “to the front on July 25,” and this is corroborated by reports that Wagner recruited from prison colonies in the Komi Republic in the summer of 2022. In an interview with Vladimir Osechkin of Gulagu.net, a Russian fighter who was captured in Ukraine described how Prigozhin came to visit a prison in Syktyvkar in the summer of 2022 to recruit prisoners to fight with Wagner, promising a high monthly salary and a pardon after 6 months. The Russian investigative website Vazhnye Istorii (“Important Stories”) has reported on the death of a Wagner fighter who was recruited from prison colony 1 in Syktyvkar on 28 July 2022, corroborating the testimony of the prisoner interviewed by Osechkin.

Court documents from his 2015 conviction detail how Igor Kusk started his criminal band, named after himself (“Kuskovskie”, roughly translated as “Kusk’s guys”), in 1998 in Tatarstan, a region about 850 kilometres east of Moscow. His group was particularly active in Nizhnekamsk and the large regional capital of Kazan, home to more than a million people. The Kuskovskie were notable in that they had a number of Afghanistan veterans among their ranks, so many that they were also called “The Afghans”.

Initially, Kusk’s gang operated on the same scale as Berezhnykh and Maksimenko’s outfits: in the late 90s, the Kuskovskie were engaged in similar, relatively low-profile crime and contract killings. According to court documents, their first known murder in 1998 was the contract killing of a local electrician by shooting him outside of his house on the morning of December 30.

But then their appetites and their profile grew. In 2004 Kusk and his group were responsible for the murder of two general directors of the Kazan-based Tatsantekhmontazh construction company, which at its height employed over 1,000 people. The construction company had become enmeshed with the criminal group, and these two murders were, according to Russian prosecutors, related to attempts to the general directors’ attempts to disentangle themselves from the Kuskovskie. General Director Vasily Luzganov was killed in 2001 after firing a high-ranking staff member who was carrying out procurement scams on behalf of the Kuskovskie – his murder was arranged by the criminal group. Prosecutors established that General Director Boris Vaiman was murdered by the Kuskovskie after conducting business that was seen as “contrary to the guidelines” of the criminal group.

