The Guardian: As a Spanish reporter, Pablo González charmed his way into Russian opposition circles and covered Putin’s wars. Then, in 2022, he was arrested on suspicion of espionage. Many former associates now believe that he betrayed them.

One afternoon in March 2014, while reporting on Russia’s covert operation to annex Crimea, I spotted a familiar figure. With his muscular build and shiny shaved head, Pablo González was easy to recognise from afar. I had first met González, a freelance journalist from the Basque Country, on a training course for reporters who work in conflict zones. Now we had run into each other in a place that was threatening to turn into one.

González was with a Ukrainian journalist, who had contacts at the besieged military base I was on my way to scope out. He arranged for the three of us to slip inside, where we found a detachment of Ukrainian marines on edge. Outside, an angry crowd of locals was yelling pro-Russian slogans, but these people were just cover for the Russian army, the marines said. They were expecting an imminent visit from a Russian general, and agreed that we could leave a Dictaphone on the base, for them to covertly record the conversation.

Some time later, I received audio of the emotional encounter that followed, in which a man identifying himself as a senior general in the Russian army gave the marines an ultimatum to surrender, prompting furious protests. The recording was hard evidence that Vladimir Putin’s denials of Moscow’s coordinating role in Crimea were nonsense. It felt like listening to a piece of history unfold in real time – the first forceful annexation of land in 21st-century Europe. I was grateful to González for helping me get the story, but after that day I never saw him again.

Eight years later, in the early hours of 28 February 2022, González was arrested in the Polish city of Przemyśl. It was a few days after the start of the latest and most brutal episode in Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the first moments of which we had witnessed back on the Crimean base. A terse statement from Polish authorities said that González was suspected of “participation in the activities of a foreign intelligence service”. They claimed he was an agent of the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency. He faced up to 10 years in prison.

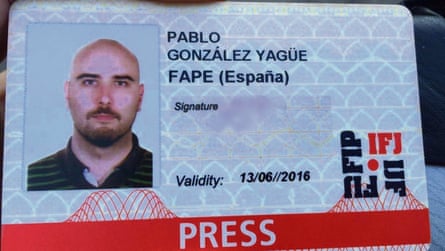

At the time, the story barely registered, given that Russian troops were bearing down on Kyiv. But a few months later, a claim about González caught my attention. Richard Moore, the head of Britain’s MI6 foreign intelligence service, used a rare public appearance to announce that González had only been “masquerading as a Spanish journalist”. In reality, claimed Moore, he was a so-called “illegal” – a deep-cover Russian spy, usually one who appropriates a foreign identity for long-term missions abroad. Illegals typically spend years in training to convincingly impersonate foreigners. Polish authorities believed Pablo was really Pavel, and had been born in Moscow.

I have been fascinated by Russian illegals for years, and have even written a book about the history of the programme. Now it turned out that I may have crossed paths with one in the field, without suspecting a thing. Perhaps, on that day at the Crimean base, González had been carrying out other tasks besides journalism. But friends and colleagues from Spain were not convinced by the MI6 chief’s claim. Far from disguising his Russian background, they said, González had never denied he was of Russian origin. Among friends at home in the Basque Country, he was widely known as Pavel, or “the Russian”.

Two years passed after the arrest. Poland released no evidence to the public, and no date was set for a trial. Had the Poles pounced on an innocent journalist, misinterpreting his Russian roots as something more sinister? González’s Spanish wife, Oihana Goiriena, claimed his prolonged detention was aimed at breaking him. “Our hypothesis is that, in the absence of evidence, they want to destroy him morally and emotionally so that he signs whatever they put in front of him,” she told a Spanish journalist after a rare prison visit to see the father of her three children.

Then, in August 2024, the biggest prisoner exchange between Russia and the west since the end of the cold war got under way at Ankara airport in Turkey. Russia freed a group of political prisoners, as well as several high-profile foreign detainees held in Russian jails, including the Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich. In return, a number of Russians detained in the west headed back home. A government plane picked them up in Ankara, and television crews were standing by when the plane landed in Moscow. On the tarmac, Putin was waiting. A guard of honour stood either side of a red carpet, for the returnees’ first steps back on Russian soil.

