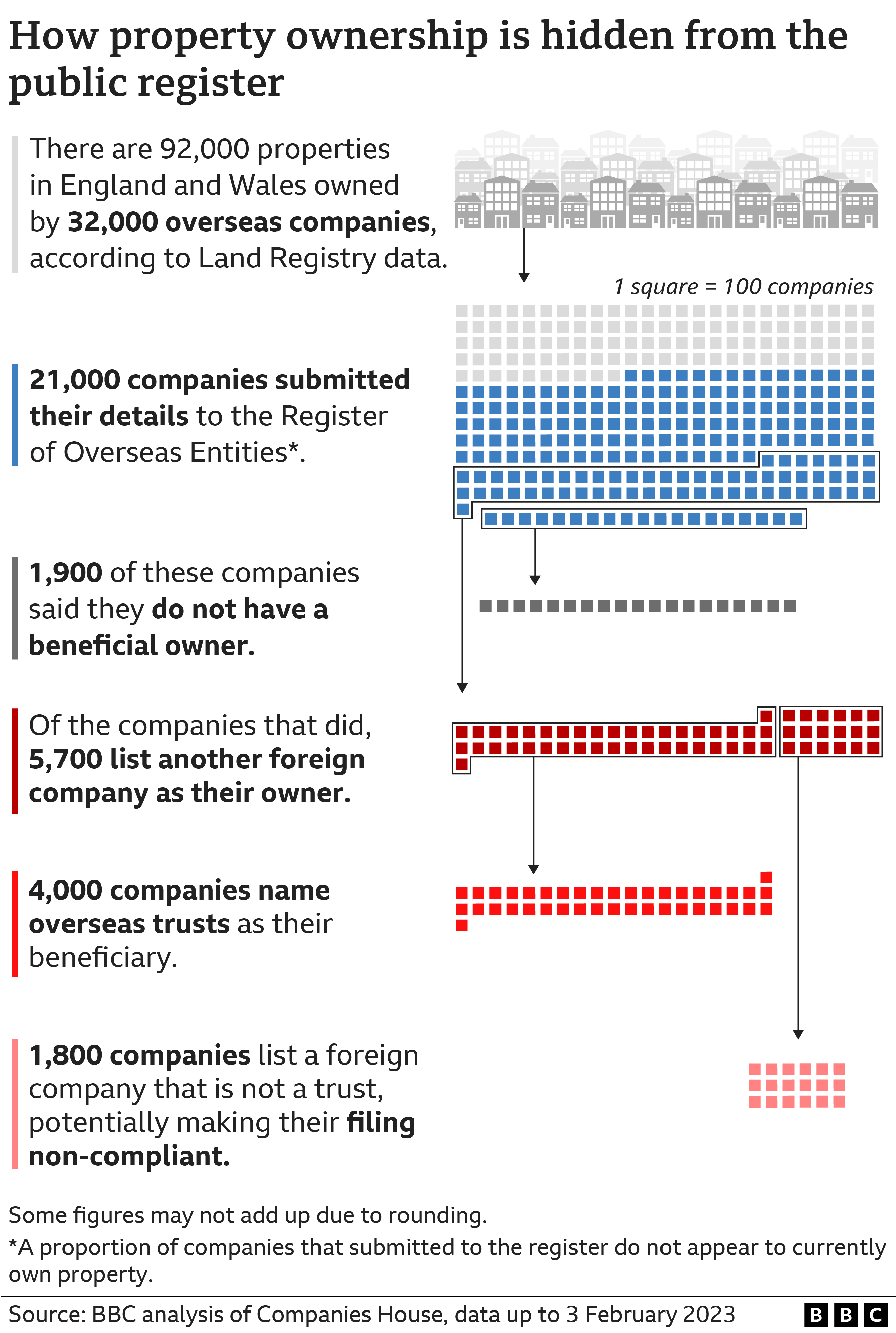

Owners of around 50,000 UK properties held by foreign companies remain hidden from public view, despite new transparency laws, reports BBC News.

The Register of Overseas Entities, launched in August 2022, was meant to reveal who ultimately owns UK property.

But analysis by BBC News and Transparency International found almost half of firms required to declare who is behind them failed to do so.

Labour MP Margaret Hodge said the legislation was not «fit for purpose».

A UK government spokesperson said the register has been an «invaluable source of information for law enforcement, and tax and revenue services».

The UK government has long promised to crack down on «corrupt elites» from overseas, including «Russian oligarchs and kleptocrats», using UK property to launder illegal wealth.

Ministers insisted they would crack down on foreign criminals using UK property to launder money by ensuring they «can’t hide behind secretive chains of shell companies».