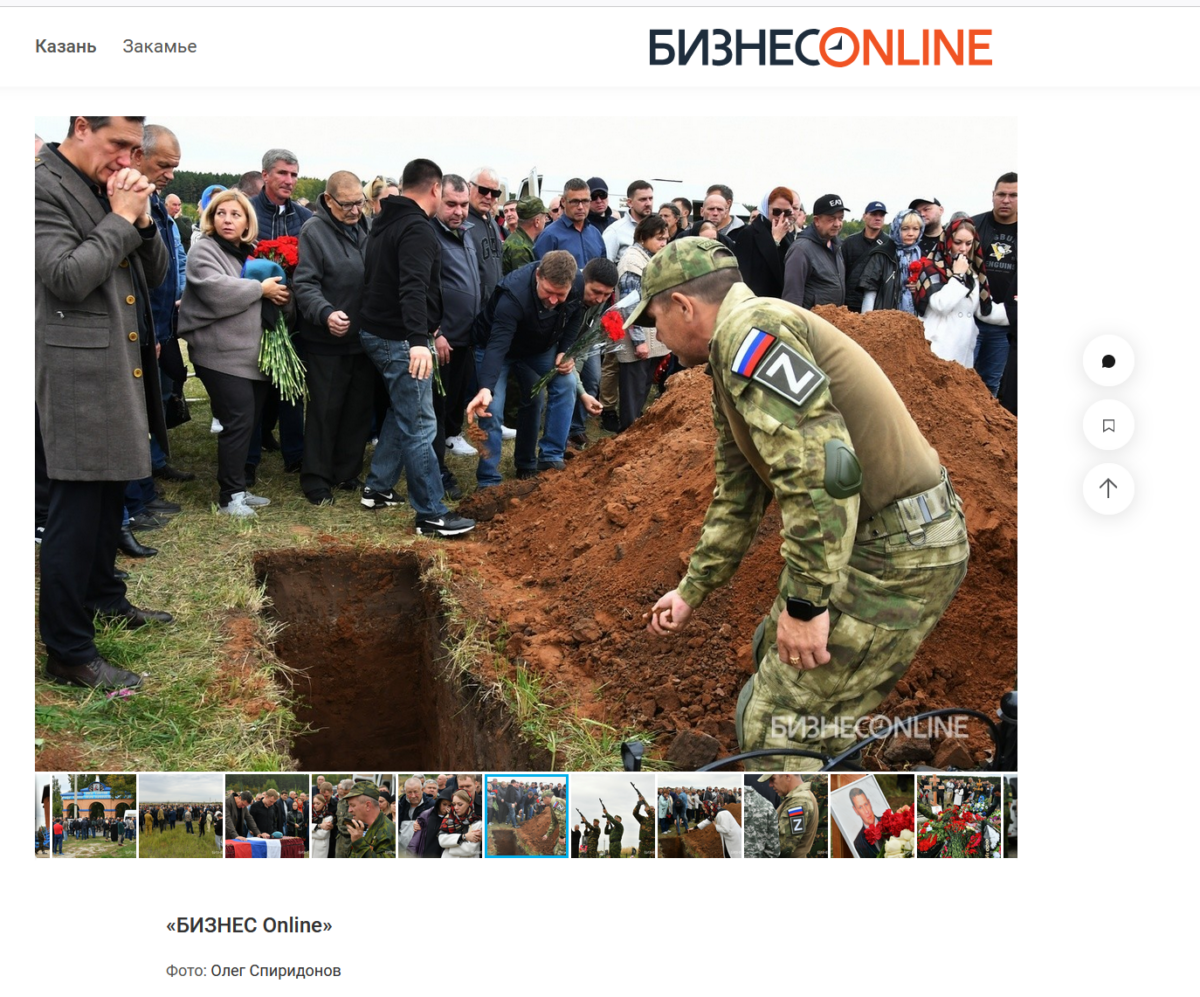

The funerals of 90s crime bosses Berezhnykh and Maksimenko were fairly low-key affairs, with virtually no news of the latter’s burial service and a lightly attended one for the former. Igor Kusk’s burial was a notable event – per the Real New Times media outlet, over 700 people attended the funeral service and burial, with about 100 vehicles in the procession.

Screenshot of a photo gallery on Business Online’s website showing the funeral of Igor Kusk in Nizhnekamsk, Tatarstan

According to independent Russian media outlet Holod, Igor Kusk led Tatarstan veteran communities, which not only gave him popular support that was reflected in his funeral but also a reduced prison sentence. Like Maksimenko, Kusk’s sentence was reduced due to what the court’s saw as charity work for children – his “active participation in the military-patriotic education of youth”.

As a Tatarstan judge said in a 2018 interview with Realnoye Vremya, Kusk “combined this social activity [in veterans’ unions] with a criminal one.” The scene around Kusk’s funeral matched that of his sentencing hearing – Afghan and other military veterans, whom he represented in union organisations, attended both events in support of the former gang leader.

Free at Last

The mixed public reception to the deaths of Maksimenko and Berezhnykh may simply be because their heydays are past – a new generation of criminals succeeded them.

Many of the other convicts who joined Wagner are reportedly some of the most violent and undesirable elements of more contemporary society, with convictions far more recent than the three men profiled here. Among them are a man convicted in 2017 of beating his own mother to death, a man convicted in 2017 of murdering two women by stabbing and strangulation, and a man who in 2012 bludgeoned his neighbour to death with a fire iron.

It is still an open question as to how many of these inmates will achieve their desired pardons. Two dozen inmates-turned-Wagner-fighters were reportedly pardoned in a public ceremony led by Prigozhin.

However, there have also been reports of Wagner fighters having their contracts extended without their consent. In the coming months it will become clear how real the fulfillment of the promised pardons will be as the first wave of prisoners who were recruited in the summer of 2022 reach the end of their six-month term.

Prigozhin, who is himself reportedly an ex-convict, has stepped up for former criminals fighting in Ukraine. If they ever got in trouble with law enforcement after their release, he told a group of pardoned veterans, they should give him a call. “They should treat you with respect”, he stressed.

Accordingly, in a letter addressed to the speaker of Russia’s State Duma Vyacheslav Volodin on January 24, Prigozhin called for a ban on ‘discrediting’ former convicts who had fought in Ukraine, defined as “publications of a negative character or any information about their previous convictions”.

Offenders could face up to five years’ imprisonment.