Out came Vadim Krasikov, convicted of murdering a Chechen dissident in a Berlin park. Then came a husband and wife illegal team arrested in Slovenia, who had spent more than a decade abroad posing as Argentinians. They walked down the steps towards Putin with their two young children, who had only just found out they were actually Russians. Next came a tall, bald and bearded man wearing a Star Wars T-shirt emblazoned with “Your Empire Needs You”. It was Pablo González.

Putin gathered the returnees inside the airport terminal building. Addressing those in the group who had been sent abroad on official service, he said: “You will all receive state awards, and we will see each other again to talk about your future. For now, I just want to congratulate you on your return home.”

For some of González’s most ardent supporters, this was the moment their convictions about his innocence crumbled. “For the last two years I was always defending Pablo, saying that he needs a proper free and open trial,” one friend, a fellow reporter, told me. “But you’d have to be pretty naive to think that Russia goes around the world rescuing journalists. I think with this handshake [with Putin], he is proven guilty.”

Other friends are still convinced of his innocence, and from Moscow, González denies he ever had any links to Russian intelligence, according to his Spanish lawyer, Gonzalo Boye, who still speaks to him by phone regularly. Boye told me the fact that Poland held González in pre-trial detention for more than two years without ever putting him in front of a judge was proof the case was flawed. “If you have a crystal clear case of espionage, present the charges and let’s go to trial,” he said. “Since when in Europe can something be handled in this way?”

In the weeks since the prisoner exchange, I have interviewed dozens of people who knew González in Europe and in Russia. I have also met with current and former security and intelligence officials in Poland and Ukraine, spoken to those familiar with the Polish evidence against him, and investigated his family history. I hoped to answer some of the questions that those who knew González were now turning over in their heads. Was there any chance at all he was an innocent journalist, wrongly accused? Or if he really was a Russian spy, when was he recruited? What were his motivations? And how much damage did he do?

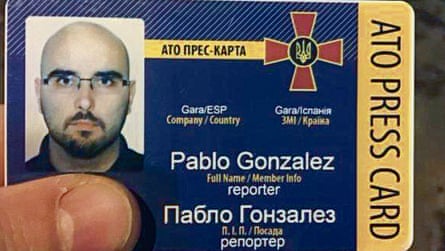

Ifirst met González in 2011, on a week-long training course for journalists in the Welsh countryside. As I pieced together his life story, I realised it had been a key year for him. He started to write his first newspaper articles for Gara, a small leftist newspaper published in the Basque Country. He married his Spanish girlfriend in a ceremony in the town of Guernica. And then in November, he headed to Wales.

The course, which is run by former British army officers, aims to equip journalists with the skills to survive in war zones. There is an invaluable first aid component, as well as a role-play element of more dubious value. Back in 2011, we were told to imagine the back roads of rural Wales were in fact deepest Peru. A few minutes after setting off on a “reporting assignment”, our fleet of Jeeps was pulled over by two men in bandanas, screaming furiously and waving automatic rifles. They were revolutionaries from the Shining Path, one of them said, and we would probably all be shot.

As we were marched at gunpoint through the woods, instead of going along with the captors’ demands, González furiously berated them. Eventually, he managed to persuade our kidnappers to release us all. “Wow, this guy is a hero,” James Brown, who went on to have a career in international aid work, remembered thinking at the time. “But is this the way we’re meant to be responding?” He realised that the line between being a hero and a liability was a fine one, and he couldn’t decide on which side of it González’s actions landed.

González introduced himself to us as a Spanish freelancer; when I contacted others from the course, nobody could remember whether he had mentioned any Russian roots. But I do recall that he was a passionate and funny storyteller during the long and boozy evenings we spent at the hotel bar. I have a strong memory of him pulling himself up by a wooden frame suspended above the counter one evening, and thrusting his hips vigorously in mid-air, to illustrate some anecdote or other. Later that night, there was a furious argument with a Fox News correspondent, the subject of which is long forgotten.