As a result, under a law passed in February 2022 in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, ministers said anonymous foreign companies seeking to buy UK land or property would be required to reveal full details of the individuals who ultimately owned them. Overseas organisations that already owned land in the UK were given a six-month period to do the same.

Now that six-month grace period is up — all the people, whatever their reputations, behind companies that own thousands of British properties should have been uncovered for the first time.

The BBC and Transparency International matched thousands of filings from the new register with Land Registry records. This analysis suggests that some 18,000 offshore companies — which between them hold more than 50,000 properties in England and Wales — either ignored the law altogether or filed information in such a way that it remains impossible for the public to find out who the individuals are who ultimately own and benefit from them.

«While the register is starting to serve its intended purpose, our analysis reveals there are far too many companies that could be trying to skirt the rules, not knowing they exist, or ignoring them altogether,» says Duncan Hames, Director of Policy at Transparency International UK.

To understand how the law is and isn’t working, it helps to look at three very expensive properties. The first is a pair of luxury apartments. Another is a sprawling £48m estate in north London, the third a £10m country mansion.

All have been linked in some way to figures connected with Vladimir Putin’s regime.

For instance, look at the two luxury flats in central London worth an estimated £11m.

Their ownership by the former Russian deputy prime minister, Igor Shuvalov, was first reported by the Anti-Corruption Foundation, set up by jailed Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

According to the UK government, who placed him under sanction in March 2022, Mr Shuvalov — who heads the management board of a Russian bank — is «a core part of Putin’s inner circle».

And now the register has confirmed that he and his wife are the ultimate owners of the flats, held through a Russian company, Sova Real Estate LLC.

Mr Shuvalov’s spokesperson told the BBC last year that these issues «have been the subject of competent government audits», and that «no complaints were ever filed».

But while there are thousands of examples where the register is working, the ultimate ownership of thousands of properties remains shielded from public view.

