On January 31, the Rahmanis filed a lawsuit against the U.S. government in response. In the suit, they “categorically deny any involvement in any fuel procurement corruption scheme.” The court partly rejected their challenge in April.

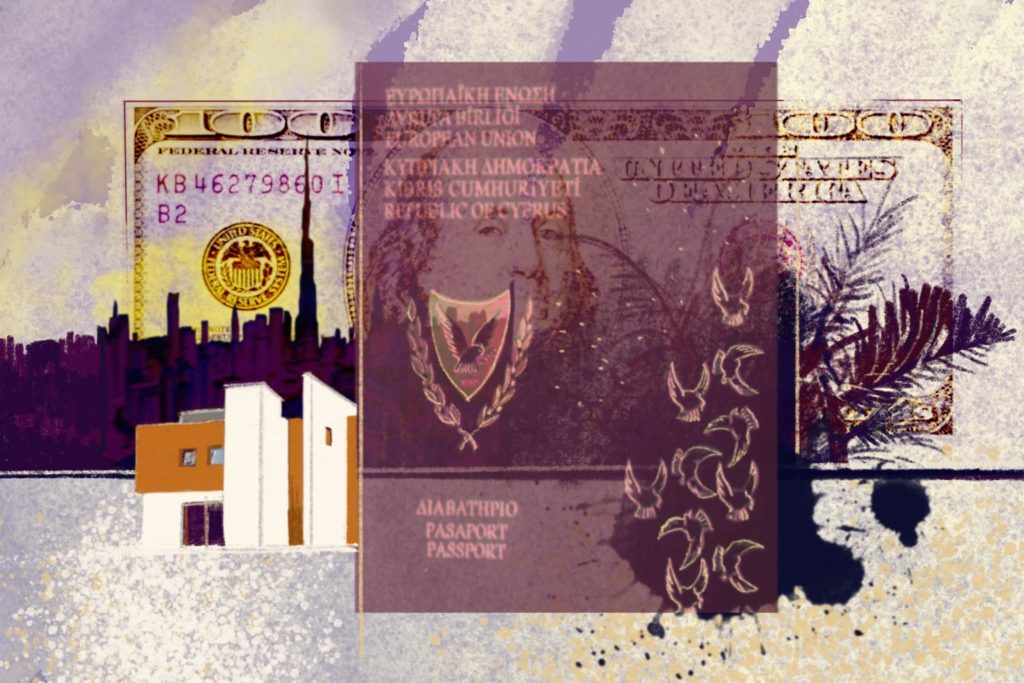

The Rahmanis’ lawsuit revealed that they were still holding Cypriot citizenship, even though both were assessed in 2021 as high risk by the Nicolatos Committee, which investigated corruption in Cyprus’s golden passports scheme. The ad hoc committee – appointed by Cyprus’s attorney-general and led by former Supreme Court president Myron Nicolatos – recommended that the passports be reviewed for revocation.

The committee cited a letter by financial intelligence unit MOKAS, which flagged a reference to Mir Rahmani’s alleged connections to an Islamic group and political party Jamiat-e Islami, identified by a Cypriot bank during a due diligence process for a company bank account application. The committee also cited Rahmani’s failure to disclose his political party affiliation, and questioned the authenticity of the paperwork for his family members.

“No credible authorities or legal bodies have brought such accusations against me or my dependents,” Mir Rahmani said in an email. “All business transactions conducted in Cyprus have been lawful, fully transparent, reported to all relevant authorities, and strictly following international standards and regulations.” He also denied any affiliation with Jamiat-e Islami.

The Ministry of Interior has confirmed that the Council of Ministers has revoked the citizenship of 233 individuals, of which 68 were investors and 165 were their family members – the same total confirmed in November 2023. The names of individuals are not made public, the Ministry said, citing privacy protections. It also declined to comment specifically about the Rahmanis’ passports but added that revocations are only applicable for EU and UN sanctions, not by “third countries.”

Ajmal Rahmani stated in the lawsuit against the U.S. government the importance of his Cypriot passport, noting that he obtained citizenship by “investment from Cyprus, and began investing in Europe” and that “his [UAE] residency is tied to his Cypriot citizenship.”

The Rahmanis added that the sanctions are “exposing them to serious risk of loss of citizenships, potential deportation to Afghanistan where they and their families, if returned, would encounter serious threat and risk of persecution and physical harm at the hands of the Taliban.”

Reporters from ZDF frontal and OCCRP – in collaboration with CIReN – have now uncovered a large real estate portfolio – worth over €200 million – amassed by Ajmal Rahmani, much of it registered to his Cypriot passport. Mir Rahmani owns €680,000 worth of property in Dubai, though it’s unclear which passport he used.