These stories – the kidnap heroics and the drunken hi jinx – chimed with many stories about González I would hear from people who encountered him over the next decade. In some, he came across as a heavy-drinking buffoon; in others, he was a charming presence, skilled at forging friendships and making high-level professional connections, despite working for small Spanish outlets. He frequently reported from war zones, and sometimes showed real bravery. Once, during a shelling attack in Nagorno-Karabakh, he even helped bring two severely wounded French journalists to safety.

I don’t know if González was already being prepared for life as a spy back in Wales in 2011, or when we met in Crimea in 2014. But by 2016, the Polish case files allege, he was very much active, using his job as a journalist as cover to get access to some of the Kremlin’s biggest enemies.

Zhanna Nemtsova was 30 when her father was murdered in 2015. Boris Nemtsov, one of Putin’s most persistent critics, was shot four times in the back from a passing car while he was walking home through central Moscow, late one evening in February 2015. A few months later, after receiving threats herself, Nemtsova decided to leave Russia. From exile, she set up a foundation in her father’s name, with the goal of supporting independent media and political activism in Russia. In January 2016, she was in Strasbourg for a meeting that called on the Council of Europe’s parliamentary assembly to appoint a special rapporteur to investigate her father’s murder. It was a largely symbolic move, but in the absence of a proper investigation by Russian authorities, it was at least something.

During a break in proceedings, Nemtsova was approached by a tall, confident man speaking lightly accented Russian. He told her his name was Pablo González, and said he worked for Gara, a newspaper in the Basque Country. Would she grant him an interview? Nemtsova politely declined; she had never heard of Gara and had a packed schedule. But González did not give up easily. He persuaded a friend of Nemtsova’s to put in a good word for him and in the end, she agreed to the interview. “I don’t remember any of the questions, which shows it was nothing unusual,” Nemtsova told me recently.

After their first meeting, Nemtsova put González on the mailing list for the foundation’s public events. He always came, and gradually got to know her better. She found him funny and easy-going. At some point, their relationship took a romantic turn. Through Nemtsova and her associates, González met many other Russian dissidents. The annual Boris Nemtsov Forum was one of the few platforms where the fragmented exiled opposition, as well as the shrinking number of Kremlin opponents still based inside Russia, gathered in one place. González came, too; to Madrid, Berlin and Warsaw, depending on the year.

As I called around different contacts in the Russian opposition, I was struck by just how many of them had met González. They described him as a flirty, chatty and warm character who was always up for a beer or six. He was meticulous about staying in touch, and he often acted as tour guide for his new Russian friends on visits to Spain. For one group of Russian exiles, he offered a tour of the Basque Country, taking them to an atmospheric lunch club in a village not far from his home, where he seemed to know everyone. Ilya Yashin, who had been one of Boris Nemtsov’s closest associates, recalled meeting up with González on a trip to Madrid and going together to an Atlético match. Yashin mentioned he needed a new coat, so afterwards González took him shopping.

González would tell his new Russian friends that he was married with children, but he said the relationship with his wife had long broken down and that now they were more like friends. Although he mentioned having some Russian heritage, he allegedly said he had not been to Russia since childhood and even asked his Russian opposition contacts for advice on how to get a visa. If any of them had Googled his journalism, they would have found articles written for Gara from Moscow. They might also have found appearances on the Kremlin-backed channel Russia Today, one of which he used to accuse Ukraine’s pro-western government of paying a Spanish newspaper for favourable coverage.

But nobody was doing background checks. “He was in this circle of opposition journalists and activists,” said Pavel Elizarov, a political activist and former associate of Nemtsova’s. “We don’t need to discuss Putin’s politics because we all know we are on the same page.”

If people encountered something about González that struck them as odd, they often attributed it to his Basque background. Nemtsova soon realised that he had a different view of the world to her, but she put it down to the specifics of southern European leftism, and decided simply to stop discussing politics when they met. With others, González often voiced his support for the so-called “people’s republics” in eastern Ukraine, which Moscow was propping up financially and militarily. But they found it natural that someone of Basque origin would sympathise with separatist movements.