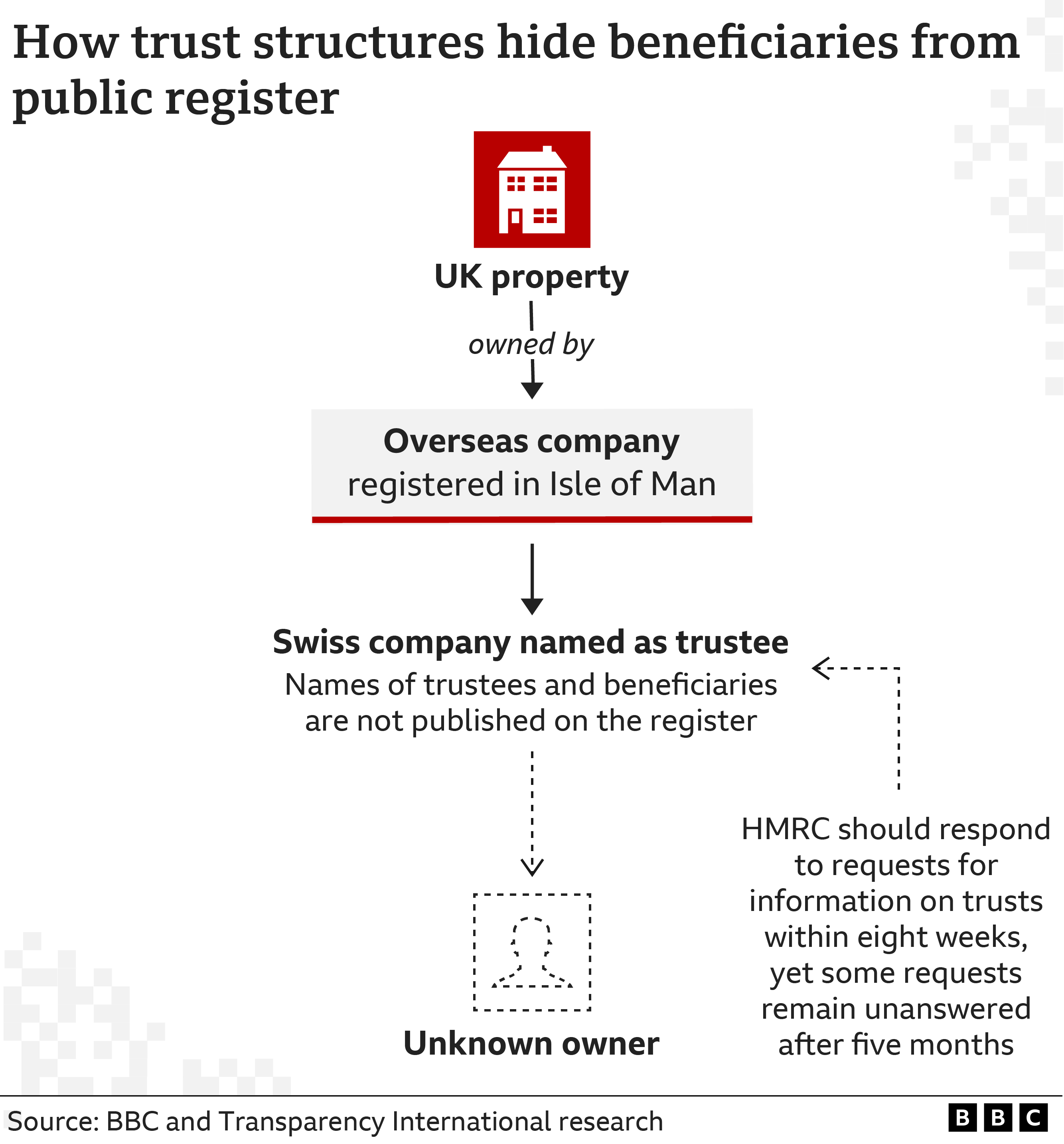

Take Beechwood House, a north London estate bought for £48m in 2008 with a value around £85m.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine 12 months ago, the UK government came down hard on wealthy businessmen close to Putin’s regime. Assets were frozen, stopping rich Russians from taking their money out of the UK.

But it wasn’t always clear exactly which assets belonged to these oligarchs.

For instance, Beechwood House was listed by the government as owned by oligarch and ex-Arsenal shareholder Alisher Usmanov when it announced sanctions against him.

A spokesperson for the oligarch has now told the BBC that he transferred Beechwood House, as well as other assets, to family trusts «long before sanctions were imposed» and that while Mr Usmanov was a beneficiary for a period of time, he withdrew «on an irrevocable basis».

The spokesperson added: «Neither Mr Usmanov nor members of his family are the beneficial owners of these companies.»

You would think the register should shed light on who actually owns Beechwood House. But it does not.

The owner is given as Hanley Limited, an Isle of Man company. And in turn the beneficial owner of Hanley Limited is Swiss company Pomerol Capital SA, which controls it as part of a trust structure.

However, nothing about the individuals who own Pomerol Capital is listed on the public register.

That is because companies owned through trusts — as opposed to other set-ups — are exempt from having their beneficial owner information made public on the register.

So from the filing, it is impossible to identify the people who own, control or stand to benefit from Beechwood House- a property that the government itself said was owned by Mr Usmanov, which would have made it subject to an asset freeze.

While the names of individuals linked to trusts are not included in the register, companies do have to provide their details privately to the corporate registry Companies House.

And many other owners have found an even more straightforward means of keeping their names off the register — by simply not complying with the new legislation.

Overseas companies with property in the UK — bought since January 1999 in England and Wales and since December 2014 in Scotland — were supposed to reveal the identity of their owners by 31 January.

But around half of offshore firms with property in England and Wales — approximately 15,000 — had no matching record in the property register before last week’s government deadline.

This includes the company that owns a £90m home in west London linked with former Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich. The Cyprus-based firm does not yet appear to have submitted its details to the property register.

Mr Abramovich could not be reached for comment.

As well as the firms that are yet to file, BBC analysis has found that one in four offshore companies that have submitted their details have actually included other foreign firms, not people, as their owners.

Some of these are owned by trusts, as with Beechwood House.

But that is not the only way in which companies are avoiding publicly disclosing the individuals who are actually behind them.