International Investments

In Dubai, Ajmal Rahmani owns at least five properties worth an estimated €2.9 million, which were registered to his Cypriot passport. Another 16 properties and two multi-unit residential buildings developed by Ocean Estate Company Limited and Fern Limited – Emirati companies set up by Ajmal Rahmani and sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury – are estimated to generate an annual rental income of €1.8 million.

In Germany, he purchased some €197 million worth of real estate, using Cypriot holding companies, and German companies registered to his Cypriot passport.

When asked about reports that prosecutors in the German city of Stuttgart were looking into real estate transactions related to his businesses, Ajmal Rahmani said in an email that he and his colleagues “are actively cooperating with the Stuttgart Public Prosecutor’s Office through our legal representatives to support their preliminary examinations.”

Cypriot citizenship also helped Tahmina Tajali, the wife of Ajmal Rahmani, purchase a property in the Austrian ski resort town of Kitzbühel in 2020. Property records show the chalet, which cost €10.5 million, is registered to her Cyprus passport.

Austrian regulations require people from countries outside the EU to obtain approval from local authorities before buying a property, which is granted only if there is a cultural, social or economic interest in concluding the transaction and the purchase will not impair “national political interests.”

Beachside in Cyprus

To obtain his Cypriot passport, Ajmal Rahmani purchased a villa in August 2014 in the coastal town of Agia Napa.

According to the U.S. Treasury press release, this was the same year the Rahmanis had “colluded to drive up the price of fuel on US-funded contracts by more than $200 million.” The Rahmanis “categorically deny” the allegations in their lawsuit challenging the sanctions.

“Our legal team is prepared and has substantial evidence proving that the referenced $200 million fuel corruption allegation is unfounded and not linked to us or any of our affiliated companies,” Ajmal Rahmani added in an email to reporters.

His father denied any involvement in the fuel business. “I have neither held any fuel contracts nor conducted business of this nature with the US, NATO, nor any type of contract with Afghan governments,” Mir Rahmani wrote in a separate email.

A purchase agreement obtained by the Nicolatos Committee states that Ajmal Rahmani paid €2.5 million for the beachfront villa – the minimum required investment under the citizenship-by-investment scheme at the time – plus 19 percent VAT, for a total of €2,975,000.

According to leaked invoices, Rahmani also paid €55,000 in fees to Henley Estates, a local broker for the global company Henley & Partners, and according to the Nicolatos report, another €90,000 to FidesCorp Limited, the Cypriot service provider co-owned by the ex son-in-law of Demetris Syllouris, a former Cypriot House speaker now facing corruption charges in connection with the passport scheme. There is no suggestion that Syllouris or his ex son-in-law did anything illegal in regard to the Rahmanis passport applications.

In an emailed response to questions, Henley & Partners spokesperson Sarah Nicklin said its finance department had “done a thorough check and cannot locate any payment received from Rahman Rahmani and/or his son Ajmal Rahmani.”

“However, it could be that these individuals were referred to independent local service providers, and that Henley Estates was involved in the associated real estate purchase,” Nicklin added.

“Henley Estates never processed citizenship applications but was a real estate business which was being acquired by Henley & Partners, and therefore our firm was neither responsible for the application processing nor for the real estate transactions of these individuals,” Nicklin said.

The leaked invoice stated that Henley Estates billed Ajmal Rahmani on behalf of Henley & Partners for “Citizenship Application Fees.”

FidesCorp did not respond to questions.

As it turns out, financial fugitive Jho Low purchased his own luxury villa for €5 million in the same area as Rahmani, and used the same providers to help obtain his Cypriot passport. But Low’s passport was reportedly revoked by Cypriot authorities last year, almost four years after an initial investigation.

A confidential report by a separate ad hoc committee, headed by then chair of the Cyprus Securities and Exchange Commission Demetra Kalogerou, noted that in November 2019 the government planned to revoke Low’s passport, adding that the applicant had “disclosed very limited information on corporate holdings” and that he had “Interpol red notices issued around the same period that citizenship was granted.”

While Cyprus canceled its citizenship-by-investment scheme in 2020 after the government acknowledged it was flawed, its legacy continues to plague the island’s reputation.

“Golden passports attract unsavory characters for many reasons,” said Eka Rostomashvili, advocacy and campaigns coordinator at the Transparency International Secretariat. “In addition to increased mobility, being a citizen of an EU member state brings certain privileges. Among them is less scrutiny when opening a bank account or a company, which can be exploited for shady deals or criminal activity.”