Volodymyr Ariev, a Ukrainian MP, was surprised when González showed up to their first interview, at his office in Kyiv in 2015, brandishing a bottle of wine as a gift. “He said it was from his home region,” Ariyev remembered. “I had never met a journalist who brings a present to a meeting before, but I thought it was probably some kind of Basque tradition.” The interview itself was unremarkable, and afterwards González made small talk about the politician’s family, travels and hobbies. It was standard behaviour for a journalist trying to befriend a new source, though years later, after the arrest, Ariyev wondered if it might have been an attempt to psychologically profile him.

In late 2017, González signed up for a five-day training course run by Bellingcat, an influential group of open-source investigators who had done impressive work to prove Russian complicity in the shooting down of a Malaysian Airlines plane over east Ukraine in 2014. The course allowed González to meet many of the people working on Bellingcat investigations, including the group’s founder, Eliot Higgins. Some of the other participants would have been of interest to Russian intelligence, too: they included journalists from leading publications, as well as a senior executive of a tech company that would later sign a contract with a US government department worth hundreds of millions of dollars. At nightly dinners and drinks, González regaled the others with war stories from eastern Ukraine, where he still travelled regularly.

González also continued to stay close to the Russian opposition, and in 2018 he went back to Strasbourg, where Alexei Navalny – Putin’s most high-profile critic – was on a rare visit outside Russia, to speak at the European court of human rights. After the hearing, Navalny and a few others went for drinks at the home of one of the lawyers. It was a friends-only gathering, but somehow González made the cut.

Among the group that evening was a fearless lawyer named Vadim Prokhorov. He was still based in Russia, but flew into Europe regularly for major events. When he first encountered the bulky González, shaven-headed and speaking nearly perfect Russian, his first association was with the sketchy backstreets of a rough Moscow neighbourhood. “What kind of Basque is this? A Basque from Mar’ino,” he joked, referencing the gritty suburb of Moscow where Navalny lived. From then on, Prokhorov always called González “the Basque from Mar’ino”, but González used his trademark charm to ensure the gentle ribbing never morphed into genuine suspicion. “How you drink, how you socialise is very important for Russians,” Prokhorov told me, recalling those meetings. “I don’t think a sober guy would have made it into the group. But Pablo was always the guy who’d drink, the guy who’d run out to get extra booze, tell jokes. He fit in perfectly. You have to admit, he was pretty good at that.”

Some time in 2019, González’s Russian friends started to detect a change in his personality. Nemtsova told me she felt there were two different Pablos. “One was this charming, easy-going guy. ‘Let’s have a party.’ The other was very rude, and always wanted to say he was better than me. He was moody and aggressive. He didn’t bother controlling himself,” she said.

As their on-off relations disintegrated, Nemtsova began to ask herself some questions. Here was a freelancer writing columns for fairly small Spanish outlets, yet he seemed to have the money for constant travel and all the latest gadgets. It reminded her of a phenomenon she knew well from her former life in Russia: the person who lives above their means, the humble bureaucrat with the mansion and the fancy car. In Russia, it was a fairly clear indicator of corruption. But what could it mean in Europe? A possible answer dawned on her.

Each summer, Nemtsova organised a journalism summer school in Prague. González gave a lecture there in 2018, about reporting from conflict zones, and he came again in 2019. That year, Nemtsova recalled, she shared her growing suspicions about González with another speaker, the Russian journalist Andrei Soldatov, who is one of the world’s leading experts on the Russian intelligence services. Could González perhaps be a Russian operative, sent to spy on them? Soldatov dismissed the suggestion as unlikely, she said. (Soldatov disputed this account, claiming the encounter happened in 2018, and that he evaded Nemtsova’s question as he had met González that day for the first time, only spoken to him briefly, and believed the question was motivated by Nemtsova and González’s personal tensions.)

The doubts continued to niggle at Nemtsova. Why did this Basque freelancer have so much money? Why did he speak such good Russian? And why was he so interested in the Russian opposition?