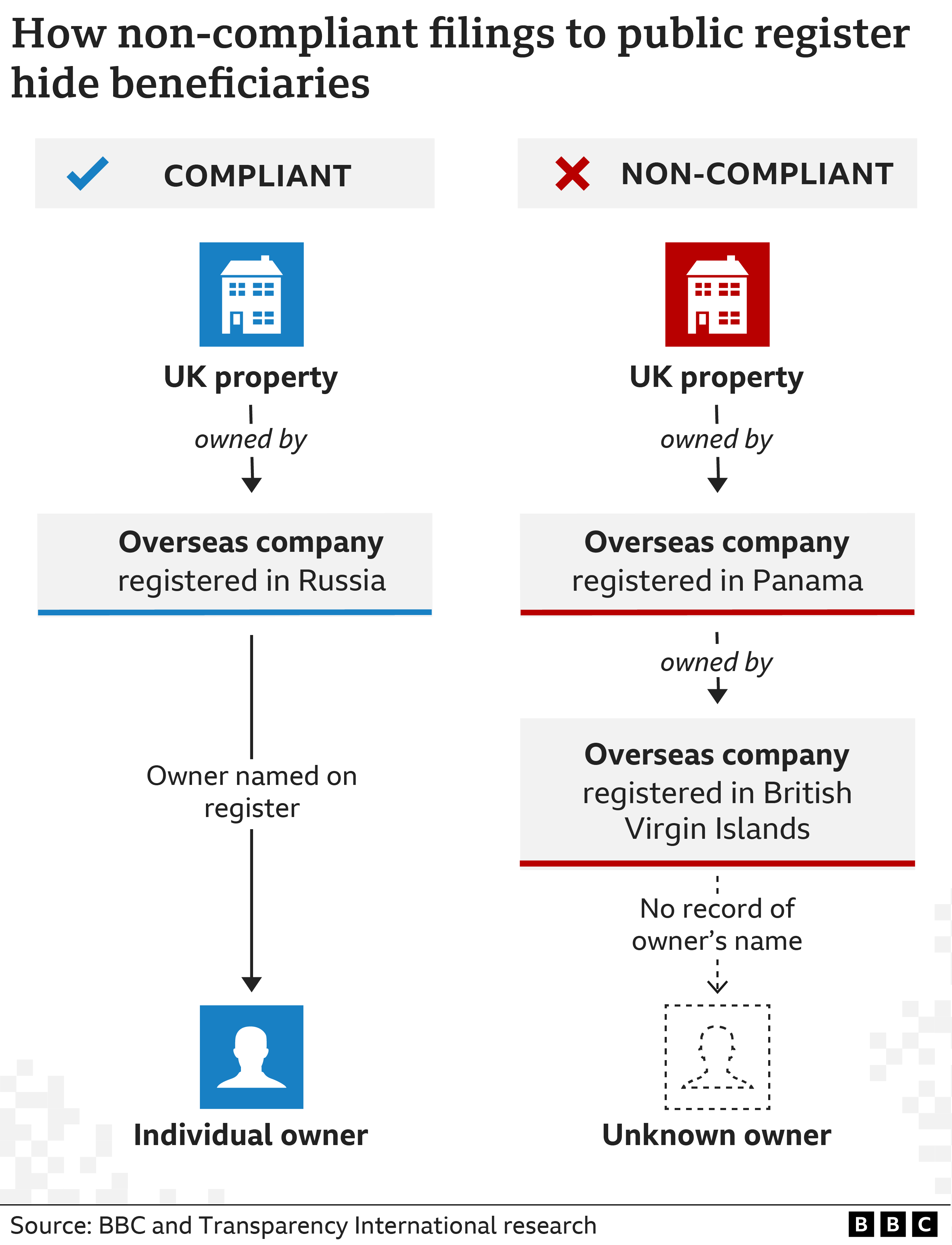

And there is a third category — companies that have filed their details to the property register, but have not complied with the rules.

The BBC’s investigation has identified more than 1,800 companies whose filings do not appear to do so.

Among these is Uart International, a Panamanian company that, according to Land Registry records, acquired a countryside mansion in 2008.

As part of the Pandora Papers, a leak of almost 12 million files, the property was owned through an offshore corporate network controlled by Vladimir Chernukhin and his wife, Lubov.

Mr Chernukhin is a former Russian deputy minister of finance and businessman who had financial links to oligarchs close to the Kremlin. He moved to the UK after being sacked by Putin in 2004 and insists he is not a supporter of the Russian president.

His wife Lubov, whom he married in London in 2007, is a major donor to the Conservative Party, having given the Tories more than £2.3m since 2012.

Companies House records show that Uart International lists another foreign firm as its «person of significant control». This means that the individuals who ultimately own the property remain hidden from the public register, despite the change in the legislation.

Under the new regulations, another anonymous offshore firm should not be named as the owner of a company with UK property.

There is no indication in the filings that the company owner is a trustee, which would exempt the firm from having their person of significant control revealed on the register — suggesting it could be a violation of the rules.

Lawyers for the couple told the BBC that «Mr and Mrs Chernukhin do not support, and have never supported, the policies of President Putin, nor are they allies of President Putin» and that they are «unaware of Uart ever having made corporate filings contrary to the applicable rules and regulations in all relevant jurisdictions».

While the new rules include severe penalties for companies and individuals who do not comply, experts have questioned whether this will work.

«Although the legislation contains some stringent penalties for non-compliance, the government has failed to equip Companies House with the teeth and resources to apply these in practice,» says Helena Wood, head of the UK Economic Crime Programme at the Royal United Services Institute think tank.

Margaret Hodge MP, chair of the all-party parliamentary group on anti-corruption and responsible tax, said the new register was «turning into a joke».

She added: «We need to know who owns these fantastically expensive properties, why they bought them and how they got the money to do so.»

A government spokesperson said that Companies House was now «assessing and preparing cases for enforcement action» and further legislation would allow it to impose fines and pursue legal avenues against companies that are flouting the law.