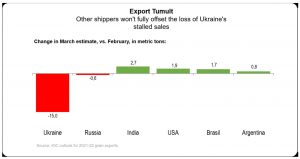

Russia’s war against Ukraine has led to a drop in Ukrainian grain exports, but even shifting supplies from other countries will not be able to compensate for the loss of supplies from Ukraine.

As previously reported by the EP, Ukraine produces a significant share of world food: about 27% of sunflower seeds, 5% of barley, 3% of wheat and rapeseed, 2% of corn. But the country cannot deliver record autumn harvests to the $120 billion world market due to the Russian aggression. Grain exports are currently limited to 500,000 tons per month, compared to 5 million tons before the war. This, according to the Ministry of Agrarian Policy, is a loss of $1.5 billion.

Harvests from Russia, the largest exporter of wheat, although coming, but leave questions about the delivery and payment of future shipments. Especially since the aggressor wants to receive payments in rubles. So, the world’s logistics chains are changing. For example, India, which has historically maintained its huge wheat crops for domestic consumption, is entering the export market and selling record volumes to Asia.

Brazil’s wheat exports in the first three months far exceeded exports over the past year. For the first time in about four years, American corn shipments are headed to Spain. Egypt is considering exchanging its fertilizers for Romanian grain and is negotiating wheat with Argentina. Australia, which is a significant exporter of wheat, has already increased its sales.

Importers, meanwhile, are lifting restrictions on obtaining grain from other sources. Spain, Ukraine’s second-largest buyer of corn, has eased pesticide rules to allow imports from Argentina and Brazil. Importers from North Africa and the Middle East are particularly dependent on Ukrainian and Russian supplies and are trying to find alternatives:

— The International Grains Council estimates that world grain trade, excluding rice, could fall by 12 million tonnes this season, the highest in at least a decade.

— Expanding road, rail and river links between the EU and Ukraine won’t be enough to stave off an economic and humanitarian crisis.

— Ukraine cannot ensure the same volume of exports as via seaports by other means of transportation in forthcoming weeks or even months.

— Some of Ukraine’s cargo has shifted to Izmail, Reni or Kiliya — smaller ports on the bank of the Danube, in the southwest of the country. But those have limited capacity.

— Attempts to squeeze cargo onto freight trains are running into physical barriers, caused by the different gauges used in Western and former Soviet countries, which limit the tracks’ capacity to move Ukrainian cargo into the EU. Thousands of wagons are stuck in queues at the border between Poland and Ukraine.

— The country also wants to ramp up its truck traffic but fears the limited supply of international haulier permits could become a new bottleneck, as it attempts to ship the grain it used to put on ships by road instead.

— The logistical challenge is immense. Before the war, Ukraine shipped over 70 percent of its exports. In 2021, 99 percent of Ukraine’s 24.6 million tons of corn exports were shipped out.

— Russia’s blockage of Ukraine’s seaports “is not only a threat, it’s a direct increase of hunger in the world by different means.

Unblocking Ukraine’s seaports is the only solution to country’s trade crisis.