Russian illegals traditionally spend years studying language and etiquette, before setting out abroad disguised as foreigners. But “Pablo González” was not a cover identity crafted with painstaking care under the watch of the GRU. It was real, although its owner had another, Russian name too. The two different identities were the product of a mixed heritage, with its origins in the upheaval of the Spanish civil war.

González’s grandfather, Andrés González Yagüe, was among more than 30,000 children evacuated from Spain to save them from the ravages of the conflict. Most ended up in temporary foster homes in France, Belgium and elsewhere in Europe, but the ship that left in 1937 with eight-year-old Andrés on board was bound for the Soviet Union. Authorities there planned that the arriving Spanish children would be inducted into the ways of Marxism in special institutions, and when the civil war was over, they would return to newly communist Spain, well prepared to form the backbone of a new political elite. Andrés ended up in a boarding house at Obninsk, outside Moscow. In 1939, Francisco Franco’s Nationalists won the civil war, and Moscow decided it would not return the children. Most became Soviet citizens.

Andrés gained a technical education and found work at ZiL, a huge automobile factory in the suburbs of Moscow. He married a Russian woman, Galina, and the couple had two children, Elena and Andrés Jr. In 1980, Elena married a young scientist, Alexei Rubtsov, and their son Pavel was born two years later. By the end of the decade, the Soviet Union was heading towards collapse, and so was Alexei and Elena’s marriage. In 1991, Elena left with Pavel for Spain, taking advantage of their Spanish heritage to obtain citizenship. Elena decided her son should take the maternal family surname on his new documents, and she used the Spanish form of his first name. So it was that Pavel Rubtsov became Pablo González Yagüe.

After finishing high school in Barcelona, González went on to study Slavic philology at university in Spain. Later, he began to idealise his childhood in the Soviet Union. “I was a tremendously happy child there, and no one is going to convince me otherwise,” he wrote many years later in a newspaper column, painting the late Soviet Union as a place of prosperity and plenty. In 2004, he acquired a Russian passport under his old name, Pavel Rubtsov. By now, his father was working in a management job at RBC, a media holding company in Moscow. González, or Rubtsov, visited regularly, even doing occasional bits of work for RBC under his father’s watch. “I remember that Pavel was pro-Russian, pro-Putin, but not with any fanaticism. He just seemed fascinated by Russia,” recalled a source who knew both father and son well.

Some Spanish media outlets have speculated that the key to González’s alleged GRU links could lie with his father. Intelligence affiliations in Russia are indeed often a family matter, but the source who knew the family was sceptical: “Alexei is a patriotic guy. He was a scientist in the Soviet period and feels the country lost a lot during the collapse. But I never saw anything to suggest he had some other work or any connection to the services.” He described Alexei as a quiet, unassuming person who seemed to be the passive partner in the relationship with his second wife, Tatyana Dobrenko, González’s stepmother, who worked in the oil industry. “She was in charge of everything,” said the source.

To double-check Alexei’s background, I called up Christo Grozev, who was previously the lead Russia investigator at Bellingcat, and now works for an outlet called the Insider. Grozev is a prolific spy hunter, busting the cover of numerous Russian operatives over the years, and was recently told by Austrian authorities that he should leave his home in Vienna, as he is under threat from Russian assassins.

Grozev told me he was already looking into González’s Russian family, and later shared his preliminary findings with me. He checked González’s father for all the telltale signs of GRU affiliation – suspicious passport numbers, signs of false identities and official registration at addresses known to be linked to the GRU. The search came back clean. But on the off-chance, he also decided to take a look at Dobrenko, Alexei’s wife. And here, he started to find things that seemed strange.

