One year of war in Ukraine has left deep scars — including on the country’s natural landscape. The conflict has ruined vast swaths of farmland, burned down forests and destroyed national parks. Damage to industrial facilities has caused heavy air, water and soil pollution, exposing residents to toxic chemicals and contaminated water. Regular shelling around the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, the largest in Europe, means the risk of a nuclear accident still looms large.

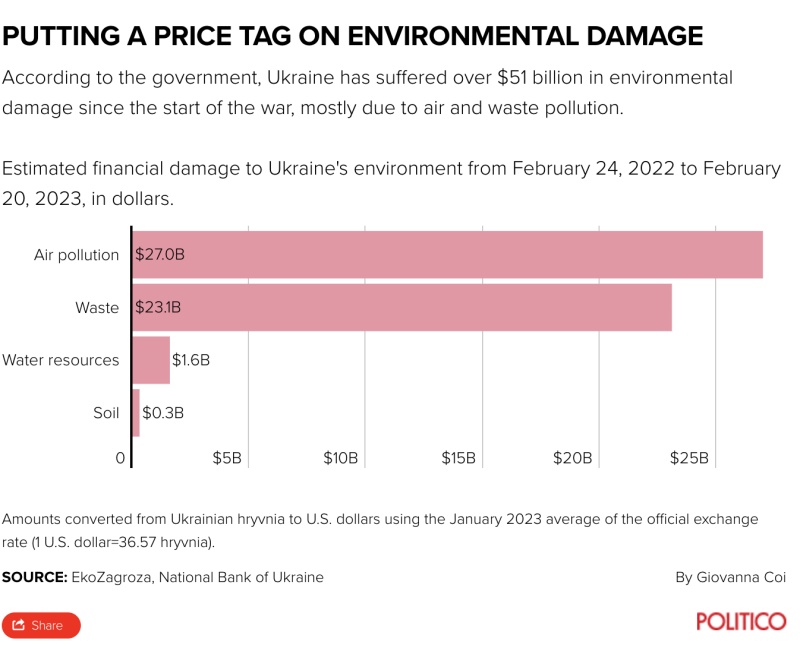

The total number of cases of environmental damage tops 2,300, Ukraine’s environment minister, Ruslan Strilets, told POLITICO in an emailed statement. His ministry estimates the total cost at $51.45 billion (€48.33 billion).

Of those documented cases, 1,078 have already been handed over to law enforcement agencies, according to Strilets, as part of an effort to hold Moscow accountable in court for environmental damage.

A number of NGOs have also stepped in to document the environmental impacts of the conflict, with the aim of providing data to international organizations like the United Nations Environment Program to help them prioritize inspections or pinpoint areas at higher risk of pollution.