To start with, there were records for two different Tatyana Dobrenkos, one born in 1954 and one in 1959, yet both linked to the same social security number. Even more curious were her official addresses over time. Prior to the apartment where González’s father lived, she was registered at 76 Khoroshevskoye Shosse, said Grozev. That address, in north-east Moscow, is home to a Soviet-era apartment block that is unremarkable except for one thing: the hulking building right next to it, at 76B. The building is commonly known as the Aquarium, and houses the headquarters of the GRU. “This alone does not prove affiliation with the GRU,” Grozev told me. “But we do see it is also the home address of other known GRU officials.” It was certainly a striking coincidence for someone whose stepson was now accused of being a GRU officer. I sent Dobrenko a message on Telegram asking for comment on these records. She read it, then blocked me without replying.

There was one more suspicious piece of evidence. Last year, the exiled Russian investigative outlet Agentstvo published a story based on a leaked database of Russian flight bookings. One of the bookings appeared to show that in June 2017, two return tickets from Moscow to St Petersburg had been bought in a single transaction: one for González, using his Russian passport, and one for a man named Sergei Turbin. There is strong evidence, according to Agentstvo, that Turbin is a GRU officer. Grozev concurred, noting his research shows he was employed by the GRU’s Fifth Department, which handles illegals. Turbin could not be reached for comment.

In short, during the same period when González had been telling Nemtsova’s associates that he was struggling to get a visa to Russia, he was apparently flying from Moscow to St Petersburg with an alleged GRU officer. I asked his lawyer, Boye, to comment on the trip. “I have no idea,” he said, irritably. “Do you know the people who were sitting next to you on your last flight? Can you guarantee that none of them have criminal records?” I pointed out that both tickets appear to have been bought in the same transaction. Did González know Turbin? Was he on the plane? Boye promised to ask González. A few days later, he told me his client had decided not to answer my questions.

In 2019, González began dating a Polish freelance journalist and late that year he moved to Warsaw, where the couple rented a flat together. From Warsaw, he made frequent trips home to the Basque Country to see his children, and regular reporting trips to Ukraine and elsewhere. He secured several high-profile interviews with figures who would have been of interest to the GRU, including the pro-western president of Armenia, Nikol Pashinyan, and Pavel Latushka, one of the leaders of the Belarusian opposition in exile, and a sworn enemy of the pro-Moscow Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko.

It was not until early February 2022 that the net began closing in. With American and British warnings in the air that Russia was about to launch a major assault on Ukraine, González had travelled with two other Spanish freelancers to Avdiivka, right on the frontline. There, he was apprehended by Ukrainian police and told to report for questioning in Kyiv, where he was interrogated for several hours. The officers demanded access to his mobile phone and accused him of being a Russian spy, but it did not seem they had anything concrete on him. He was advised to leave the country immediately, but not arrested.

In the following days, Spanish intelligence officers visited some of González’s friends and family back home, questioning them about his background. González was furious when he found out. “They have gone to everyone with the same song, presenting me as a pig who uses everyone as a cover. It doesn’t make any sense,” he said in a voice note he sent to a friend at the time. The Ukrainians were asking him about his Russian relatives as if it were a secret, he said, when he had never tried to hide his Russian background. That was true, to a point: his Spanish friends knew he travelled to Russia regularly, but his friends in the Russian opposition did not. The basics of González’s Russian origin story were genuine, but the specifics seemed to shift, depending on the situation.

González returned to Spain, but when news broke on the morning of 24 February that the full-scale invasion of Ukraine had begun, he immediately booked a flight to Warsaw. Before long he was in Przemyśl, the border city through which hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugees were streaming into Poland. He recorded regular live reports for Spanish television channels and news websites. Late in the evening of 27 February, he returned to the dormitory where he was staying, and a few minutes after midnight there was a knock at the door. Green-clad agents of the ABW, Poland’s domestic security service, entered and informed him he was under arrest.

The initial tip-off regarding Pablo González came from an allied intelligence service, but it was incomplete. “It was not the case that we had all the evidence and just had to arrest the guy,” Stanisław Żaryn, national security advisor to Poland’s president, told me. “It was clear from the beginning that this investigation was really big and we would have to dig a lot to see the whole agenda.”

At the heart of the Polish prosecutors’ case is a series of reports that González allegedly wrote over a number of years, apparently to his supervisors in the GRU. “These were typical intelligence reports about facilities, infrastructure and people to be in touch with,” Żaryn told me. Another source said these reports frequently reference “the Centre”, Russian spy code for intelligence headquarters. Some of the reports are understood to have included follow-up questions, apparently from a handler. In one from 2018, González allegedly wrote to his supervisors that he had “destroyed the electronic devices as ordered”, smashing them into pieces and tossing them in the ocean.

Several sources familiar with the Polish evidence against González told me that it includes numerous reports on his contacts in the Russian opposition. Some were mundane, like the account of the day when González took Ilya Yashin to the football. Others allegedly included sensitive information, such as the home addresses of employees of Zhanna Nemtsova’s foundation. One report even allegedly contained copies of personal emails written by Nemtsova’s murdered father. Nemtsova is not allowed to talk about the case, as she is cooperating with the investigation and has signed a non-disclosure agreement, but she confirmed that she possessed Boris Nemtsov’s old personal laptop, brought from Moscow by his lawyer. She also recalled that she had lent it to González on one occasion, when he claimed his own computer had broken.

According to sources, many of the reports detail González’s frequent visits to Ukraine. Since his arrest, the SBU security services in Kyiv have questioned a number of his local associates and even searched some of their homes. “Over the years, his main task was going to different places near the frontline to collect information about the people working there,” claimed a Ukrainian security source I met recently in a Kyiv cafe. The source told me González had run a local network of politicians and military figures, but the SBU still did not know whether all these people thought they were simply interacting with a journalist, or whether some understood they were helping a Russian intelligence officer. The one thing the SBU is sure of is that a GRU spy with journalistic accreditation could do real damage on the frontline, acting as a spotter to locate concentrations of troops and hardware. “Thank God he was arrested before the full-scale invasion,” said the source.

While the existence of these reports sounds incriminating, it is not clear if Polish investigators possess solid proof that the reports were addressed to the GRU, or that they were ever actually sent. González, under interrogation, apparently claimed they were his own notes. He was not given the chance to defend himself in court: prosecutors only made the indictment official, the key step required for a case to proceed to trial, after he had left the country. Part of the problem may be that under Poland’s espionage law at the time of his arrest, prosecutors had to prove González caused damage to the state of Poland, while most of his alleged spying took place elsewhere. “I think everyone was quite happy when he was included in the exchange and the problem went away,” one Polish former official told me.

The prisoner exchange took place at Ankara airport on 1 August. After leaving the plane that had brought them from Moscow, Yashin and Vladimir Kara-Murza, two of the Russian political prisoners released by Putin, boarded an airport bus that would take them to a German plane, and freedom. From the bus window, the two old friends watched as the group heading in the opposite direction was led across the tarmac to board the plane to Moscow. Suddenly, Kara-Murza nudged Yashin and pointed. “It’s Pablo! Our Basque from Mar’ino,” he exclaimed. Both men knew González well from his days networking in the Russian opposition. Yashin laughed in amazement at the sight.

A few days after the swap, I met Yashin in a Berlin cafe. He was still rather disoriented from his sudden change of surroundings, but told me he wasn’t particularly disturbed by the revelation that his old acquaintance had apparently been a spy. Yashin lived his life expecting to be spied on, so never shared anything privately that he would not say publicly, he claimed. “So Pablo chatted with me, and then wrote a report about me. I don’t think he caused me any harm. Why does the GRU care what kind of coat I’m wearing or what I think about Spanish politics?” The really scary people were those like the Berlin assassin Krasikov, said Yashin. They were sent to liquidate enemies of the Kremlin, not take them to the football.

Without looking into the GRU archives, it is impossible to know just how useful Gonzalez’s alleged spying on the Russian opposition may have been for Moscow. But dismissing it out of hand is probably naive. Writing profiles of targets is a key part of intelligence work. “Profiling tells you how people act, what their views are, what their routines are and what their weaknesses are,” Piotr Krawczyk, the former head of Poland’s foreign intelligence service, told me. Spymasters in Moscow could use the resulting personality profile to craft a recruitment strategy, using either incentives or blackmail. Knowing a target’s daily routines was also crucial, ensuring that the operative sent to make the pitch could be in the right place at the right time. Or, instead of a recruitment officer, the GRU could send someone of Krasikov’s profile, with a gun or a vial of poison.