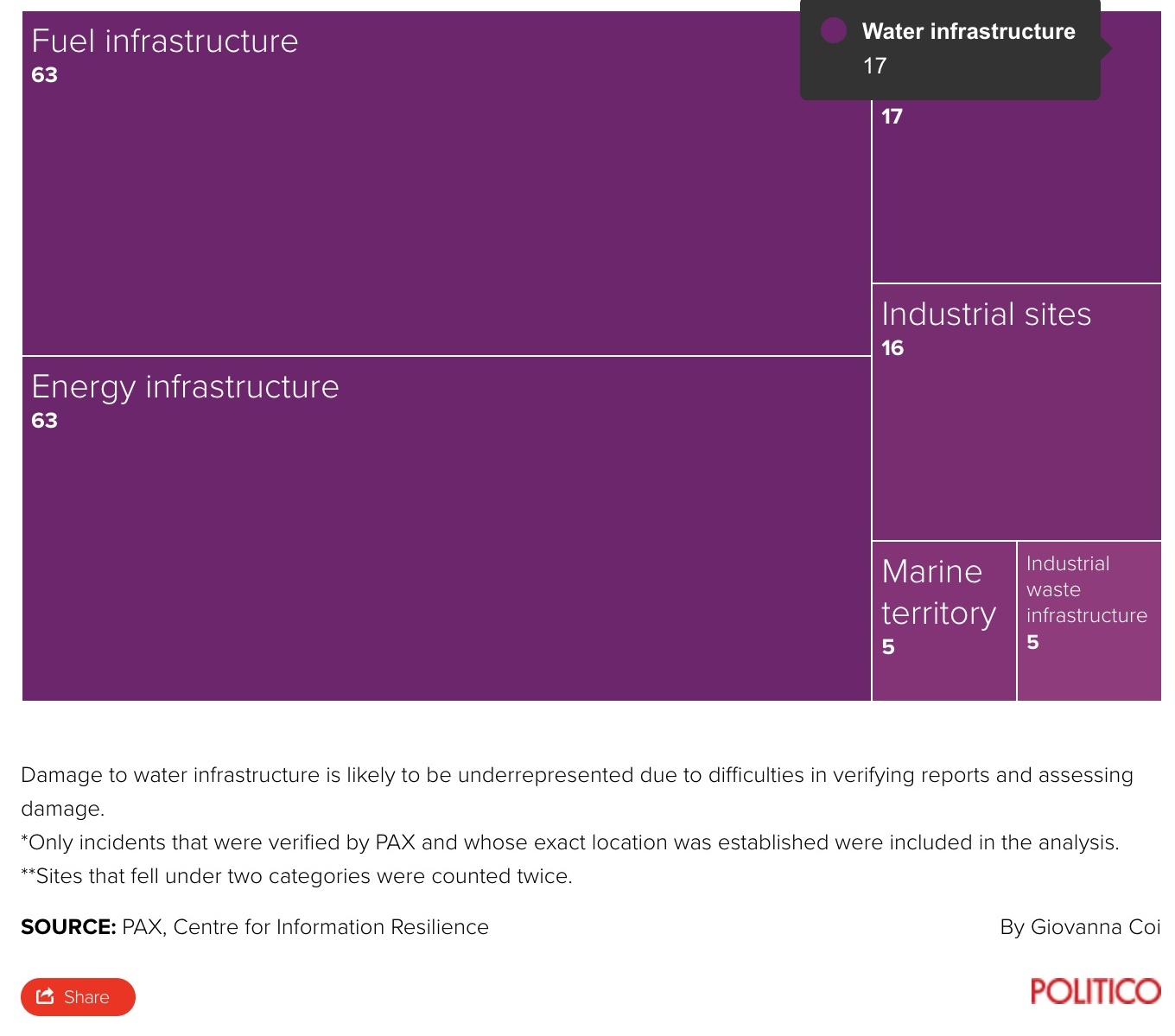

Among them is PAX, a peace organization based in the Netherlands, which is working with the Center for Information Resilience (CIR) to record and independently verify incidents of environmental damage in Ukraine. So far, it has verified 242 such cases.

Left: Hostomel, Ukraine, after a Russian assault. Right: Port of Mykolaiv after a Russian strike | Imagery courtesy of Planet Labs PBC

“We mainly rely on what’s being documented, and what we can see,” said Wim Zwijnenburg, a humanitarian disarmament project leader with PAX. Information comes from social media, public media accounts and satellite imagery, and is then independently verified.

“That also means that if there’s no one there to record it … we’re not seeing it,” he said. “It’s such a big country, so there’s fighting in so many locations, and undoubtedly, we are missing things.”

After the conflict is over, the data could also help identify “what is needed in terms of cleanup, remediation and restoration of affected areas,” Zwijnenburg said.

Rebuilding green

While some conservation projects — such as rewilding of the Danube delta — have continued despite the war, most environmental protection work has halted.

“It is very difficult to talk about saving other species if the people who are supposed to do it are in danger,” said Oksana Omelchuk, environmental expert with the Ukrainian NGO EcoAction.

That’s unlikely to change in the near future, she added, pointing out that the environment is littered with mines.

Agricultural land is particularly affected, blocking farmers from using fields and contaminating the soil, according to Zwijnenburg. That “might have an impact on food security” in the long run, he said.

When it comes to de-mining efforts, residential areas will receive higher priority, meaning it could take a long time to make natural areas safe again.

The delay will “[hinder] the implementation of any projects for the restoration and conservation of species,” according to Omelchuk.

And, of course, fully restoring Ukraine’s nature won’t be possible until “Russian troops leave the territory” she said.

Meanwhile, Kyiv is banking that the legal case it is building against Moscow will become a potential source of financing for rebuilding the country and bringing its scarred landscape and ecosystems back to health.

It is also tapping into EU coffers. In a move intended to help the country restore its environment following Russia’s invasion, Ukraine in June became the first non-EU country to join the LIFE program, the EU’s funding instrument for environment and climate.

Earlier this month, Environment Commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius announced a €7 million scheme — dubbed the Phoenix Initiative — to help Ukrainian cities rebuild greener and to connect Ukrainian cities with EU counterparts that can share expertise on achieving climate neutrality.