Some who got close to González have had to deal with a different kind of fallout. The Polish freelance journalist he was dating was arrested together with him, but was soon released after a judge ruled there was insufficient evidence to hold her. In August, however, a Polish media report revealed that there is still a case open against her for abetting espionage. Nothing has come to light that suggests she had any idea what her partner was allegedly up to, but even so, news of the open case led to an online campaign against the woman. Rightwing circles claimed her previous journalism on topics such as abortion rights in Poland was evidence she was a Russian spy following an “anti-Polish” narrative.

Nemtsova, too, is still handling the after-effects of her entanglement with González. For a brief moment, the MA programme her foundation runs at a Prague university was under threat, when a student alleged it had been compromised by Russian intelligence and thus should be discontinued. That challenge is now over; what remains is the psychological trauma of being spied on by someone close to her. “Now I don’t communicate with anyone new, and I have a very limited circle,” Nemtsova told me. “Because I am a target. You cannot live a normal life under these circumstances.”

From Moscow, Pablo González – or Pavel Rubtsov – has logged back into his social media accounts in recent weeks, and is in contact with his lawyer and friends in Spain. Some of these friends initially agreed to speak to me, but later called off the interviews, using variations of the phrase “Pablo wants to tell his own story”. His Spanish wife also declined an interview request, saying: “Pablo is now free and it’s he who will speak with the journalists.”

But so far, the only interview González has given was to Russian state television, a few days after his return to Moscow. In the 10-minute report, he walks the streets of his childhood neighbourhood, pointing out his primary school and other sights from his youth. He scoffs at Poland’s supposed lack of evidence against him and suggests the case is full of holes, though he is never directly asked if he had links to the GRU, and never directly denies it.

González did not respond to multiple requests to speak to me. In a phone call, his Spanish lawyer, Boye, said González has “always denied” all allegations that he worked in any way for Russian intelligence. Boye agreed to forward González my interview requests, and later my specific requests for comment, but González decided not to engage.

For those unconvinced by this denial, the main questions that remain are about what kind of operative González was. Was he really a career illegal, a longstanding officer of the GRU? Polish officials have publicly claimed that González has officer rank in the GRU, and one former security official told me they were certain that González “was recruited at a young age and his whole journalistic career was cover for his spying”. Nobody would say what evidence exists for such claims, however.

For now, an alternative theory seems more plausible: that González was a genuine Spanish journalist with Russian roots, who was then recruited at some point, possibly during his trips to Moscow to visit his father and stepmother. Such an offer would have provided an opportunity to reconnect with the motherland he felt had been torn away from him as a child. It would also have appealed to the risk-taking side of González that so many people noted in him.

Another of the Polish officials I spoke to seemed to lend credence to this theory, diverging from what authorities have stated publicly. In this source’s view, González came across as an amateur: “He was not very professional, he made a lot of mistakes, and you could see that he was quite lazy with his tasks,” he said. “I didn’t get the impression of an incredibly well-trained operative.” If González was recruited at a later stage, it would also help explain the pro-Russian views he espoused to many people, particularly early on in his career. If “Pablo the journalist” was a lifelong cover story created by the GRU, it would surely have been safer to make him less visibly pro-Russian from the start.

The only person who can give the full story is González himself, and for now, a tell-all interview seems unlikely. At the end of his appearance on state television, González talked about his feelings on the night he landed back in Moscow. He did not say he felt alarm about how he might adapt to life in Russia, nor did he express concern at the optics of emerging from a plane full of spies and assassins to a hero’s welcome. Something else was bothering him: “I come out and see that Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin is greeting us – the president! I don’t know if it was visible, but I was training my hand as I was coming down the steps,” said González, grinning. “I wanted to make sure I could give him a decent, strong, manly handshake.”